“Meir Kahane: The Public Life and Political Thought of an American Jewish Radical,” by Shaul Magid, Princeton University Press, 2021.

On Feb. 25, 1994, Baruch Goldstein, an American immigrant to Israel, opened fire in the Ibrahimi Mosque/Cave of the Patriarchs in occupied Hebron, murdering 29 Palestinian worshipers and wounding 125 before being killed himself by surrounding survivors. Goldstein, a Brooklyn-born graduate of Yeshiva University, was a devout follower of the American Orthodox rabbi and one-time Knesset member Meir Kahane, who had been assassinated a few years prior. He had also been a member of two high-profile far-right groups Kahane founded: the New York-based Jewish Defense League, and, after Goldstein moved to the occupied West Bank, Kach — an Israeli political party banned by the authorities in 1994 following his terror attack.

The Goldstein massacre thrust Modern Orthodox Jewish leaders and intellectuals in the United States into a painful debate about American Orthodoxy, religious Zionism, and violent extremism. Some claimed there was “something rotten at [the] core” of American Modern Orthodoxy that allowed such violent sentiments to go unchallenged; others criticized it for being “too tolerant of Kahane’s extremism.”

“It makes no difference how ‘tiny’ the number of Kahane followers is, if their doctrines do radiate. And they do!” wrote Rabbi Hillel Goldberg in the pages of Tradition, the journal of the Orthodox Rabbinical Council of America. Instead of dismissing Goldstein as a madman or his actions as the outgrowth of a fringe Israeli subculture, these critics pointed to the presence, or even roots, of this radicalism in their own spaces.

Indeed, according to a new biography by scholar Shaul Magid, Kahane represented the “underbelly” not only of American Orthodoxy, but of American Jewry writ large. In “Meir Kahane: The Public Life and Political Thought of an American Jewish Radical,” Magid — a professor and Distinguished Fellow in Jewish Studies at Dartmouth College — invites all mainstream American Jewish institutions to grapple with their role in creating Kahane and perpetuating his ideas today.

Menachem Butler, an American researcher on Jewish law, has suggested that the rabbi is a kind of Rorschach test for American Jewry: that the various ways Jews remember Kahane and his legacy reveal more about how they view themselves and their community than about Kahane’s life itself. Mainstream Jewish institutions have condemned Kahane’s racist violence and minimized any shared heritage with him, his followers, and his ideas, in deference to a self-perception among American Jews as an exceptionally progressive community with stalwart liberal commitments.

Over the decades, liberal American Jews have managed to mostly limit introspection about Jewish reactionary violence — when they have entertained it at all — to the Israeli military, or to a few extremist West Bank settlers, not least Goldstein. These reflections maintain a thick line of separation between “us” (moderate, reasonable, peaceful Jews), and “them” (extremist, fundamentalist, and violent Jews). But Magid’s induction of Kahane as a quintessential, canonical American-Jewish thinker explodes any attempt to disaffiliate Kahane from mainstream American-Jewish life. In this, Magid reflects a recent spirit of reckoning with the violent and chauvinistic undercurrents of American society, pursued with renewed urgency during the Trump era.

