A veritable “love blitz.” There is no better way to describe Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s recent outreach to Palestinian citizens in Israel.

There is the bromance with Mansour Abbas, the leader of the Islamic party Ra’am, which nearly gave Netanyahu enough Knesset seats to stay in power, and is one of the core reasons for the breakup of the Joint List. There is the prime minister’s hyped visits to health clinics delivering COVID-19 vaccines in Tira, Umm al-Fahm, Nazareth, and other Palestinian communities.

There was the promise to approve a plan within days to fight crime in Arab society (the days passed and no plan was approved), and the bragging about Government Resolution 922, a massive development plan in Arab communities. And, perhaps more than anything, there is the talk of trying to win Arab votes by communicating with the Arab citizens directly, putting a Muslim politician high up on the Likud candidate list, and perhaps even appoint a Muslim government minister.

“We have at least two mandates [Knesset seats] in Arab society,” Netanyahu was quoted as saying after his visit to Umm al-Fahm. “We love Arabs. When I visited Umm al-Fahm, I was moved that there were so many people asking for selfies everywhere.” A few weeks later, Netanyahu claimed that “the Arab citizens of Israel must be an equal and full part of the Israeli society” during his visit in Nazareth, where he was warmly received by the mayor Ali Salam.

It doesn’t take a professional fact-checker to show how cynical and hypocritical Netanyahu’s new “Arab loving” persona is. Just last March, he erased 15 Knesset seats from his political arithmetic by “demonstrating” on a white board how he, not Benny Gantz, had won the election because some of the Knesset members who had recommended Gantz were — you guessed it — Arabs.

Early last year, Netanyahu embraced Trump’s so-called Middle East “peace plan,” which would have seen Umm al-Fahm — the site of his photo-op with Israel’s “millionth COVID-19 vaccine recipient” — transferred to a Palestinian state, and the man with whom he was photographed stripped of his Israeli citizenship.

In 2018, the prime minister threw his support behind the Jewish Nation-State Law, along with a flood of other discriminatory laws in the decade prior. Over the last three elections, he has aggressively incited against Arab members of Knesset; and back in 2015, he warned his right-wing base that Palestinian voters were heading to the polls “in droves.”

In 2010, Netanyahu embraced far-right politician Avigdor Lieberman’s slogan of “No loyalty, no citizenship,” and attempted to pass a law — aimed at the Palestinian public — that would require a declaration of loyalty to Israel as a “Jewish and democratic” state as a condition for citizenship. Now, he is promising Palestinian citizens equal rights without any loyalty declaration — except maybe to Netanyahu himself — to extend the personal clientalism that is so emblematic of his tenure.

Inciting against Arabs is passé

Despite his centrality in Israeli politics today, focusing on Netanyahu alone misses the larger picture: many right-wing politicians have been falling over each other to sweet talk Arab citizens in recent weeks.

Gideon Sa’ar, a former Likudnik whose right-wing leanings are beyond dispute, has criticized Netanyahu for not doing enough for the Arab community in an interview on the Arabic Nas Radio. Sa’ar, who now leads his own party New Hope, presented his own plan for tackling crime in Arab society and emphasized his commitment to “equal rights for all citizens” — within a “Jewish state,” of course.

Naftali Bennett, chairman of Israel’s far-right party Yamina, began his campaign by declaring that he is “as committed to the citizens of Kufr Qassem as I am to all citizens of the country.” Just a few weeks ago, his party launched a new “Arab-sector field office” in the hopes of getting two Knesset seats from Arab voters in the upcoming elections.

Even Avigdor Lieberman, head of the far-right Yisrael Beitenu, has toned down his incitement against Arabs, and his number two, Eli Avidar, has told Haaretz that he is “vigorously opposed” to the Jewish Nation-State Law, that the “Arab community is amazing,” and that we “need to build a bridge to them.”

In the Israeli center-left, the rhetoric is more straightforward. In early January, Yesh Atid leader Yair Lapid — who normally never forgets to mention that he would only form a coalition with Zionist parties, and has famously said he would not sit with the “Zoabis” (a disparaging remark toward former Balad MK Haneen Zoabi) — wrote on his Facebook page: “We’ve said in the past that we didn’t need the help of the Joint List to form a government. Today we say there’s no reason not to work with those representing 20 percent of the country’s population. We’ve changed, and so have they.”

The “reformed” Labor Party, under the leadership of the newly-elected Merav Michaeli, sees partnering with the Joint List as an obvious point. This is already a far cry from former Labor leaders Isaac Herzog (“we need to shake off the feeling that Labor Party members are “Arab-lovers”) and Avi Gabbay (“We won’t sit in the same government with the Joint List”).

