Every Israeli national election brings with it the same public discussion about Israel’s Mizrahi communities and their alleged support for the right, and the ruling Likud party more specifically. Many among the left in Israel regularly hypothesize about the reasons so many Mizrahim — Jews with origins in Arab or Muslim countries — vote for right-wing parties, but often end up either missing the mark completely or recycling racist stereotypes.

So how is one to understand this choice? The main context of the question is the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. I will not pretend to provide a full and thorough answer to the question, but instead will provide examples to show how Israel’s decades-long policies of discrimination and marginalization of the Mizrahi public by the Israeli Ashkenazi establishment has caused many to find an answer to economic hardship in the nationalist camp.

If we understand the history of the Mizrahi struggle — and its suppression by the camp most closely associated today with the Israeli peace movement — from a political-economic perspective, we will better understand how Mizrahim have found themselves in realms most often associated with the nationalistic right. More importantly, such an analysis allows us to understand precisely why the right has given Mizrahim an answer to their economic hardships that stemmed from Ashkenazi supremacy in Israel’s political and economic arena.

Land, housing, and settlements

From its very beginnings, the Zionist movement’s historic struggle over land laid the infrastructure for the hierarchy of ethnicities and class in Israel. The 1948 war was the culmination of this struggle. After the expulsion and flight of the Palestinians — and the prevention of their return — Israel’s government and its Zionist institutions took over the vast resources that were left behind by the refugees. At the end of the war, only 13.5 percent of the country’s land was owned by the state, but through a rapid expropriation campaign, Israeli institutions took over most of the land. The immediate effect of this policy was, of course, the dispossession of the Palestinian people from their assets and homeland.

