For most of Israel’s minority groups, the Jewish Nation-State Law was far from surprising. But for many Druze citizens, who for decades have served in the military, it was the straw that broke the camel’s back.

Eman Safady, like many Druze citizens of Israel, felt personally betrayed by the Jewish Nation-State Law. A journalist from the village of Abu Snan in the Galilee and an officer at the Union of Journalists in Israel, she was one of the tens of thousands of protesters who took to Tel Aviv’s Rabin Square last weekend to oppose the law.

The Jewish Nation-State Law did not shock most of Israel’s minority groups. The law is merely a symbolic acknowledgment of a discriminatory reality they’ve long grown accustomed to, in which Israel and its institutions favor Jewish citizens over non-Jews. The law explicitly declared that Israel belongs not to its citizens but to the Jewish people, and stripped Arabic of its status as an official language.

For the Druze community, which has traditionally been categorized differently than other Arabic-speaking, non-Jewish minorities in Israel — the law elicited strong feelings of abandonment.

“They’re trying to anchor our second-class status in law,” said Safady. “Before, I would feel discriminated against, particularly as a woman. But now our inequality is being flaunted in our faces.”

Lately, Safady continued, it seems the Israeli government has been trampling on everybody’s rights, be it the LGBTQ community fighting for equality or secular and non-Orthodox Jewish Israelis advocating for stronger separation of religion and state. This sense of urgency has contributed to the outrage, she said. But there is also another shift taking place — one that began several decades ago.

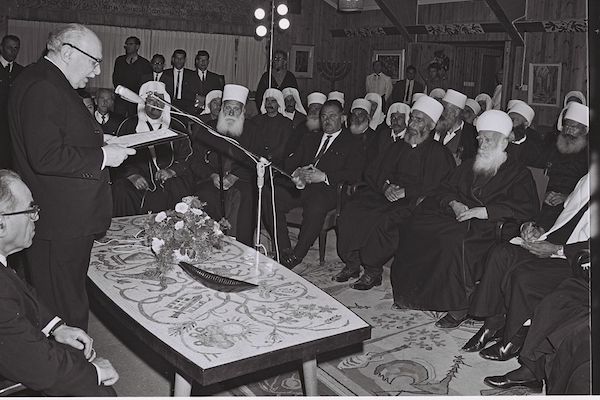

Israel recognized the Druze community as a distinct ethnic and religious minority, separate from Arab groups, in 1957. According to the Central Bureau of Statistics, as of 2017, there were approximately 141,000 Druze in Israel, or 1.6 percent of Israelis. The population grew when Israel annexed the Golan Heights in 1981, although the vast majority of Druze from the Golan never took Israeli citizenship.

In the mainstream Israeli narrative, the Druze are loyal to the state — an anomaly in Israeli perceptions of its minority populations — most visibly because they serve in the military. In the Israeli lexicon, the relationship, with an eye on military service, is commonly referred to as a “blood covenant.” This tradition began in 1956, when a few Druze leaders requested that mandatory conscription — which excludes other Palestinian citizens of Israel — apply also to the men in their community. Since then, enlistment rates have been high.

But the Druze’s unique position in Israeli society has not improved their social or economic standing. “Druze have weak and relatively poor municipalities, lower educational achievements and access gaps to higher education, high rates of unemployment and under-employment (among women especially, and due in part to their residence in small villages in Israel’s northern periphery), and a lack of land for urban development and growth,” explained a 2018 report by the Inter Agency Task Force, a coalition of North American Jewish organizations researching Israel’s Arab citizens.

Over the past couple of decades, discrimination has become more personal for members of the Druze community, and not even the “blood covenant” has granted them immunity.

“The protest on Saturday was about more than the Jewish Nation-State Law,” said Amir Khnifess, head of the newly-formed Forum Against the Nation-State Law. “We were expressing our anger against [the state’s] discriminatory policies toward the Druze community in housing, labor, agriculture, and education.”

Israeli authorities are reverting to strategies they used in the 1950s, when Israel thought it could expel Arabs by chipping away at their living conditions, according to Salim Brake, an academic who focuses on the Druze community. When young people feel they have no prospects, they leave, which in turn weakens minority groups, he explained.

It was also in the 1950s when Israeli authorities secured a clan system vis-à-vis the Druze by appointing the Tarif family to decide on Druze affairs. “The state would financially support the Tarifs, who, in return, would promote the government’s policies,” explained Brake. “People started realizing that the decisions of the Tarif leadership go against the community’s interests.”

The lack of trust extends to Druze members of parliament, added Brake, who he alleged do not seek to represent or serve the community but rather “act as employees of Zionist, fascist parties,” referring to Ayoub Kara (Likud) and Hamad Ammar (Yisrael Beiteinu), two Druze MKs who promoted and voted in favor of the Jewish Nation-State Law.

The law is more dangerous than most people understand, continued Brake. “It persecutes our children, our children’s basic rights, and paves the way for other racist laws. It deprives Arab citizens of any political agency.”

The Arab Higher Monitoring Committee, an umbrella organization that represents Arab citizens of Israel, has launched a separate campaign from the Druze.

“They divided us [Arabs] from the start and we agreed to it. We didn’t mind until it started affecting us as well — until we felt the pain ourselves,” said Nadia Hamdan, head of the northern branch of Na’amat, the largest women’s movement in Israel, which is affiliated with the Histadrut, Israel’s historically Zionist labor federation.

Growing up in Israel, most Druze are taught that the military is an integral part of their lives and their position in society, Hamdan continued. “We were raised with military uniforms on our washing lines.”

The issue of military service has been brought up by some Druze, as well as Jewish Israelis who oppose the law. Unlike the rest of the Arabs in Israel, the argument goes, Druze are entitled to full equality through a political paradigm that supposes “no rights without responsibilities.”

The same idea is the basis of a deal Prime Minister Netanyahu is attempting as part of his attempts to smooth things over with the Druze community. So far, Druze leaders have rejected that approach.

“Those who say that we deserve more rights because we serve in the military are wrong. The state is discriminating against all of us,” said Hamdan. “I want to exercise my right to live in dignity — just like people in the kibbutzim and places like Kfar Vradim — regardless of whether I serve in the military or not.”

That sentiment, that equality must be guaranteed irrespective of military service, was also on display at the protest Saturday night — at least from the Druze speakers and demonstrators.

And yet, even at the height of their outrage, the Druze protesters waved Israeli flags and organizers sang the national anthem, Hatikva, on stage. Both Brake and Hamdan disagree with that strategy, but Hamdan believes that at this point in time, unity is the greater imperative.

“We have to focus on making this a mass movement,” Hamdan concluded. “We woke up a minute too late, but now we have to get on the next train.”