Meretz, meanwhile, has two Arab candidates in the top five spots on its Knesset list, and two of the first four candidates in the new “Democratit” party’s list, which purportedly represents the anti-Netanyahu protesters, are Arabs.

Occupation no longer part of the conversation

What makes all of this particularly perplexing is the fact that this “love blitz” toward Palestinian citizens lacks any talk of peace with the Palestinians or a need to end the occupation of the Palestinian territories: Sa’ar has barely mentioned the conflict, and Bennett has said that he is setting his annexation plans aside. Still, all these right-wing politicians fundamentally reject the establishment of a sovereign, independent Palestinian state and an end to the occupation according to international agreements.

If current polls bear out, the next Knesset will be one of the most right-wing in history. The 80 MKs expected to serve in right-wing parties (including Sa’ar, Bennett, and Lieberman) will likely sign off on any measure designed to further entrench Israeli annexation and apartheid. Should formal annexation become a possibility again — which does not seem likely under a Biden administration — they will all vote in favor.

In other words, the Israeli right, and Jewish politics in general, is embracing Arabs while trying to erase Palestinians. Jewish Israel is tearing down the walls that have separated it from the Arab world — as evidenced by the thousands of Israelis scrambling to vacation in the United Arab Emirates — while fortifying the walls that keep Palestinians away. Arabs are good, Palestinians are bad.

“You’ve seen Jews and Arabs embracing in Dubai and Bahrain. Why can’t we have that here?” Netanyahu wondered aloud after visiting Umm al-Fahm. Speaking to the Likud secretariat, Netanyahu also said, “Just like I broke the Palestinians’ veto over [Israel’s] relations with Arab countries, I’ll break the veto Arab parties have over Israel’s Arab citizens.”

It’s hard to make sense of this gap between the embrace of the Arab and the rejection of the Palestinian without understanding the settler colonialism that lies at the heart of Zionism. The intellectual founders of Zionism had no issue with “Arabs” in principle; Theodor Herzl envisioned Arabs in key positions in his ideal state, and even Revisionist Zionist leader Ze’ev Jabotinsky promised that every government in the Jewish state would have an Arab deputy prime minister. In that sense, both Netanyahu and Sa’ar can rely on Jabotinsky’s legacy when they promise equal rights for the Arab community.

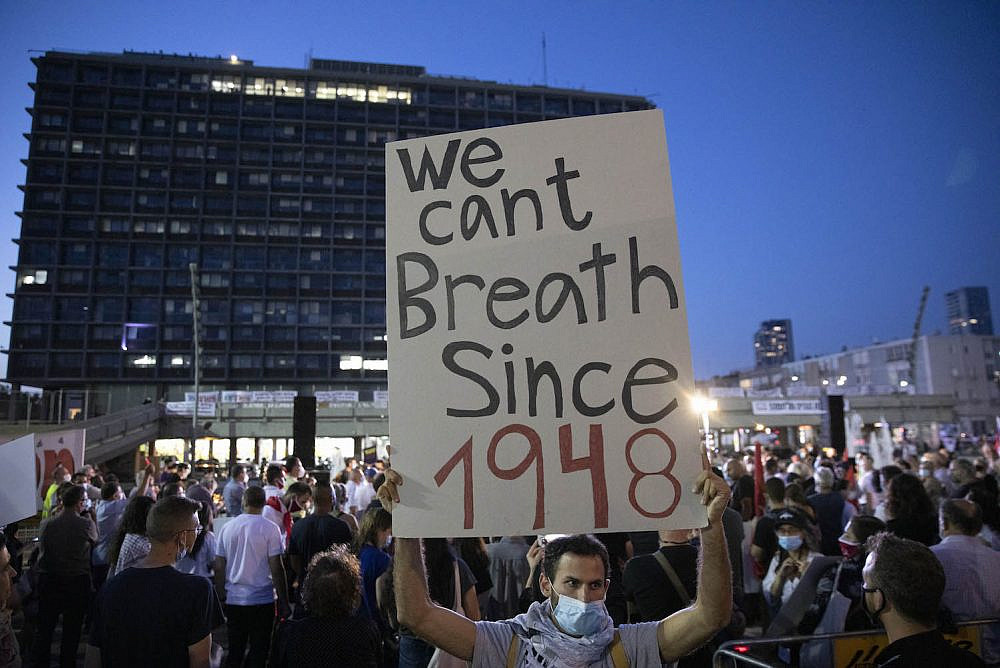

Mainstream Zionism, however had an incredibly difficult time recognizing the indigenous people of the land as a national group, with national rights equal to any rights Jews had to Palestine/The Land of Israel. After 1948 and the Nakba, this was compounded by Israel’s refusal to admit that the Jewish national entity was violently built on the ruins of Palestinian society, whose members were forcibly expelled and dispossessed.

