The Israeli army unit that administers the occupation has not updated its website for over five months. Instead, it religiously updates its Facebook page with impressive stats and jazzy graphics — in English only. What’s going on?

“Last week there were a total of 6,735 crossings between Gaza and Israel,” COGAT, the administrative arm of the Israeli occupation chirped on its official Facebook page last Sunday.It is a standard social media update for the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories, a unit of the Israeli Defense Ministry that oversees the occupation in the West Bank and Gaza. (COGAT controls movement in and out of Gaza and the West Bank, allocates resources to Jewish settlements, and is the final word on distribution of land in Area C of the West Bank.)

Nearly 7,000 crossings sounds like a lot. It’s easy to imagine thousands and thousands of people bustling in and out of the Gaza Strip and COGAT’s presentation of this statistic does not give rise to any questions about its true meaning. Yet this number is not what it seems.

A recent blog post by Gisha, a legal NGO that works to protect Palestinian freedom of movement, challenges COGAT’s numbers on several fronts. Firstly, the crossing figures don’t distinguish between crossings and number of people crossing. If someone leaves Gaza and returns on the same day, for instance, a frequent condition of travel permits for Gazans, they are counted twice.

Secondly, the figures are devoid of any context. As Gisha asks, “Is it a dramatic increase or a slight decrease compared to last month? How about compared to last year or 15 years ago? … Is this a lot or a little for a population of 1.8 million?”

As it turns out, comparing the figures to those 15 years ago takes a lot of the shine off them. In 2000, before Israel levied harsh travel restrictions on Gazans amid the Second Intifada, Gisha notes, “500,000 exits by laborers were recorded at Erez Crossing every month – that’s more than 20,000 people a day (or 40,000 if you want to count their entrances and exits).”

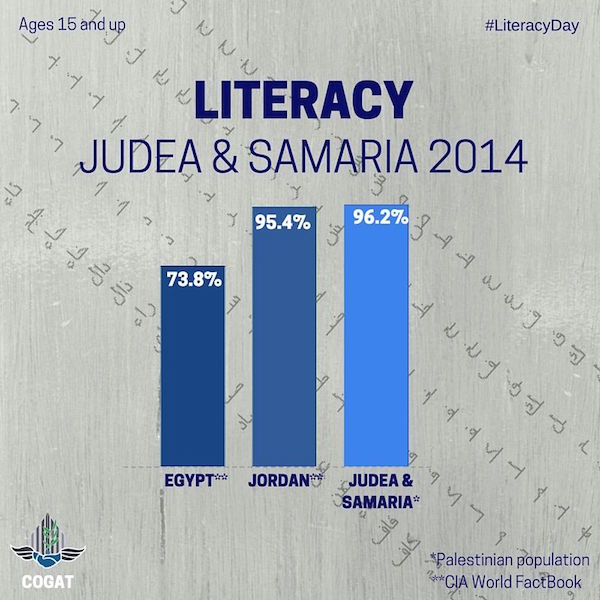

In addition to lots of isolated statistics on the noblesse oblige of Israel’s governance in the occupied territories, COGAT’s Facebook page also offers up statistics on how Palestinians are thriving under occupation (not least in comparison to their uncolonized peers in the Middle East). Moreover, all of this information is provided solely in English, making it fairly clear that the target audience is not Palestinians, or even Israelis.

These social media updates are, then, little more than a PR exercise. They don’t seek to genuinely inform, just to window-dress. This is all very cynical and manipulative of course. Yet COGAT’s dodgy statistics are just the tip of the iceberg: the Facebook page masks a far more fundamental problem.

When COGAT first launched its Facebook page on June 1, 2015, it appeared to be a standalone hasbara initiative. Given its topical content, the page certainly didn’t seem to be a replacement for COGAT’s website, which is supposed to be an essential resource for COGAT to keep Palestinians in the occupied territories apprised of changes in policies or procedures that may affect them. Yet approximately two weeks after the Facebook page was launched, and to considerably less fanfare, COGAT stopped updating its website.

Over five months later, the website remains inactive. Neither the Arabic, Hebrew or English versions of COGAT’s site have seen any updates since around mid-June. According to COGAT, they are working to fix some technical difficulties.

This issue came to light almost by accident when Gisha inquired as to the progress of a freedom of information request it submitted to COGAT back in May 2014.

The request petitioned COGAT to publish the protocols and procedures that govern its activities. As Gisha notes on its website, access to COGAT’s procedures is essential for the 2.6 million Palestinians living in the West Bank and the 1.8 million Palestinians living in Gaza to be able to exercise their rights.

The documents cover dozens of practical administrative issues such as, inter alia, the procedure for issuing entry permits from Gaza and the West Bank into Israel, dealing with medical requests from Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank and arranging for Palestinians to travel between Gaza and the West Bank, etc.

COGAT had originally said that it did not have to make these documents available to the public, despite a 2013 note from the Justice Ministry saying that COGAT is indeed legally obligated to publish them under Israel’s Freedom of Information Act. However, COGAT eventually conceded and committed to make the policies and procedures available to the public in three phases, beginning in February 2015 and ending in June 2015.

While COGAT’s roll-out of policies and procedures did eventually commence, it has been slow to translate them into Arabic, the key language if they are to fulfill their purpose — i.e. keeping the occupied Palestinian population informed as to how it can navigate the military occupation it are subject to. Furthermore, the fact that the website has not been updated since June means that Palestinians have not been kept abreast of changes to protocols or policies, such as those on travel, which are frequently modified. Nor have any reports on COGAT’s activities been released since then, beyond the sprinkles available on their social media pages.

And yet, throughout all the apparent technical problems with its website and as it delays releasing essential information, COGAT has been prolifically updating its Facebook and Twitter feeds with jazzy infographics and saturated facts that are low on context and high on the benevolence of its military rule.

COGAT’s procrastination over keeping Palestinians informed also has legal ramifications. Speaking with +972 Magazine, Gisha spokesperson Shai Grunberg explained that every administrative authority in Israel must publish information that is relevant to the public. “Not publishing this essential information is a breach of the law,” she added.

It is easy to focus solely on the physical violence of the occupation. After all, guns, tear gas and arrests are far sexier than official documents, petitions and bureaucrats. Yet it is this element, the structural violence of blocking Palestinians at every turn with the swish of a pen or the tap of a key, that drives the occupation.

And the Facebook page? That is simply a lesson in how to market the occupation. It is another indication that the Israeli government’s prevailing concern is how its control over Palestinians appears to the world, and not whether it exerts that control in line with even its own laws.