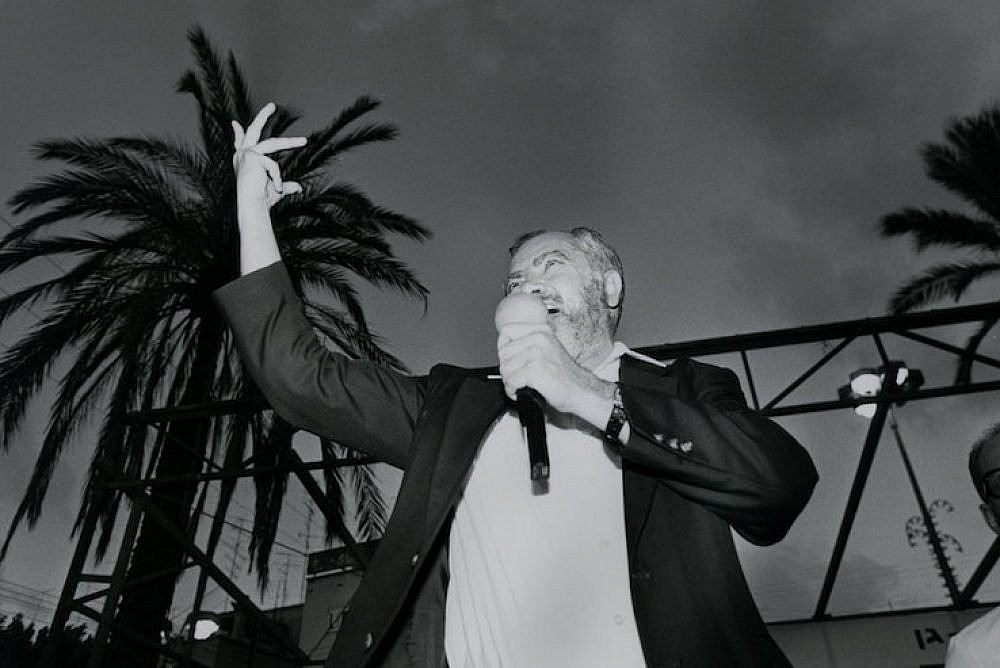

It is against this backdrop that Magid has systematically analyzed Kahane’s voluminous writings, joining other scholars who have disproved the idea that there was ever a Jewish liberal consensus in the United States. The biography pushes those who would dismiss Kahane as a fringe extremist to reckon with the fact that many of his ideas are today uncontroversially embraced by American-Jewish organizations, not to mention the Israeli government. These include Kahane’s denunciations of assimilation and intermarriage; his support for Jewish settlements in the occupied territories; his obsession with “black antisemitism” and antisemitism on the left; and his promotion of nationalism and militarism. And although Magid acknowledges that Kahane was a “middle-brow thinker,” more skilled as an orator and youth leader than as an original theoretician, he takes Kahane’s philosophy seriously precisely because of its widespread acceptance.

Rooted in American radicalism

In assessing the context of Kahane’s rise to prominence, Magid delves into the major themes in Kahane’s writings — liberalism, racism, communism, Zionism, and apocalypticism — and finds that his ideology is rooted in the American radicalism of the 1960s, and in the Jewish culture wars of the same decade. Magid emphasizes the parallels between Kahane and his leftist contemporaries in the 1960s, noting that the relative post-war stability of American Jewry generated both Jewish conservative reaction and radical Jewish leftist protest — with the boundaries between the two at times blurred. Kahane’s calls for militant Jewish pride, liberation, and the overthrow of the Jewish establishment were at times, Magid argues, virtually indistinguishable from those of contemporary Jewish New Left groups such as Jews for Urban Justice, the Jewish Liberation Project, and the Radical Zionist Alliance.

Kahane, like many Jewish thinkers and organizations, consciously borrowed language and tactics from the Black Panthers and the anti-colonial freedom movements of the 1960s, delighting when opponents labeled the JDL the “Jewish Panthers.” Magid writes that in his militarist aesthetics, anti-colonial rhetoric, and revolutionary violence, “Kahane should be placed alongside Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael [Kwame Ture], and the Jewish Defense League should be viewed alongside the Black Panthers and the Young Lords.” In this vein, Magid’s book delves into the resemblance between Kahane, Black nationalist thought, and Jewish New Leftist thought, while downplaying the parallels between the JDL and similar white ethnic revival initiatives such as mafia boss Joseph Colombo’s Italian-American Civil Rights League, with whom Kahane frequently collaborated.

Kahane’s leftist contemporaries also noticed the similarities. Magid quotes famed anti-War Yippie Abbie Hoffman saying of Kahane, “I agree with his methods but not his goals,” while another quoted Jewish New Leftist wrote that the JDL’s “attacks on the Jewish Establishment in America are almost totally valid.” Non-communist leftists maintained an ambiguous attitude towards the JDL, acknowledging that it appealed to “Jews with real problems.” But they recognized that Kahane’s desired ends — racial purity laws, ethnic cleansing, violent suppression of the left, and the aggressive deployment of U.S. and Israeli armed forces — were in direct opposition to those of the Israeli and American left. Magid concedes these different goals, but argues that analyses that prioritize these difference are “too wedded to ‘politics.’”

The equation of Kahane’s anti-liberalism and style with that of the far left echoes the perspectives of Cold War liberals who decried extremism from the right and left. This focus on the equivalency between the left and right, and their mutual distance from a presumed center — a framework known as “horseshoe theory” — has been used to argue, for example, for the presence of overlaps between Soviet and Nazi totalitarianism or between the anti-establishment rhetoric of Senator Bernie Sanders and Trump.

