Greece is one of the few countries in Europe today that openly embraces the Israeli army, holding joint military exercises with Israel and acting as an enthusiastic partner for Israeli arms and surveillance companies. Against the background of Israel’s current constitutional and political crisis, Greece has also reportedly been trying to attract more Israeli hi-tech companies, many of which build military or dual-use products, by offering them extremely generous incentives.

This close relationship has also had a major impact on Greek domestic politics. Last year, for example, it was revealed that an Israeli former intelligence general named Tal Dilian, who runs a spyware company from an office in Athens, was involved in a political and legal scandal over the spyware’s use against Greek politicians and journalists; both the head of intelligence and the adviser to the prime minister of Greece were forced to resign.

How did this unique relationship form? Publicly, Israel and Greece trace their strong ties back only to 1990, when full diplomatic relations were established and an Israeli embassy opened in Athens. On May 21, 2015, the 25th anniversary of that milestone, the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs published a celebratory statement explaining its narrative of Greek-Israeli diplomacy, according to which the period between 1952 and 1990 saw only low-level relations between the two countries.

In recent years, the statement continues, “a strategic partnership has developed between the two countries … based on democratic values and common interests shared by the two countries, which face challenges in the Eastern Mediterranean region … The two countries, Greece and Israel, are modern and democratic scions of ancient nations … The bilateral cooperation between the two countries promotes common values, progress and stability in the region. Both countries strive to continue to promote peaceful and good neighborly relations with peoples and nations in the region.”

This account of the military relations between Israel and Greece is, however, untrue. Telegrams in the files of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the Israel State Archives, which were opened to the public between 2019-2020, show that the two countries’ special relationship was in fact born much earlier than 1990, and had nothing to do with the “democratic values” of either Greece or Israel. The relationship blossomed during the dark days of the military junta that ruled Greece from 1967 and 1974 — a period marked by the brutal repression, imprisonment, torture, and murder of opponents of the regime, and a period that was deliberately omitted from the celebratory narrative Israel promotes.

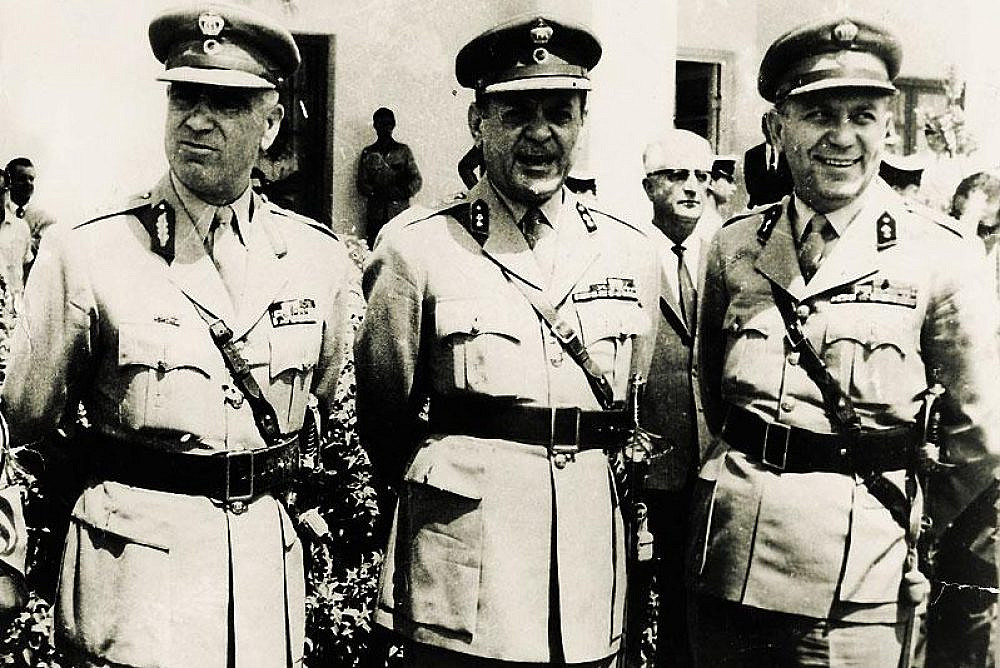

Before the junta came to power, Greece’s relations with Israel were cold: it preferred to build diplomatic and economic ties with Arab countries, and even voted against the 1947 UN Partition Plan. Then, under the pretext of dealing with the “communist threat,” a group of generals staged a military coup in Greece in April 1967. Immediately upon seizing power, the military junta began a campaign to eliminate its real and imagined opponents, an effort embraced or tacitly supported by most Western European countries and the United States.

