Hendrik Verwoerd, the former South African prime minister regarded as “the architect of apartheid,” should also be known as one of the original architects of the Israel apartheid analogy. In November 1961, he declared in the Rand Daily Mail: “Israel, like South Africa, is an apartheid state,” after taking over Palestine from the Arabs who “had lived there for a thousand years.” Verwoerd meant that as praise, of course; but for others, it was further reason to condemn Israel in African and global forums for its 1967 occupation and other violations of Palestinian rights.

Since then, the Israel apartheid analogy has largely focused on regime policies — legal discrimination, political oppression, and land dispossession — as shown in recent reports produced by local and global human rights groups, echoing the work of Palestinian and South African thinkers and organizations before. Scholarly engagements with the analogy, and political campaigns around it, similarly display almost exclusive concern with the comparison of South African and Israeli apartheid-style policies.

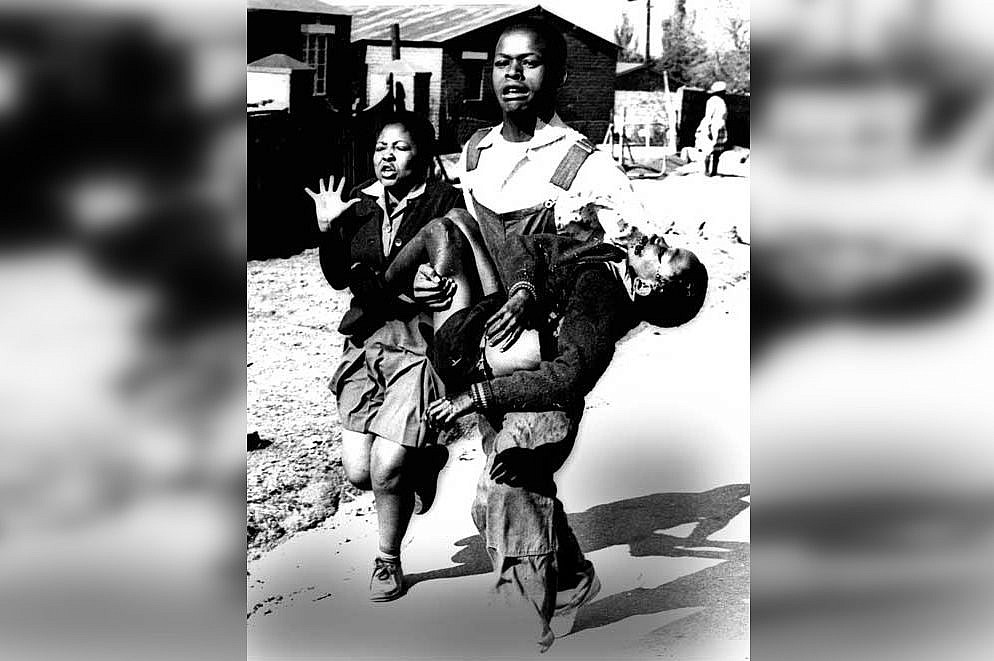

On the ground, though, another dimension of this analogy has long been visible. Since 1948 — the year Israel declared its independence and South Africa officially instituted apartheid — Palestinian uprisings against draconian rule and land confiscations paralleled similar protest actions by Black South Africans. The Land Day protest of March 1976, for example, coincided with the Soweto Uprising in June of the same year; a decade later, the South African township rebellion of the 1980s coincided with the First Intifada that began in December 1987.

In both places it seemed that a spontaneous uprising of young people, supported by community organizations and trade unions, would bring the system of racial domination to its knees. While that did indeed transpire in South Africa, in Palestine success was more limited. A relaxation of direct military rule during the Oslo process was reversed during and after the Second Intifada, with Israel intensifying its policies of dispossession, settlement, and hafrada (literally, segregation).

While the past two decades in Palestine have seen a further entrenchment of Israeli domination, in South Africa there has been a transition to democracy and equality of legal and political rights (albeit with severe economic inequality and ongoing racial disparities). It is no wonder that the success of the anti-apartheid struggle has become prominent as a historical analogy, moral lesson, and strategy for change. But how much does the comparison of the resistance movements truly fit, and what lessons can be drawn from their differences?

Forging an inclusive national identity

My new book, “Anti-Colonial Resistance in South Africa and Israel/Palestine: Identity, Nationalism, and Race” (Routledge, 2022), gives special attention to conceptualizations and strategies of resistance over the course of the last century in the two countries.

The perspective in the book differs from that of other comparative studies of South Africa and Israel/Palestine in three key respects. First, it focuses on the nature of resistance rather than on the system of domination. Second, it looks at nationalist and radical left-wing movements as dynamic forces that responded to social and historical challenges, instead of offering a static set of legal and political principles. And third, it regards South Africa’s political trajectory as a subject in its own right, rather than as a benchmark used to examine the Palestinian struggle.

Much of the existing literature takes the primacy of the African National Congress (ANC) alliance in the anti-apartheid struggle for granted, without studying the historical process of its rise to such a position. In contrast, I examine it as an outcome of competition with other political forces, in particular Africanism and Black Consciousness, that were just as powerful at certain periods.