Assessing Kahane alongside the radical left certainly illuminates a shared right-wing and left-wing kinship of rage and disgust with liberalism. But these comparisons may also create the impression that disruptive protest and armed nationalism were the unique contributions of the left to the 1960s, when these tactics were in fact successfully and imaginatively wielded by right-wing anti-communists and conservatives in the United States and beyond. Populist rights-based rhetoric, rejection of liberalism, and anti-elitism are not inherently leftist or revolutionary tactics, but rather neutral forms that can be directed toward various political ends.

Jewish ‘Middle America’

Earlier scholarship and reporting offer an alternative approach to understanding Kahane and the JDL — one which places them within the same late 1960s timeframe, but rather links them with the white backlash to Black freedom that energized anti-integration activism across the country and generated a politics of resentment among so-called “Middle Americans.”

An invented category, “Middle America” was the moniker given to purported hard-working, God-fearing white citizens who felt left behind by the dramatic changes ripping through the United States at the turn of the decade, including the Civil and Voting Rights Acts, a sexual revolution, leftist militancy, declining traditional morals, and urban unrest. Amid resentment at their perceived loss of status, and squeezed by rising taxes and a declining economy, Middle Americans denounced increased spending on welfare as “handouts” to minorities and affirmative action as “reverse discrimination.”