Although there is disagreement regarding the exact number of victims of the junta, several thousand activists, students, artists, writers, actors, journalists, and even World War II veterans were arrested, subjected to severe torture, and murdered. Some were held in detention and torture camps for many years, with little food and water and no medical treatment. The torture practices included whipping the feet with sticks and plastic tubes, inserting a tube into the detainee’s body and pouring water inside, banging the head against the wall or the floor, the torturers jumping on the detainee’s stomach, pulling out nails, causing burns and extinguishing cigarettes on the body, electrocution, and even sexual torture.

Although most of the files and documents of Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs remain classified, the telegrams in the archives that have been made available to the public reveal that Israel was well aware of these human rights violations and nevertheless continued its close military and political ties with the military junta and even considered it more friendly to Israel than the civilian regimes that preceded it. And yet, cognizant of diplomatic optics, Israel sought to hide the nature of its relations with Greece — a practice that continues to this day.

Establishing the relationship

A telegram sent by the head of the Israeli mission in Athens, Yehoshua Nissim Shai, only two months after the coup, demonstrates Israel’s awareness of the political repression in Greece at the time. In June 1967, Shai complained that it was not possible to carry out Israeli PR activities in Greece because the locals were afraid to engage in any political matters: “It is … absolutely forbidden for an individual to engage in political matters in the severe military regime that prevails in this country … It is enough for a person to express any political opinion without the approval of the authorities for him to find himself arrested the next day.”

Despite Shai’s awareness of these political crimes and apparent personal discomfort with them, a series of communications and meetings that took place in the immediate aftermath of the junta’s coup are indicative of the quickly warming relations between the two countries.

Less than one month after sending the telegram, Shai reported in another telegram on his meeting with the junta’s foreign minister and his effort to motivate the junta to take a more sympathetic and understanding stance toward Israel. The foreign minister responded that the junta, and even he personally, had a very positive attitude toward Israel and “is happy about the glorious victory of the IDF” in the 1967 war, which had ended just a few weeks earlier. According to the minister, because of the junta’s diplomatic interests in the Arab world, he could not take a public pro-Israel line as he wanted, but he promised to do everything possible to soften the position of the Greek representative at the UN toward Israel.

In another telegram describing a subsequent meeting with General Nikolaos Makarezos, one of the leaders of the coup, Shai reported: “The conversation revolved around his visit to Israel at the beginning of this year. The minister mentioned his contacts with Mossad personnel and spoke highly of Israel’s achievements.”