The unfolding of resistance to domination requires understanding the point of view of activists and intellectuals who were affiliated with anti-colonial movements, and who operated mostly outside the boundaries of the academy. Of most interest are the ways in which they theorized the conditions of their struggles, identified potential allies and actual enemies, defined strategies and solutions, and confronted oppression creatively by formulating principled positions and practical programs of action.

In retrospect, a great historical arc may emerge into view. In South Africa, resistance started from a meager basis. Black South Africans were politically fragmented and socially incorporated, in a subordinated position, into a state that was built through collaboration between various white settler groups. As Black activists gained confidence due to local mobilization, inspired by regional anti-colonial struggles and other global developments, the movement shifted its goals: from seeking inclusion into white-dominated structures to demanding an overhaul of the entire political edifice.

The strategy rested on a solid material foundation: the centrality of Black workers as suppliers of cheap labor that was indispensable to the profitability of capital and the prosperity of white people. It enabled them to use their economic position as leverage for political change within the system. Because of this, the locus of the most crucial political and social campaigns was clearly inside the country; the advocacy and military actions of the leadership in exile and solidarity movements overseas also played important roles, but they hinged on the progress of the internal popular struggle.

In the process, an inclusive national identity was created: South Africa was potentially open to all its people regardless of their racial and ethnic background, and despite varying political emphases on non-racialism, Africanism, and Black Consciousness. The discourse of the struggle — and the ANC’s in particular — combined appeals to specific constituencies defined by their identity with messages that raised universal notions of class, freedom, democracy, and justice. This approach facilitated a move toward a negotiated solution and the political transition of the 1990s that ended apartheid.

Divergent nationalisms in Palestine-Israel

The Palestinian national movement, meanwhile, moved in a rather different direction. Threatened with the loss of their homeland due to the aspirations of the Zionist movement, Palestinians started with a demand for political power as the demographic majority and historical owner of the country. Although they were willing to accommodate Jews as a minority, that was to be done from a position of strength — as a concession — without diluting the Arab claim to the land.

That Palestinians owned most of the land until 1948, and only a few of them were employed by Jews, who in turn never became dependent on their labor, made their historical claim to independence stronger. Crucially, however, it also deprived them of the kind of leverage available to their Black South African counterparts.

That stance was shattered with the 1948 Nakba. Nonetheless, once the movement began to recover from the military defeat and the dispersion of its people, it continued to claim sole ownership of the country. At the same time, it started to shift its position regarding Jewish settlers, who were no longer a minority in the territory: they were still regarded as outsiders whose claims were based on the use of illegitimate force, but they had to be accommodated in any future arrangement — as a concession to reality, not a right.

The slogan of a Secular Democratic Palestine in which all would live equally, adopted in slight variations by Fatah, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), and the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP) since 1970, was a major conceptual breakthrough. But it was formulated within an Arab or a Palestinian-Arab nationalist framework that Israeli Jews never regarded as genuinely inclusive. Whereas anti-colonial nationalism in South Africa encompassed all residents, at least in theory, ethnic nationalism in Israel/Palestine has played a divisive role.

An overarching national identity that would include all groups, even if only in theory, has still not emerged. In the absence of such an identity, compromise solutions from the late-1970s onwards have taken the form of separate sovereignties — for Palestinians on an ever-shrinking territorial basis — rather than participation within inclusive political structures, as is the case in post-apartheid South Africa. Whether the goal is a single or binational state, a federation or a confederation, a sustainable solution would likely have to be based on recognition of individual as well as collective rights, based on distinct national identities.

A way forward?

In providing a historical account, my book cannot offer a recipe for future progress in the Palestinian struggle. But it is possible to identify lessons from the South African experience, and three in particular stand out.

The first is the need for mass mobilization inside the country as the central force applying pressure on the regime and pushing for change, encompassing workers, students, community members, religious congregations, NGOs, and other civil society structures. Armed struggle — usually carried out by militants based outside the country — played a role, and external solidarity added to the pressure, but the key role in the struggle was still undertaken by internal forces.

The second lesson is the need to organize on a non-sectarian basis to facilitate a move beyond the racial and ethnic divisions enforced by the state. One of the greatest assets of the ANC, which allowed it to become dominant, was its non-racial perspective that highlighted the central role of the oppressed black masses but created space for all who wished to work for democracy and justice, regardless of background. In this way, a small but important segment of the dominant group — young white people in particular, and to some extent a section of the business community — was encouraged to break ranks with the regime, undermine its legitimacy, and lend support to the mass movement.

The final lesson, which is somewhat in tension with the previous point, is the need to simultaneously frame specific appeals to constituencies usually organized on the basis of race, ethnicity, and religion, within a set of universal principles of justice, redress, human rights, equality, and democracy. This means combining the identity-based concerns of groups, which are essential for local mass mobilization, with broader concerns, which are essential for breaching group boundaries and mobilizing external support. This helps to make local struggle more inclusive, and facilitates global solidarity efforts.

To what extent the lessons of one specific case can be applied in another case remains, of course, an open question. But given the iconic status acquired by the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa, it might be able to offer a way forward. The ultimate decision with regard to which lessons are deemed valid, and how they could be applied in the Palestinian struggle, remains in the hands of those operating on its frontlines.