It’s time to take a look around and see what’s happening off the square, way off the square. Photography by May Castelnuovo.

Click here for the full series.

ISTANBUL/BURSA, Turkey — On the day we arrived, the metro station at Taksim Square was closed. The following day was a Monday. We took the train into town expecting to alight at least one station north of the square. To our surprise, the train went all the way to Taksim. The station was open and we emerged from it with our first sense of normality.

It wasn’t the normal kind of normality. For one, there was a car burning right outside the station, in broad daylight.

But the street-food stalls returned to the square following their weekend break and an overall sense of routine could be felt. Order had been established: The protest movement was in Taksim. The police were in Beşiktaş, and the rest of the city went about its normal business. Daytime is about dancing, nighttime about crying; stuffed clams are yummy, and so is köfte.

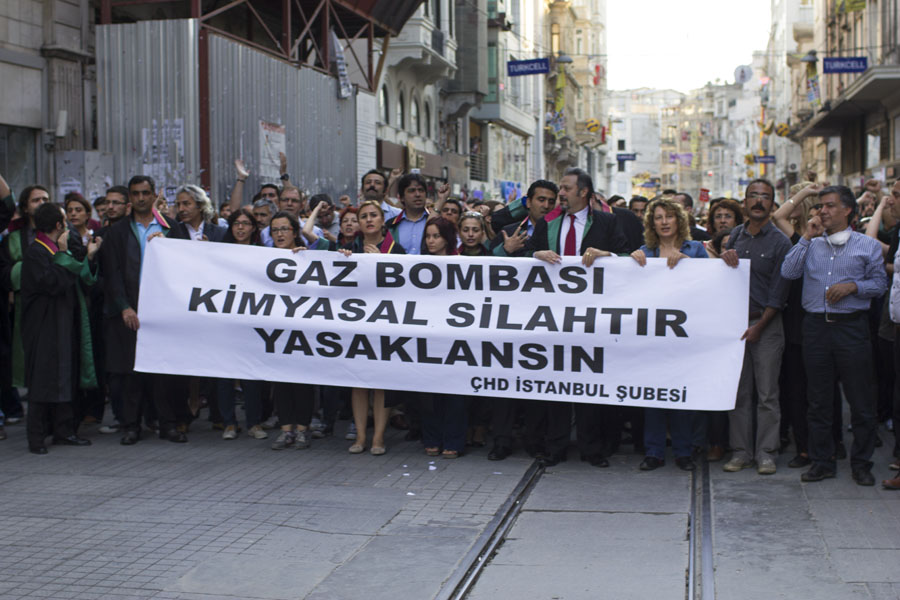

Down on Istiklal, we did witness something unique: a march of Istanbul’s lawyers protesting the use of gas.

This was indeed moving. But by now, on the dawn of our third day, the situation began to seem a bit stagnant. Meanwhile, we are told that other cities are not nearly as relaxed. Last night Ebu Zer showed us a clip filmed in Ankara. In it, a woman is heard begging the police not to gas her residential neighborhood where children are sleeping and older residents suffer from lung ailments. Her plea is not respected. Izmir is said to be the scene of much turmoil, and in Antakya one demonstrator was shot dead.

It’s time to leave Istanbul and we choose the city of Bursa as our destination. It has been the setting of several demonstrations in previous days and is located only three hours away, which would allow us to return swiftly should the police enter Taksim. In the hot afternoon, we board a ferry and head out across the mavi (blue) Marmara Sea.

On board is Turkey’s typical mix of the religious, the secular, the ethnically Turkish and the ethnically otherwise. It’s the very picture of harmony.

Soon, harmony is interrupted by news. All television screens on board erupt into a collage of gas clouds, seen from the police’s point of view, and of necktied parliament members addressing the house. It appears that Deputy Prime Minister Bülent Arinç issued an apology to the demonstrators for the use of excessive force.

Passengers gather around to watch. Arinç is replaced at the podium by Devlet Bahçeli, of the far-right Nationalist Movement Party. A passenger yells, “Fascist!” No one contests. Harmony has returned.

We dock on a beautiful shore and take the bus to central Bursa.

Downtown is a huge square, flanked by a shopping mall. It is the perfect location for a quaint little riot, yet none is taking place here at the moment, unless you consider a bunch of bored teenagers schmoozing by a mall a “sit-in.” Some vendors stand nearby, tossing luminescent blue orbs into the air, catching them as they descend, selling dumb toys in the most boring place on earth.

We ask a group of youngsters about the protests. They direct us to a district called Heykel, and in typical local courtesy, walk us to the dolmus (service taxis) headed there. Heykel turns out to be Bursa’s “uptown,” a leafy business district studded with pretty mosques. Not a whiff of tear gas is felt here. No one is marching nor is anyone dancing. We ask about protests and are told that they take place at a place called Kent Maydani. In typical local courtesy, two locals walk us halfway there.

As we approach Kent Maydani, something does appear to be happening: colorful sparks fly into the air ahead of us. Once we turn the final corner, they reveal themselves to be the silly boomerang toys. We have returned to point zero. Kent Maydani is the shopping mall from before.

We turn to two women in their twenties. They are our last hope. One confirms that a demonstration took place here yesterday. About 400 people took to the streets. Today there is nothing. “It’s over,” she says.

Over, like our own cherished tent protests, like so many other struggles that mattered but were intelligently extinguished by the powers that be. Could one apology have had such an effect? Is it the same sense of stagnation that caused even us to change plans? We leave Bursa discouraged and head back to Istanbul, this time by bus along the Marmara coast. It’s late and the boats no longer run.

Thank God for small surprises. The bus, too, goes on a boat: a basic car ferry allows it to forego skirting the slender bay of Izmit.

We step out and enjoy the sea breeze in the warm June night, the lights on the opposing coasts and a can of Cappy juice. The small surprise is followed by a big one.

She’s an English speaker, a tour guide by trade. Her name is Sonyul and she opposes the protests.

“The Justice and Development Party won most of the votes in the elections,” she says. “It finally managed to bend the army’s arm, that has been interfering in this country’s politics for so long. The Left may think it can offset the democratic order, but that’s not likely to happen. And meanwhile, teenagers are on the street at night, in dangerous situations. This isn’t right.”

Though bareheaded, Sonyul identifies as religious. “We are a Muslim nation,” she says, “not like Israel or countries in Europe. I grew up learning nothing about the Quran, about the Arabic language, but that is contrived. In truth, a five-minute walk from Taksim, most women wear hijabs. This is who we are and this is how we vote.”

Sonyul expresses hope that police will treat the protestors more gently, but her speech remains a clear break from the routine, so much so, that at first she hesitates before letting May take her photo. Her friends are liberal, and may fail to understand. Finally, she performs her own little act of protest and smiles at the lens.