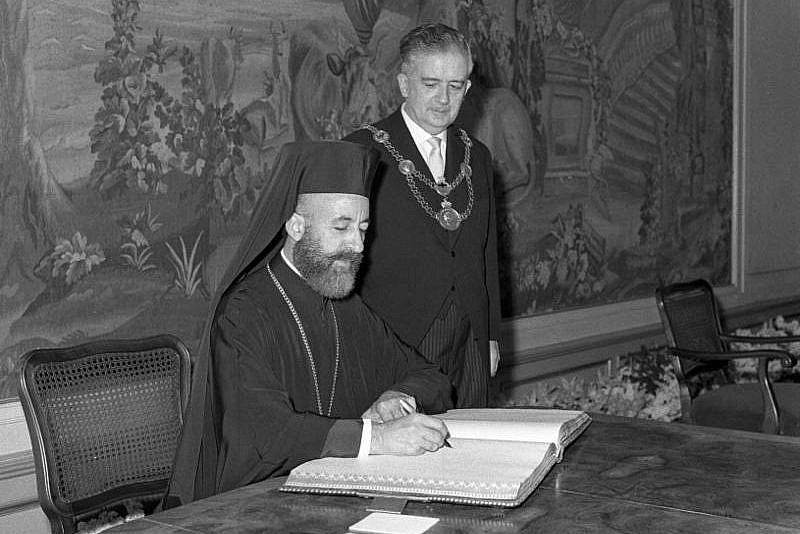

On Sept. 17, the relationship developed further. The deputy speaker of the Knesset at the time, Yitzhak Navon, visited Greece and met with Constantine Kollias, the prime minister appointed by the military junta. According to the summary of the meeting, Navon tried to convince Kollias to vote with Israel in international forums such as the United Nations. Kollias expressed appreciation and admiration for the State of Israel, saying that he saw Greece and Israel as fighting “against the common enemy — communism” and added that “your hopes [are] our hopes.” Kollias later explained that he was upset with “attacks … in the press by Jews on the Greek government and police.”

Instead of calling out Kollias’s complaint for being tinged with the antisemitic trope that Jews control the media, Navon tacitly validated his concern and said, “The government of Israel has no control over the press in the world, not even in Israel itself. But it is possible to ‘soften’ this attitude in certain cases. Greece’s support for Israel may bring it sympathy in the free world.”

A market for modern and cheap weapons

A year later, the nascent diplomatic ties between Greece and Israel crossed over into military cooperation. In October 1968, Yaakov Ben-Sher, Israel’s commercial attaché in Greece, wrote that he met with Makarezos to discuss a visit by a delegation of Greek military officers to Israeli Military Industries, the state-owned weapons manufacturer, at Israel’s invitation. It was agreed that the delegation would not arrive in uniform and that the visit would not be publicized. The next month, Ben-Sher wrote that among the goals of the visit were “establishing a maintenance plant for aircraft in Greece, Israel Aerospace Industries, [and] the presentation of weapons and military equipment produced in Israel.”

The junta’s air force delegation visited Israel between Nov. 25 and Dec. 3, 1968. A report prepared by the Greek delegation after the trip outlined their activities in Israel: the group visited Israeli Military Industries’ factory; was interested in Uzi submachine guns, lighting bombs, and smoke grenades; and discussed the possibility of Israel maintaining the junta’s air force aircrafts, and even Israeli assistance in the establishment of an arms manufacturing industry in Greece.

The Greek military delegation wrote that “due to the constant development of the Greek army and due to the reduction of the U.S. military aid program, Greece is dependent on the international arms markets, since the supply of the necessary equipment and weapons would not be immediately resolved by establishing a national arms industry. From this perspective, Israel is a market for modern and cheap weapons and is a site for extensive commercial exchanges and close economic cooperation for the benefit of both sides.”

On Jan. 30, 1969, Ben-Sher reported that he met again with the junta’s minister of coordination, Makarezos, and talked with him about the purchase of Gabriel missiles, land army communication equipment from Tadiran (an Israeli company), and even Israeli assistance in building a nuclear reactor in Greece. According to a telegram from June 5, 1969, sent by the Israeli mission in Athens, the chairman of the Greek Atomic Energy Commission visited Israel during the previous month, but it is not clear from Israeli Foreign Ministry documents disclosed to the public if and how Israel aided Greece’s nuclear development.

‘The rulers of today will also be the rulers of tomorrow’

As diplomatic relations between the State of Israel and the junta tightened, so did their economic ties. On Feb. 8, 1969, a new commercial agreement was signed, revealing the inextricable link between each country’s military and economy. In a telling symbol of the increasingly close ties, Yaakov Cruz, the former deputy head of the Mossad, was appointed to the position of head of the Israeli mission in Athens in early 1968.

During May 1969, preparations began for a visit to Greece by an Israeli economic delegation, including representatives of the arms manufacturers. For reasons of political sensitivity, Israel decided to downgrade the level of participants in, and the visibility of, the delegation. In response, Cruz sent a telegram to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in which he tried to reverse the decision to downgrade. “Our relations with the current government have improved a lot compared to our relations with its predecessors,” wrote Cruz.

“Many of the Greek exiles were our most prominent opponents when they were in power, led by Andreas Papandreou,” he continued. “All Western countries, without exception, make great efforts, and often without limits, to succeed in as many economic transactions as possible with Greece, including the supply of military equipment.” Cruz concluded his telegram by writing that, in his opinion, Israel should not be ashamed of its relations with the junta, since it was equally clear to all Western countries, and in particular to the USA, that the “the rulers of today will also be the rulers of tomorrow.”