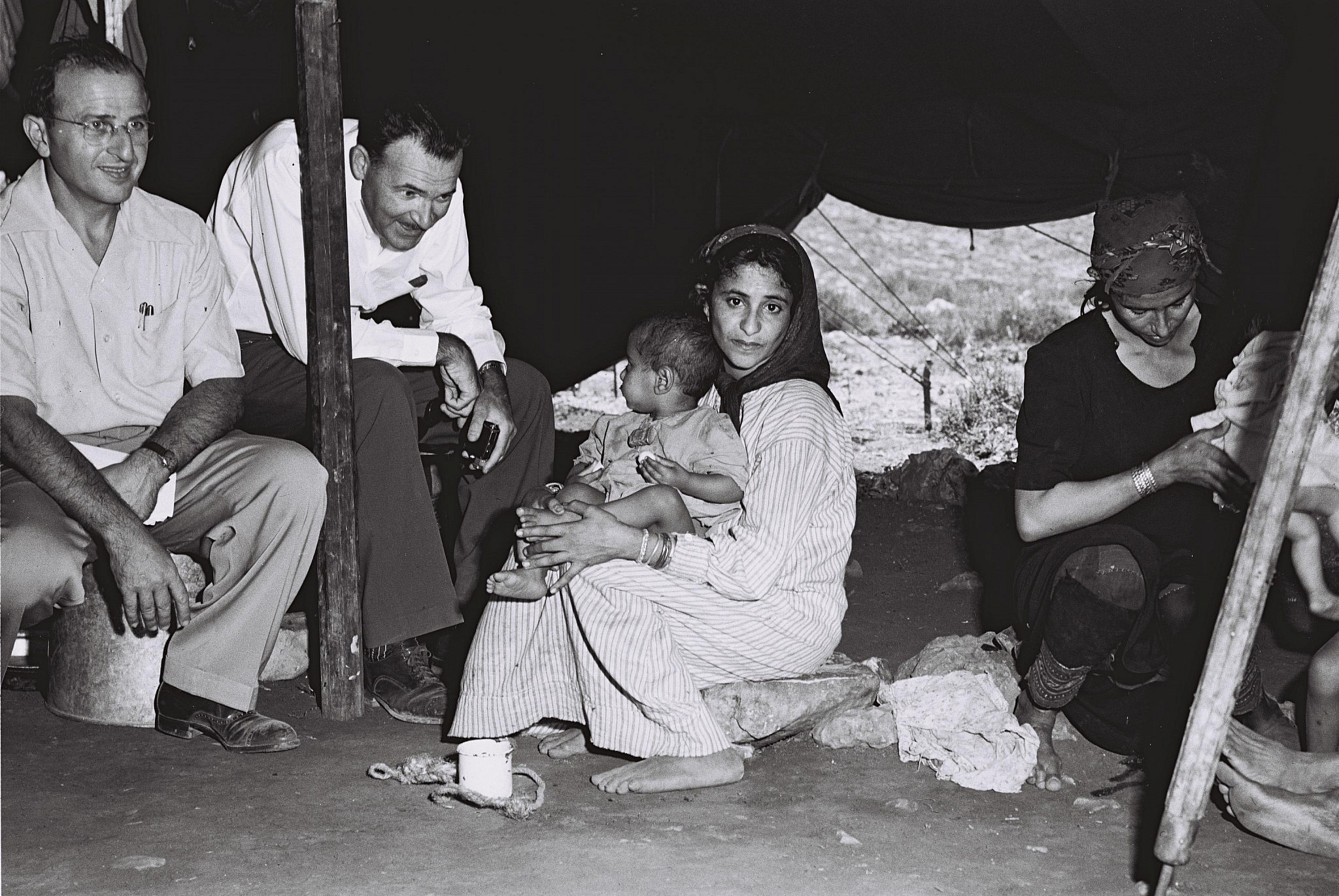

The distribution of Palestinian land among Jewish Israelis reflected a hierarchy along ethnic lines, between “veteran” Ashkenazim and newly-arrived Mizrahi immigrants who came to Israel after the war. This is also precisely how class differences were embedded into the fabric of Israeli society: an Ashkenazi elite with the privileges of housing and land as opposed to a disenfranchised Mizrahi population. Most of the Jewish communities that came from North Africa, particularly Morocco, were settled outside the urban center of the country, where Israel settled mostly Ashkenazi immigrants.

Protocols from meetings of the Interior Ministry and the Jewish Agency at the time reveal the way government officials viewed Mizrahim. North Africans, said the officials, could be sent to the frontier regions, while Polish immigrants — among whom were professionals, they claimed — should be given housing in the center of the country along the coast. The government hardly gave any land reserves to the dilapidated development towns that were built in far-flung regions of the country for North African immigrants, often on Palestinian land, as well as the Arab communities that remained after 1948. Regional councils, however, were home to kibbutzim, moshavim, and other forms of settlement associated with the Ashkenazi elite that founded the country.

Moreover, the distinction between areas in which Jewish ownership over Palestinian land was “formalized” in cities such as Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, and places where residents were deemed “invaders,” was similarly aligned to the distinction between Ashkenazim and Mizrahim. While kibbutzim, where most residents were of Ashkenazi descent, made use of admissions committees to ensure separation in housing, lower-class Mizrahim were forced into derelict public housing.

From the 1950s on, the Mizrahi struggle put the institutional racism of Mapai, the establishment political party and precursor to today’s Labor Party, in its crosshairs, demanding immediate remedy to the difficult situation of Mizrahim in Israel. A document published by The Union of North Africans — which led to the uprising by the Mizrahi residents of Haifa’s Wadi Salib neighborhood in Haifa in 1959 against the slum-like conditions they were forced to endure — demanded the government provide “humane housing for every family, the immediate elimination of all the Ma’abarot [government-run transit camps for new immigrants], the elimination of slums, and housing for bachelors,” among other demands. They also called on the government to provide adequate education for all, put an end to discrimination, stop ethnic segregation when it came to religious matters, end the military government that ruled the lives of Israel’s Palestinian citizens, guarantee freedom of speech, and more.

