The uproar by Jewish establishment figures over Alexander’s New York Times essay in support of Palestinian rights echoes the reactions of white Americans to the Civil Rights Movement decades ago.

Michelle Alexander’s powerful New York Times essay on Saturday (“Time to Break the Silence on Palestine”), ahead of the commemoration of Martin Luther King Jr. Day, was arguably a milestone for the Palestine movement in the U.S.

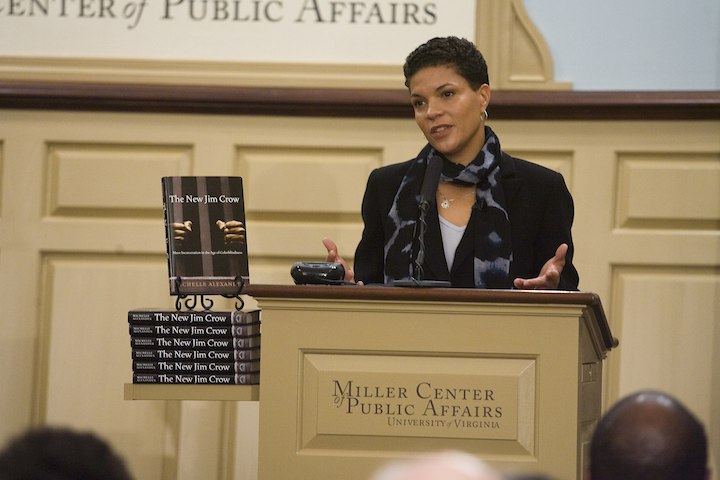

First, for who wrote it: Alexander, the author of the seminal book The New Jim Crow, is a renowned lawyer and public intellectual respected for her activism and scholarship on racism in the U.S., who cannot easily be dismissed as “fringe.”

Second, for where it was written: in a leading mainstream newspaper, which more frequently features op-eds by Israel advocates like Bari Weiss, Matti Friedman, Bret Stephens, Shmuel Rosner, and even officials like Naftali Bennett.

Third, for when it was written: Alexander is the latest prominent Black American in recent months to vocally express — and be targeted for — her solidarity with the Palestinian people, after others like Tamika Mallory, Marc Lamont Hill, and Angela Davis faced similar public outrages and disavowals.

And fourth, for why it was written: to challenge the widespread fear of backlash, held by many progressive Americans, for publicly criticizing Israel and speaking up for Palestinian rights.

The uproar over Alexander’s essay came swiftly from Jewish establishment groups and figures. Some of them are worth reading in full, if only to witness the hysteria and chutzpah of telling a Black woman how to remember one of the most significant African-American leaders in history, or how to interpret her knowledge of injustice:

- The Anti-Defamation League (ADL): “We have great respect for Michelle Alexander & her path-breaking civil rights work, but her piece on the complex Israeli-Palestinian conflict is dangerously flawed, ignoring critical facts, history & the shared responsibility of both parties to resolve it.”

- The American Jewish Committee (AJC): “MLK’s memory is not a moral cudgel to wield against any cause or country you disapprove of. Michelle Alexander’s op-ed is a shameful appropriation. We all have a long way to go to reach the mountaintop. There’s no need to take potshots at democratic Israel.”

- David Harris, CEO of AJC: “Michelle Alexander’s piece: in essence, calls for #Israel’s end / approvingly cites extremists / invokes support of #MLKJr w/no factual basis / ignores Israel’s search for peace since ’48; nature of Hamas; terrorism; Jewish refugees from the Arab world.”

- David Friedman, U.S. Ambassador to Israel: “Michelle Alexander has it all wrong in today’s @NYT. If MLK were alive today I think he would be very proud of his robust support for the State of Israel. An Arab in the ME [Middle East] who is gay, a woman, a Christian, or seeking education & self-improvement can’t do better than living in [Israeli flag].”

- Michael Oren, Kulanu MK and former Israeli ambassador to the U.S.: “Ambassador Friedman is right but Israel has to take serious steps to defend itself. By equating support for Israel with support for the Vietnam War and opposition to MLK, Alexander dangerously deligitmizates [sic] us. It’s a strategic threat and Israel must treat it as such.”

Predictably, these establishment figures are attempting to re-enforce the parameters of “acceptable” conversation on the conflict. As far as they are concerned, there is no such thing as a legitimate moral stance in support of Palestinian rights; the only things Palestinians produce are rockets and racism, and anyone who associates with their cause are either misguided or anti-Semitic.

It is especially ironic that those accusing Alexander of manipulating King’s legacy are also known for claiming, among other things, that using nonviolent tactics such as boycotts against Israel is racist, discriminatory, provocative, and/or unhelpful. King, and the Civil Rights Movement as a whole, were accused of the same during their campaigns of civil disobedience in the 1950s-60s.

As Jeanne Theoharis recounted in TIME this month, the U.S. government, the FBI, and local police forces used heavy surveillance, brutal force, and criminal indictments to undermine King and other Black leaders, viewing their activities as “dangerous,” “demagogic,” and “treasonous.” Polling data and media responses at the time further show that, far from being revered, the Civil Rights Movement was in fact “deeply unpopular” among the white American majority both in the South and the North:

Most Americans thought it [the movement] was going too far and movement activists were being too extreme. Some thought its goals were wrong; others that activists were going about it the wrong way – and most white Americans were happy with the status quo as it was. And so, they criticized, monitored, demonized and at times criminalized those who challenged the way things were, making dissent very costly.

This precisely describes the conditions of the Palestine movement today. Not only are Palestinian rights demands often viewed as extreme in the American public discourse (particularly the right of return), but opposition to Israeli policies face an aggressive political and legal infrastructure designed to quash it. These include new federal and state laws aimed at criminalizing BDS and conflating criticism of Israel with anti-Semitism.

Moreover, the frequent portrayal of Israel as a victim of Palestinian oppression, or that both sides share equal responsibility, is a fallacy disguising the gross asymmetry of the conflict. Explaining why it was disingenuous to tell Black Americans to do more to overcome their inequality, King once told a reporter “it’s a cruel jest to say to a bootless man that he ought to lift himself by his own bootstraps.” It is just as disingenuous to say that Palestinians have bootstraps to lift while they are subjected to exile, occupation, blockade, discrimination, and silencing of dissent.

As Alexander noted, King was an open supporter of Israel and Zionism in his time. However, it became increasingly difficult for him to reconcile that position with the universal values he promoted. Today, it is even clearer that his belief in justice, equality, and restitution for people under oppression – demands that are at the heart of the Palestinian cause – are antithetical to Israel’s goal of preserving Jewish superiority, and to its view of Palestinian nonviolence as equivalent to violence.

It is this realization that has led many Black American activists today – who have followed, built on, and transformed King’s legacy – to include Palestinian rights in their struggle for global justice. As Alexander wrote, Israeli practices have become inescapably “reminiscent of apartheid in South Africa and Jim Crow segregation in the United States,” and as such, require progressives to be consistent in the values they claim to uphold. The fact that a person like Alexander is adding her voice to this growing movement could further widen the doors for others to follow suit.

Though it is impossible to know what King would believe today, one could guess that he may have been taken aback by how similar the reactions to the Palestinian cause are to white America’s reactions to his own. Despite what Alexander’s critics claim, the real betrayal of King’s legacy is to think that Palestinians ought to remain subservient to Israel’s supremacist demands, as if they don’t deserve the same rights King fought to achieve for his own people.