Back in the 1970s, the deep socioeconomic divide between Ashkenazi and Mizrahi Jews in Israel led to a massive protest movement and the rise of the Israeli Black Panthers. A newly approved official civics textbook in Israel portrays the movement as violent and criminal. We called up three Black Panthers to remind us all of the true nature of their struggle.

The following is a chapter in the Education Ministry’s newly-approved civics textbook, To be Citizens in Israel:

Criminality motivated by ideology — political violence

“Political violence is the use of force by an individual of a group in order to attain political goals such as influence, protection of the government, protest against the government, or struggle against another group which has social or political power.

Political violence can begin with verbal violence, through demonstrations and protests without a permit, physical confrontation with security forces, property damage, beatings, causing bodily injury and wounds, and can go as far as murder. In some cases, political violence has as its goal the intimidation of opponents or enemies, at which point it constitutes terrorist activity.”

Expressions of political violence in Israeli society

Violence in the context of the national divide, as manifested during “Land Day” and the events of October 2000 by Arabs against Jews (in contrast, the Or Commission found that the police, too, reacted with excessive force in some cases, and 13 Arab citizens were killed), “price tag” activities and the murder of the boy Mohammad Abu Khdeir in 2014 which were carried out by Jews agains Arabs.

Ideological-political violence, such as the murder of Emil Grunzweig in 1983 during a Peace Now demonstration, and the assassination of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin.

Violence based on a feeling of ethnic discrimination, for example the events of Wadi Salib in the 1950s, and the demonstrations of the Black Panthers in the 70s.

Violence in the context of the religious divide, such as throwing stones at cars driven on the Sabbath, and the murder of the young girl Shira Banki during the Pride Parade in 2015.”

Ethnic discrimination is based on “a feeling?” Perhaps it is just a figment of that famous Oriental imagination? And criminality? Is this how Israeli children will learn about one of the most important events in the history of the Mizrahi and social struggles in Israel? Not to mention the fact that the textbook frames Shira Banki’s murder at the Jerusalem Pride parade in the context of religion, or that so-called price tag violence is framed as “ideological-political” — but that is another matter.

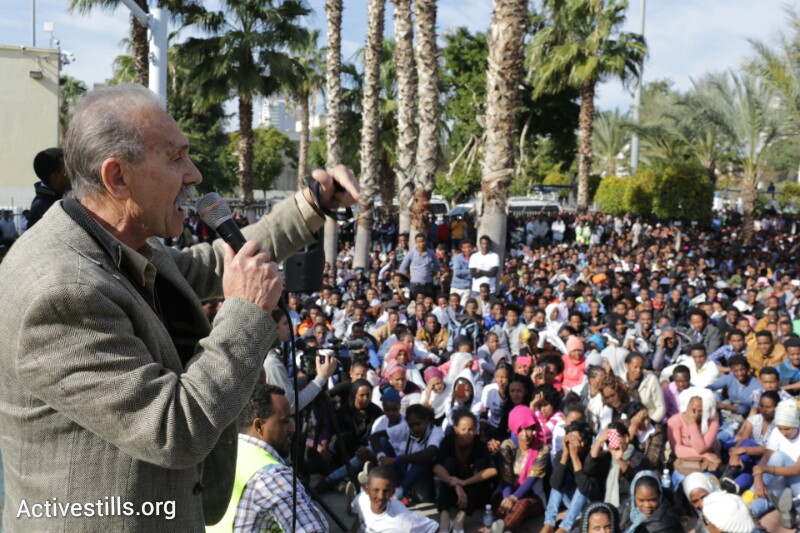

We decided to call up three members of the Israeli Black Panthers, who were not surprised by the news and hastened to correct the definitions. Here is what they had to say:

Reuven Abergel:

In order for young people to form a balanced judgement, government violence — which is somehow missing from the textbook’s description — has to be added. Government violence is the violence of the pen pushers. People in suits and ties sitting in air-conditioned rooms, who with a stroke of a pen liquidate a hundred thousand people with the pretense of having ringworm; with a stroke of a pen they declare war on “the enemy” and send people to their death. This is a silent form of violence that is not widely perceived as criminal, but is in fact far more violent.

The definition laid out in the textbook assails a group of people who sought to defend their rights; it essentially runs counter to the very basis of democracy, considering that democracy calls for accountability where there is none. This does not surprise me. Until this very day, the Israeli establishment and the political system have been abusing groups of innocent people simply because they belong to a certain group. Even before the arrival of these groups here, in 1949, there was a campaign of mudslinging, demonization and delegitimization against a group of people who had not yet reached Israel, through vilifying publications by Aryeh Gelblum (“The primitiveness of these people is unsurpassable. As a rule, they are only slightly more advanced than the Arabs, Negroes and Berbers in their countries”) and his ilk. This racist slander has continued until today.

Those who adopt a racist attitude against Mizrahi Jews are occasionally awarded prizes by the government. We citizens have no recourse but to defend ourselves against the political violence by the Ashkenazi elite toward Mizrahim.

As a Black Panther, I understood back then that I live in a country run by Eastern European Jews, who have partners in the U.S. who support them and back them up. Organizations like AIPAC collect the fee — the price of our oppression — and split it among themselves.

The Black Panthers, the second generation of persecuted Mizrahi Jews, found themselves destitute and devoid of rights. We were innocents persecuted by the state, and the only way to challenge the establishment was to take to the streets and make our voices heard. The political system encourages and justifies government violence against citizens. When a citizen comes out with his story he is turned into an enemy, and is portrayed as such in the educational curriculum.

Charlie Biton:

Since the establishment of the state, every time Mizrahi Jews demonstrate they are portrayed as monsters. We are criminals, we go wild, we riot, and the Ashkenazi Jews — when they demonstrate the term “protest” is used. The Wadi Salib uprising were called “riots. As for the Black Panthers, instead of engaging with our demands or understand why we were protesting, we were deemed “rioters.”

In Israel there are two ways of dealing with two types of population: Ashkenazi and Mizrahi. We are not accepted by the establishment and we struggle against it. On the other hand there are nice Ashkenazim; even when they are angry with the establishment, they do it with excessive gentleness. Even when they get upset they are treated with more tolerance.

Kohavi Shemesh:

This textbook definition is completely idiotic. You cannot define the struggle of the Black Panthers, since no definition will fit. But those who wrote the book did a foolish thing, because they are taking us backwards. Do they want us to restart the struggle?

The era of the Panthers is finished, but the story of the day is not criminality or violence, but rather “an unfinished social struggle.” This is an important point worth making: this struggle has not exhausted itself. The flagrant inequality that caused us to take to the streets still exists. Calling us criminals is simply blaming those who wanted to remedy and protest injustice. Where is the establishment’s role in the definitions? Where is the inequality? The injustice? Isn’t this criminality?

In our times, too, all kinds of social struggles are taking place, which are in many respects an outgrowth of our struggle. This definition is simply stupid and has no connection to reality. The struggle of the Panthers was a struggle for bread, for rights, for equality, and against exclusion and discrimination. To characterize it as criminal is negligent at best — in the worst case it is a direct continuation of that very racism.

This article was first published in Hebrew on Haokets. Read it here.