On May 16, 1969, Cruz reported on a meeting he and the CEO of Israel Aerospace Industries, Al Schwimmer, held with the head of the military junta in order to “present the possibilities and proposals of Israel Aerospace Industries.” Cruz wrote that he reviewed with the head of the junta the progress that had taken place since his last visit: “Three agreements have been signed between us, two military delegations have already visited, and a third will leave next week to Israel. A goodwill delegation to promote economic ties is about to come to Greece at the beginning of June, and the visit of the CEO of Israel Aerospace Industries is also part of the effort to develop these ties.” The head of the junta thanked Cruz for the explanations he received and emphasized the need for cooperation between the two countries.

Keeping it a secret

At the beginning of June 1969, another Israeli economic delegation visited Greece. In several telegrams around that time, Cruz wrote that the members of the Israeli delegation received important proposals such as “establishing a maintenance plant for aircrafts, overhauling aircrafts’ engines and selling weapons”; that the delegation met with the Greek military’s chief of staff, the junta’s officers, and other senior officials; and that the Israeli company Tadiran had signed a deal with the regime worth $2 million.

In a telegram sent by economic attaché Ben-Sher on Oct. 30 of the same year, he wrote that “the Greek army ordered communication equipment from Tadiran in the amount of $2,316,500. The order was finally approved by the Israeli prime minister and the minister of defense. The contract will be signed within a week to 10 days. The contract is to be executed in 1970.”