Netanyahu wants the Palestinians to give in

The Jewish-Palestinian story is not that different from the history of settler colonialism elsewhere. Following on the work of scholars like Lorenzo Veracini and Patrick Wolfe, four phases can be identified in the development of settler colonialism (see also this lecture by Dr. Yosef Rapoport marking 100 years since the Balfour Declaration).

First, the settlers attempt to imitate the indigenous population. Next, they try to take the place of the indigenous people. This is followed by a war for domination between the settlers and the indigenous people. Finally, the victors extend a hand to the losers, bringing them into the fold after the latter admit defeat. In North America and Australia, this ended with victory for the settlers. In Algeria and South Africa, the indigenous people won.

The third phase of the Jewish-Palestinian conflict took place in 1948, leading to a resounding victory for the Jews. But for decades the Israelis had trouble transitioning into the fourth phase. Netanyahu is now trying to move Israel into that phase. Staying true to Jabotinsky’s “Iron Wall” thesis, Netanyahu believes Israel is now strong enough to bring the “natives” into the fold — even as he strips them of their national identity.

This is emerging as one of the goals behind the agreements signed with Arab states in recent months: using Israel’s power with the Arab world to send a clear message to the indigenous people that they have no choice but to surrender, give up their national narrative, and accept Jewish supremacy — albeit in a “softer,” more “egalitarian” language.

What Netanyahu and many others in Israeli politics fail to understand is that this is a non-starter. The people of Umm al-Fahm may be Arabs, but they are also Palestinian. In that sense, the separation between Israel from the West Bank and Gaza Strip is an artificial one. In terms of identity, there is no real difference between a so-called “Arab Israeli” and a Palestinian, whether he or she is a citizen of Israel, a resident of the West Bank or Gaza, or a refugee outside of Palestine.

The absence of a strong, official Israeli identity has made it difficult to “swallow” Palestinian citizens of the state, which in turn, has helped ensure they remain part of the Palestinian nation — even if they are considered a “special case.” Even Mansour Abbas of the Ra’am party has steered clear of discussing occupation and apartheid, because he cannot and does not want to renounce this identity.

Partnership and supremacy don’t go together

The wider Israeli-Arab conflict might have begun moving toward its conclusion with the signing of the peace accords with Egypt and Jordan, and later with the UAE, Bahrain, Sudan, and Morocco. But the Jewish-Palestinian conflict remains — from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea.

Then again, history suggests that even if this “love blitz” is designed to erase the Palestinian story, it may have unintended outcomes. The very fact the Palestinian Arab minority in Israel has become a player in the political field; the legitimacy of this public’s elected officials; the recognition of its culture; and the growth of its economic and social power, could, down the line, chip away at the foundations of Jewish supremacy that have propped up the State of Israel since its inception.

These developments may also force Israel’s Jewish politicians to realize that, at the end of the day, it is impossible to “swallow” the Arabs without recognizing that they are Palestinian. Perhaps they will recognize that it is impossible to create a normal society so long as occupation and apartheid persist, and so long as a Jewish state continues to mean Jewish supremacy over the indigenous Palestinians, with or without Israeli citizenship. Exclusive Jewish rule over non-Jews cannot continue forever.

On another front, the “love blitz” waged by Netanyahu and the right wing has put both Palestinian and Jewish left-wing politics in Israel in an awkward position. If Netanyahu says Jews and Arabs must “reach out to each other” and work together in the noble pursuit of equality and mutual respect, then what does the left actually mean when it refers to “Jewish-Arab partnership?” How is it different from the right’s version?

The solution may lie precisely in recognizing this difference. The right-wing version of Jewish-Arab partnership mainly involves acknowledging Arab citizens’ individual rights, language, and culture, and perhaps equality when it comes to state budgets.

Real Jewish-Palestinian partnership, though, requires rectifying the injustices of the past and redistributing power in the present. It requires two co-nations living in the same space between the river and the sea. Only when we adopt this premise will we be able to speak of true equality, rather than stretching the rights of Palestinian citizens of Israel as far as Jewish supremacy will allow. Writing Palestinians a check simply won’t cut it.

This article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.