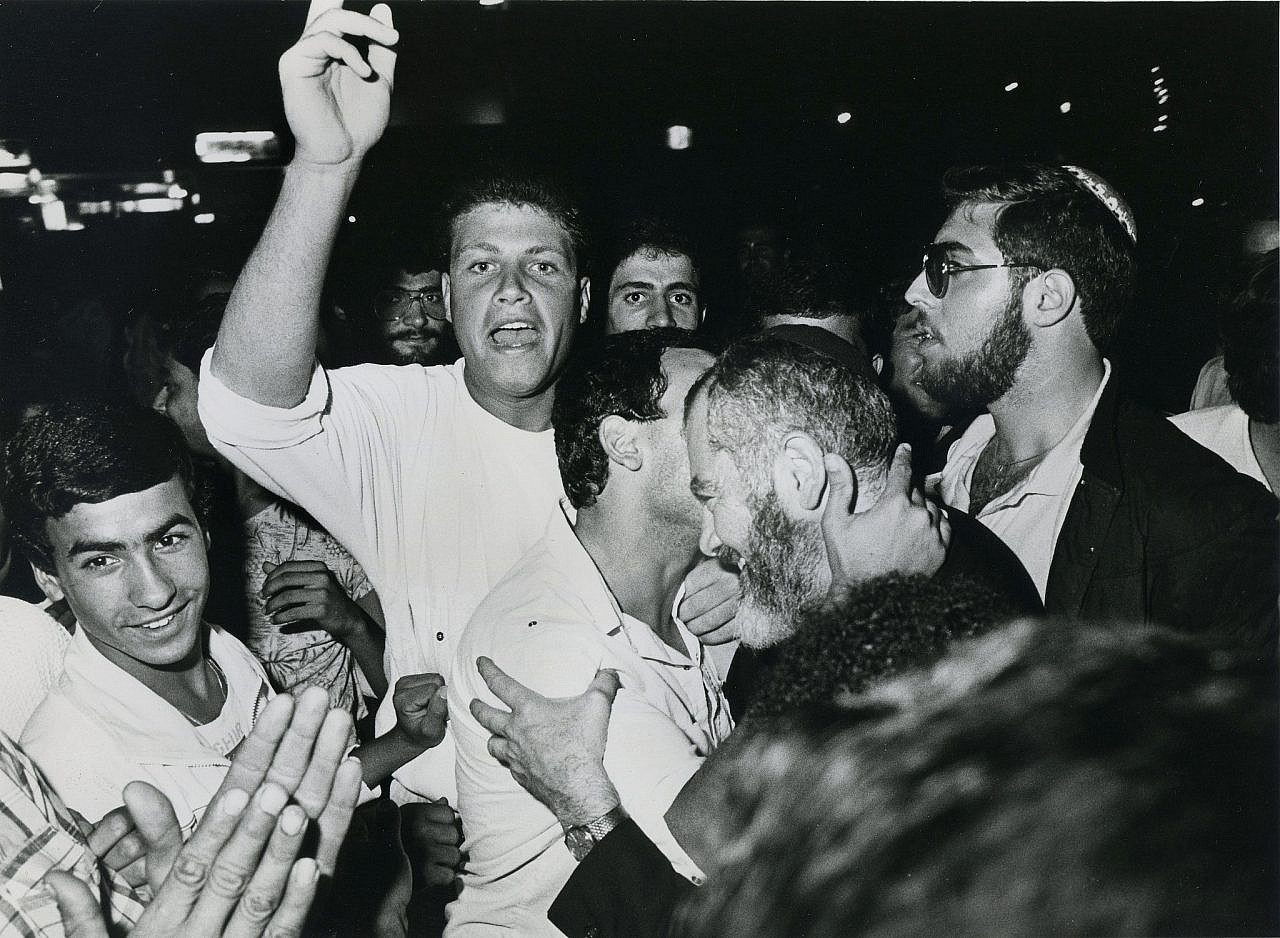

Kahane found great success appealing to the Jewish “Middle Americans” during this period. Among his constituents were elderly and Orthodox Jews, recent genocide survivors, and working-class Jews who did not make enough money to move to the bourgeois “gilded suburbs of Great Neck and Scarsdale” — Kahane’s characterization of relatively well-to-do areas of New York — and so remained in the euphemistically-termed “changing neighborhoods” in Brooklyn and Queens as the Black and Puerto Rican populations increased.

In Kahane’s rendering, the enemies of Middle America — intellectuals, coastal liberal elites, and Black militants — became, respectively, the “liberal American Jewish establishment,” privileged self-hating Jewish leftists, and Black antisemites, all posing an existential threat to world Jewry. These enemies were the pretext for Kahane, together with a few friends, to form the JDL as a civilian patrol in 1968. JDL members quickly armed themselves with baseball bats and chains and set about stalking those same “changing” Brooklyn and Queens neighborhoods.

With his organization behind him, Kahane claimed to be the authentic voice and protector of the Jewish masses, a status he used to rebuff Jewish leaders’ criticisms of the JDL’s tactics. A typical example is a 1970 exchange, via a New York Times report on the JDL, between Kahane and Rabbi Maurice Eisendrath, the president of the Reform movement’s Union of American Hebrew Congregations. After hearing that Eisendrath had referred to the group’s patrols as “goon squads,” Kahane retorted that such attacks showed how out of touch the wealthy Reform-dominated establishment was with the realities of American-Jewish life. “How can a rich Jew or a non Jew criticize an organization of lower- and middle-class Jews who daily live in terror?” Kahane said. “The Establishment Jew is scandalized by us, but our support comes from the grass roots.”

As Magid explains, Kahane’s ambitions extended beyond a limited neighborhood law-and-order agenda. The JDL’s program of intimidation and street violence promised not just white neighborhood control, but also the refashioning of American-Jewish identity. Upward mobility, suburbanization, and decades of liberal equality had, for Kahane, turned American Jews into emasculated, self-hating patsies and WASHs (White Anglo-Saxon Hebrews, drawing on the more mainstream term White Anglo-Saxon Protestants). And like many Zionist thinkers before him, Kahane offered his followers a path to reinvigorated masculinity: a new identity of Jewish virility, potency, and vengeance.

The rabbi further endowed this identity with international implications, drawing on his experiences as a propaganda-man for the Vietnam War, the leader of violent militant actions on behalf of Soviet Jewry, and, in due course, promoter of Palestinian expulsion and subjugation. By flattening the local and the international, Kahane at once elevated Brooklyn to world-historical significance, while imbuing American urban life and street conflict with global political urgency and messianic meaning.

From Cold Warrior to the Knesset

In the 1950s and 1960s, before founding the JDL, Kahane tried his hand as a Cold Warrior-provocateur. Through his childhood friend Joseph Churba, a future Republican foreign policy insider, the rabbi made contacts inside the D.C. intelligence world and went undercover for the FBI in the far-right John Birch Society. He attempted to mobilize support for the Vietnam War by establishing a failed CIA-funded “Fourth of July Movement” targeting college students, and spread the gospel of American anti-communism to the Orthodox community through regular columns in the Jewish Press, a high-circulation New York weekly, in which he declared that “[c]ommunism is to the Jewish soul what Nazism was to the body.”

To this end, Kahane argued that only American victory in Southeast Asia would curb the global expansion of communism and thus ensure Israel’s security and protect Jews from the dangers of Soviet antisemitism. And, as Magid shows, this anti-communism motivated Kahane to turn the JDL into the militant, violent arm of the growing mass movement for Soviet Jewry in 1960s and ‘70s.

Kahane finally moved to Israel in 1971, seeking to dodge his mounting legal troubles in the United States over the JDL’s terrorism. After several failed attempts, he won one Knesset seat with his Kach party in 1984, on the back of a right-wing backlash to the Israel-Egypt Camp David Accords and “land for peace” initiatives, which were being implemented by the Likud prime minister Menachem Begin. Kach was disqualified from running in the 1988 Israeli elections, ostensibly over its racist incitement, before its full ban in 1994.