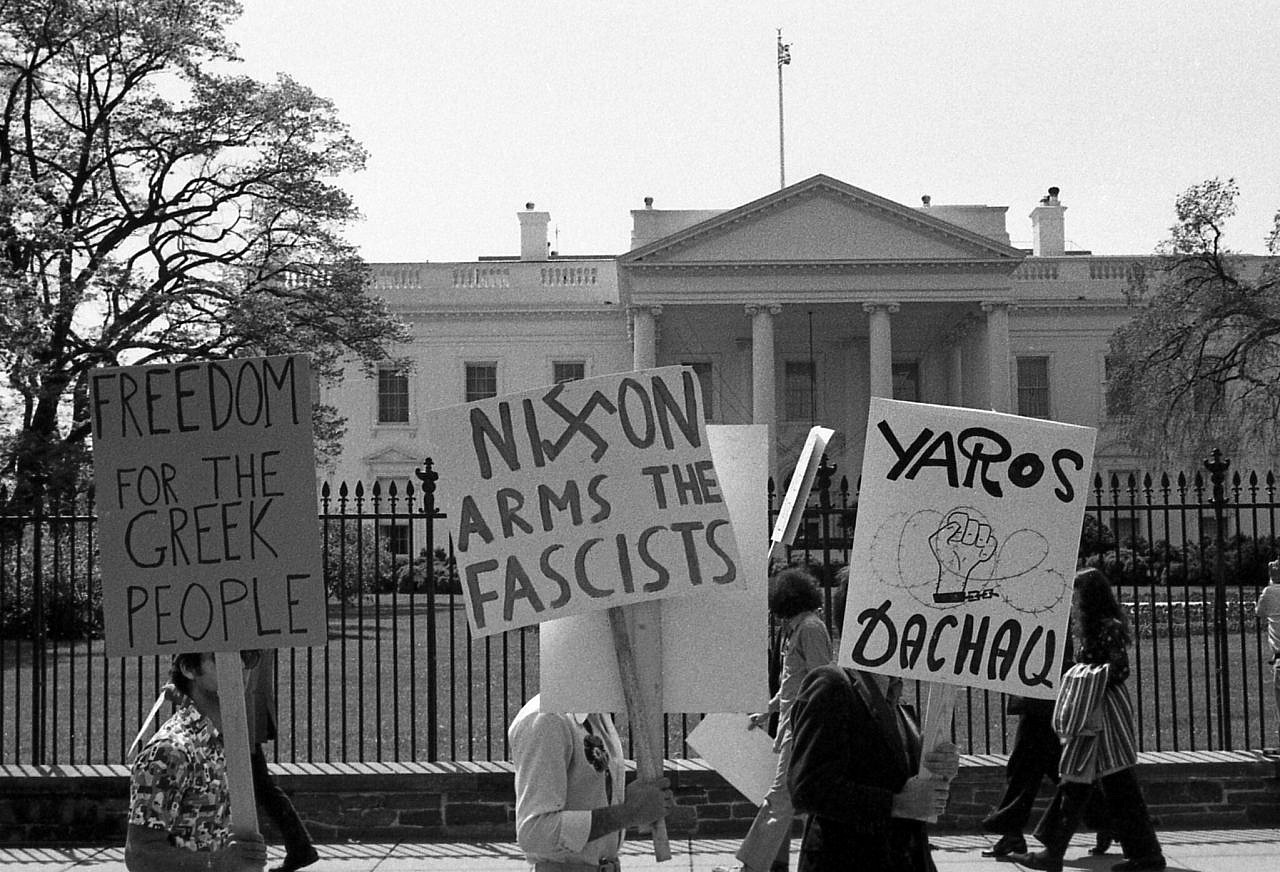

The close relations with a military junta that had become infamous for its human rights violations raised some concerns, however. “In my conversations with various people, they expressed their regret at the publicizing of the strengthening of our ties with Greece during this particular period,” the deputy head of the Israeli delegation in Brussels wrote to the director of the European division at the foreign ministry in 1969. “Last night, two friends told me that they understand the need for realpolitik in the special situation that Israel is in, and especially in what concerns our economic relations, but they wondered if it is not possible to prevent, or at least to moderate, the publicizing of this matter.”

In a telegram sent by the head of the office of the director general of the Foreign Ministry, Hanan Bar-On, to the leadership of the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs a short time later, he asked to “try as much as possible to be modest in publicizing the progress of our practical relations with Greece, be they in commerce or in other areas.” In accordance with this request, the members of the junta’s air force delegation, who visited Israel for negotiations on the renovation and maintenance of aircrafts, arrived in civilian clothes.

According to a report prepared by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1972, Israel sold parachutes worth approximately $250,000 to the Greek military, and they conducted negotiations regarding the sale of searchlights to the Air Force and the Armored Corps. But the junta wanted more. “The Greek army is interested in buying other military equipment in Israel, but we do not have political approval for this,” Dr. Yitzhak Azouri, an Israeli diplomat stationed in Greece, wrote in 1972, “for example, rockets.”

The following year, Israel went so far as to assist Greece in one of the most sensitive areas of Israeli international relations. On Jan. 17, 1973, Azouri reported that an agreement was signed with the junta to transport crude oil from the Persian Gulf through the Eilat-Ashkelon oil pipeline, and from there on to Piraeus, Greece. “A transport of about 250,000 tons (in the amount of about $1.5 million) has already been carried out,” Azouri reported. “It was agreed in principle to transport around 1.5 million tons, that is, in the amount of about $9 million.”

Azouri was reprimanded for his reports on a sensitive issue like oil. “In your review of Israel-Greece economic relations, you mentioned the matter of the oil pipeline, which is considered a top secret issue,” he was told in a telegram sent by the economic department of the Foreign Ministry on April 6 of that year. “Please inform the recipients about the secret classification of the telegram.”

Undeterred by escalating brutality

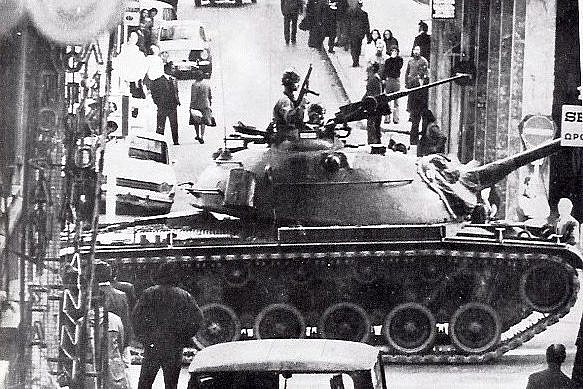

As its relations with Israel grew increasingly warm, Greece was becoming ever more oppressive inside its borders. On Nov. 17, 1973, in response to a student strike, junta forces raided the premises of the National Technical University of Athens with tanks, killing dozens of civilians. Although news of the atrocity was reported all over the world, including in Israeli newspapers, the State of Israel did not waver in its support of the junta or take a step back in its economic relationship.

On March 12, 1974, Azouri reported that “according to the estimate, the payments of Greece for transporting crude oil from the Persian Gulf through the oil pipeline will amount to about $8 million.” According to the same report, two Greek military delegations visited Israel in 1973, with the junta’s air force signing an arms deal with Israel Aerospace Industries for hundreds of weapons and other military technology, including 466 units of Uzi submachine guns, worth well over $1 million, with other deals in the works worth millions more.

Azouri also noted that after a visit to Israel by the Greek Air Force delegation, the Greeks decided to purchase bombs from Israel, subject to budgetary approval. Israel won a tender worth approximately $750,000 for the supply of 81 mm mortars, submitted proposals for the supply of hand grenades and the establishment of a factory for the production of hand grenades in Greece, and Tadiran signed an agreement for the supply of communications equipment worth $300,000.

Azouri did not raise the possibility of canceling or freezing these deals in light of the massacre in Athens and other human rights violations. It seems, in fact, that Israel doubled down on its military relations with Greece: Azouri, alongside another Israeli diplomat named Yael Vered, negotiated a deal in which the junta’s air force decided to purchase bombs and aircraft armament accessories worth $4–5 million dollars. It was also agreed that within a month bomb models would be transferred to the junta for testing in their planes, pending budgetary approval.

At the time these deals were being negotiated, the junta was involved in the violent destabilization of Cyprus and supported the Greek nationalists who wanted the island to be annexed to Greece –– in opposition to the wishes of the elected government in Cyprus and the Turkish minority on the island. According to documents from the Israeli Foreign Ministry, Israel was aware that the junta was transferring military equipment to the forces it had stationed illegally on Cypriot soil. For example, in discussing one of the recent arms deals between Greece and Israel, Azouri said: “The problem is more political, as some of the mortars are intended for the Greek army in Cyprus.”

His solution to the bad optics was to propose handing over the mortars without marking, and he added that the Foreign Ministry “has no objection to the Greek army in Cyprus receiving the mortars, and over time this can be brought to the attention of [Cypriot President and Archbishop] Makarios III, who has an interest in the Greek army’s activities on the island.”