Though the rabbi had espoused similar racism and violence in the United States, Magid writes that in Israel, Kahane’s worldview became increasingly apocalyptic and fascistic, developing theological justifications for anti-Palestinian violence, Jewish supremacy, and territorial expansion. This potent ideology drew in an unstable coalition of American and Soviet immigrants, as well as Mizrahi Jews, for whom the rabbi cultivated a populist message of belonging and ownership in a country that frequently discriminated against and marginalized them — reminiscent, in some ways, of his appeals to Brooklyn’s “forgotten” Jews.

Despairing over the country’s direction, Kahane developed what Magid terms a “militant and apocalyptic post-Zionism,” under which “nonviolence becomes an act of desecration” and only cruelty, conquest, and Jewish supremacy could bring about redemption. Kahane believed that the Zionist establishment in Israel — just like the American Jewish establishment, although for different reasons — was not fit to safeguard the Jewish future. He saw the idea of a “Jewish and democratic” state, which was insisted upon even by right-wing parties, as not only a clear contradiction in terms but also fatal to the viability of the Jewish state and, therefore, the Jewish people.

Expounding on this critique in 1987’s “Uncomfortable Questions for Comfortable Jews,” Kahane wrote that “[i]t is not democratic to demand that one become a Jew to benefit from the Law of Return. And it is certainly not democratic to define Israel as a Jewish State with the implication that one cannot allow non-Jews to become a majority. And this is the real tragedy and dilemma for the poor secular… Zionists… They would dearly love to present Zionism as a paragon of democracy and equality. They cannot.”

‘Judeo-pessimism’

Despite his eventual entry into the Knesset, Kahane’s Israeli career was never as influential or representative as his shorter American one, Magid writes. The rabbi ultimately failed, he argues, to import the typical communal concerns of a 1960s American Jewish minority into a Jewish-majority state with a strong army and bureaucracy dedicated to protecting Jewish citizens.

Whether or not one agrees with this characterization of Kahane’s impact on Israeli politics, Magid’s assessment of the rabbi as a symbol of post-‘60s American thought will undoubtedly reorient the public conversation on Jewish reaction. Perhaps the most compelling evidence for that claim rests in Kahane’s adoption of some of his avowed enemies’ intellectual frameworks. Magid compares Kahane’s understanding of antisemitism to Afro-pessimism, a theory developed by Frank B. Wilderson III and other postcolonial thinkers, calling it “Judeo-pessimism.”

Afro-pessimism posits anti-Blackness as a fundamental element of human existence and separate from other oppressions. In this view, anti-Blackness inherently sees Blackness as the opposite of Western civilization, standing outside of history and humanity. Magid explains that Kahane viewed antisemitism in a similar vein, as “a sui generis and ontological hatred of the Jews,” distinct from all other forms of racism, which do not constitute eternal, metaphysical hatreds. In the Judeo-pessimist view, “Anti-semitism cannot be eradicated or solved, it is in the gentile’s DNA” and “part of the hardwire of human civilization” — making liberalism, democracy, or any other universal program useless in protecting Jews from harm.

Magid shows how this understanding of antisemitism, captured in the rabbinic adage that “Esau hates Jacob” — that gentiles will forever hate Jews — remained the foundation for Kahane’s approach to everything from urban conflict, to the Vietnam War, to Palestinian rights. It also rendered Kahane’s Zionism a movement of an eternally oppressed, colonized minority. Magid notices this approach today in “everything from the [Anti-Defamation League] to the Jewish anxiety about Black Lives Matter and the anti-Israel sentiment in some progressive circles.” Judeo-pessimism, and the brand of Zionism it inspires, are therefore mainstream.

During the Second Intifada, more than a decade after Kahane’s assassination, the spray-painted words “Kahane was right” and “Kahane lives” appeared throughout Israel, and continue to be seen and heard today. The rabbi’s followers uphold his legacy through vigilante violence and Kach spin-off parties. Calls for Palestinian forced expulsions and “population transfers” are no longer taboo. American-Jewish institutions are desperate to distance themselves — and Israel — from this lineage. But as Magid shows in this important biography, by perpetuating a view of Jews as an eternally beleaguered minority who can have no true non-Jewish allies, many of today’s American-Jewish institutions unwittingly communicate, too, that “Kahane was right.”