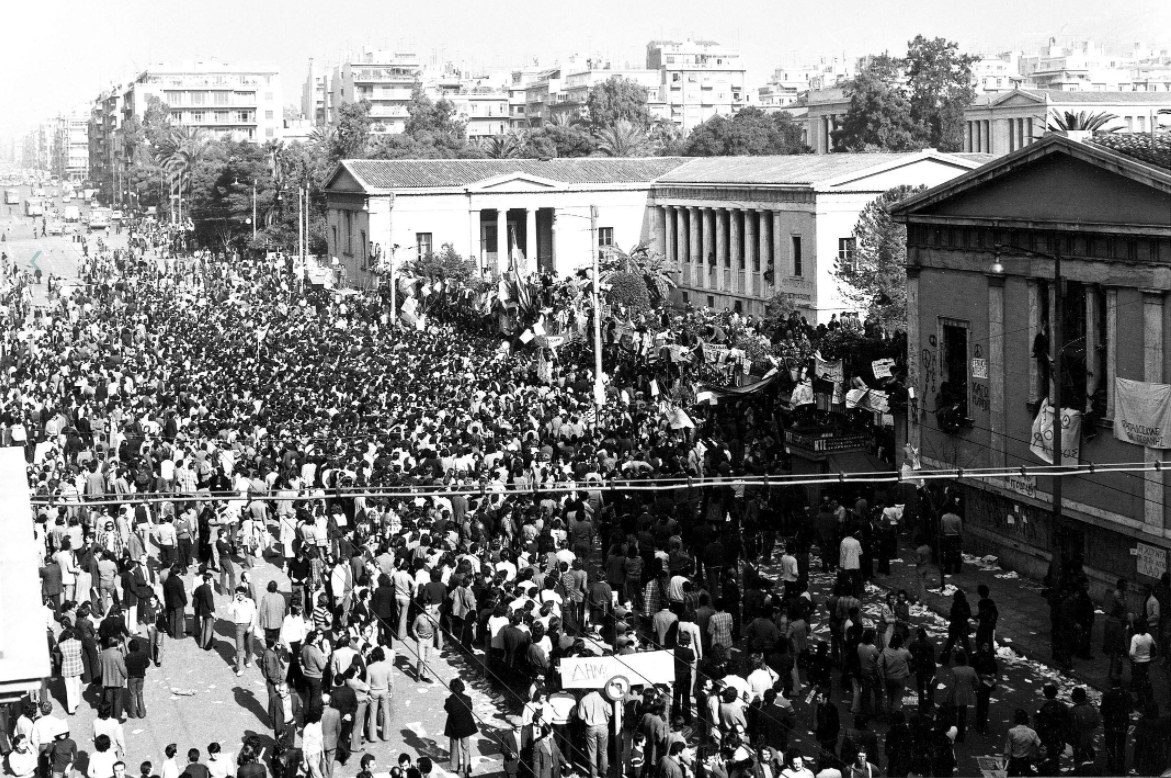

Learning the wrong lessons

It was the junta’s intervention in Cyprus — supporting a military coup that took place on July 15, 1974 — that ultimately led to its downfall. The leaders of the coup deposed Makarios, and announced their intention to annex the island to Greece. Five days later, Turkey invaded the island in the name of protecting its Turkish minority and occupied the northeast. Two hundred thousand Greek Cypriots living in this area were deported or fled from the Turks, leading the island to be divided along ethnic lines, which has lasted to this day.

Israel was well aware of the junta’s involvement in what was happening. According to a situation assessment prepared by the Israeli ambassador in Nicosia on July 18, three days after the military coup on the island: “There is no dispute that the coup was carried out by the Greek officers of the Cypriot National Guard, in accordance with instructions from Athens. The assessment is that the ruling sect in Athens acted out of a lack of understanding of international affairs and from a provincial perspective.”

On July 22, a week after the coup, the exiled president of Cyprus, Makarios, asked Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin for assistance in preserving the island’s independence. Instead of providing aid, however, the Rabin government simply decided to send Makarios a nonchalant greeting from the former Israeli ambassador to the island, Rachamim Timur, in which he hoped for his well-being, wishing him health and all the best. Rage at the military junta’s intervention in Cyprus led to its collapse, and Greece began the process of becoming a democracy once again.

Yael Vered, the Israeli diplomat, prepared a summary of the lessons to be learned from the recent Cyprus crisis. “Israeli conclusions: a. A minority of 18 percent can win full political rights if it has military and political support fighting on its behalf; b. 200,000 people can become refugees without the world being shocked; c. The nullity of the guarantees of ‘world powers’ has been proven … d. The impotence of the UN in finding an actual solution to crises has been proven once again (if indeed this even needs to be proven).” In another telegram, Vered wrote that “the Cyprus affair has so far demonstrated the impotence of the UN and its inability to solve complex problems such as the Cyprus problem (or, in the past, Vietnam, the Israeli-Arab conflict, Kashmir, etc).”

Apparently, Israel did not learn to be wary of future cooperation with other oppressive military regimes, did not learn that using excessive force can cause a regime’s downfall, and did not learn that upholding violent military rule is perhaps not worth the devastation it inflicted on innumerable citizens. Israel did, however, learn that refugees can be easily deported and that the UN is powerless — though Israel likely knew these things already.

Most read on +972

The story of Israel’s support for the military junta in Greece offers insight into the nature and logic of Israel’s relations with dozens of dictatorships around the world during the 1960s and ’70s. Israel was not interested in the fate of the opposition and left-wing activists who were tortured and murdered by the security forces, nor did it seem to care that its diplomacy, military, and economy were directly aiding in the oppression of millions. This history suggests that the State of Israel was not merely a passive player, following only the will of the great powers; it was and remains a powerful and autonomous promoter of its own interests first and foremost, willing to compromise on values like democracy and human rights in order to gain international support in its own oppression of the Palestinian people.

Hiding the true history of the relations between Greece and Israel is convenient for both countries. The truth is ugly, and it threatens to arouse internal pressure in Greece to end, or at least reconsider, its military and diplomatic relations with Israel today. If more Greeks knew how Israel aided the junta, perhaps they would more readily ally with Palestinians, instead of the state that helped manufacture and uphold the brutal regime responsible for their suffering.

An earlier version of this article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.