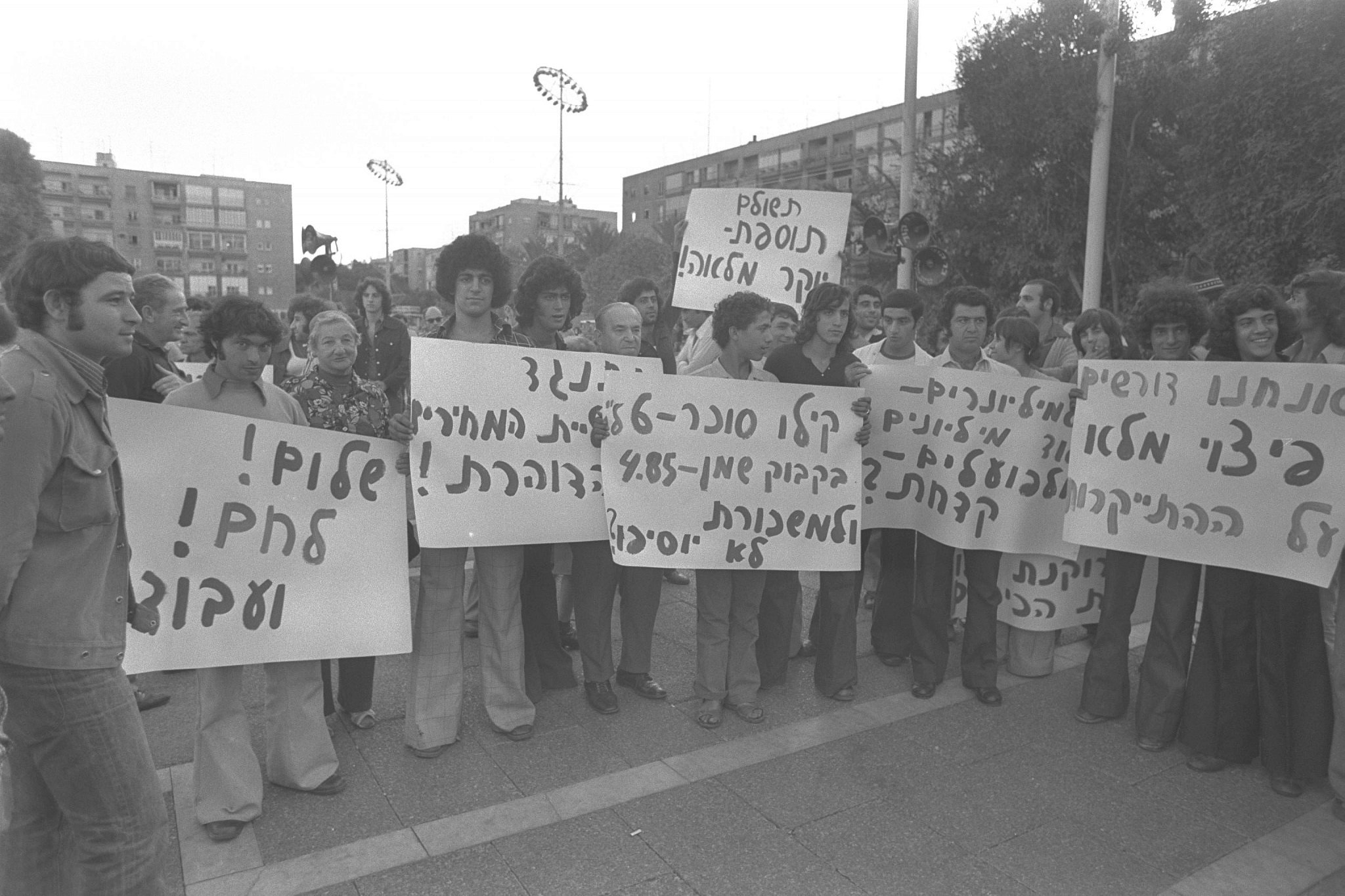

More than a decade later, the Israeli Black Panthers, who emerged from the neighborhood of Musrara in Jerusalem in 1971, spoke about “slums” to describe the housing crisis plaguing Israel’s Mizrahi public. They called on the government to dismantle the “ghettos for blacks” in the city. Activists in Jerusalem’s Yemin Moshe neighborhood complained that Mizrahi residents deemed “intruders” were being evicted from their homes and replaced by rich Ashkenazim. In this way, Mizrahi activists were actively defining their politics in left-wing terms of equality and human rights.

That is why the connection between the rise of Likud to power in 1977 and the resistance of the Mizrahi public to Ashkenazi material privileges — which marked the first 30 years of the state — are commonly, and narrowly, viewed through the prism of a historical resentment toward Mapai. One must consider the resentment of large swaths of Mizrahim against the Israeli left in this context of decades of institutionalized racism, the kidnapping of babies, and the spraying of new Mizrahi immigrants with DDT pesticide.

While these aspects are important, they do not tell the entire story. It is important to remember that Likud strengthened the socio-economic position of the Mizrahi public. Israeli historian Danny Gutwein claims that the relatively large number of Mizrahim who vote for the right is a product, among other things, of the way in which the settlement enterprise in the West Bank and Jerusalem compensated Israelis with the dismantling of its welfare state in the 1980s. In this way, Gutwein argues, Likud’s policies beyond the Green Line helped boost Mizrahi class position.

It is true that the welfare settlements provided the Mizrahi public with a solution to their economic problems. Yet despite Gutwein’s claims, the establishment of welfare settlements was not the result of the powerlessness of an Israeli welfare state that no longer exists, since real and equitable social welfare never existed in Israel in the first place. The main force propelling the building of welfare settlements beyond the Green Line are the socio-economic gaps between Ashkenazim and Mizrahim, the product of a regime of privileges for the former that was put in place before the 1967 occupation and gave rise to what we now call the Mizrahi struggle. The bounty of Palestinian land and resources was unequally distributed inside ‘48 lines, where Ashkenazim enjoyed privileges vis-à-vis land and housing, yet beyond the Green Line one could find new bounty, backed by government loans and subsidized housing, which, for the first time, benefitted Mizrahi families. This is how a significant portion of Israel’s Mizrahi public was able to find its footing.

Both Ashkenazim and Mizrahim benefitted from the dispossession of Palestinians at different stages of the Judaization of Palestine. While the “gains” of 1948 benefitted the Ashkenazi public, the Mizrahim found their solution to the housing crisis in the welfare settlements beyond the Green Line in Jerusalem and the West Bank. Each of these groups has their own political and economic interests. It is no wonder, then, that a group like Peace Now, which is affiliated with the Ashkenazi elite, will monitor settlement building beyond the Green Line but will never speak about the connection between the dispossession of the Palestinians in 1948 and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Education and employment

When it comes to education and employment, Israel’s regime of ethnic discrimination and segregation has pushed Mizrahim into the arms of the security establishment. In 1945, Eliezer Riger, one of the foremost advocates of vocational schooling who would later become inspector general of Israel’s education system, spoke about the necessity of segregation between Mizrahim and Ashkenazim in education: “Pre-vocational [education] leadership could bring a special blessing to the Oriental population, after all… the Oriental children, at least most of them, do not know how to appreciate simplified learning and cannot derive actual uselessness from non-practical education.” Zalman Aren, who was minister of education at the time, advocated a similar worldview: “I hold academic high schools in high esteem, but I have no doubt that the conditions of the state at this stage there is still preference for vocational schools. I wouldn’t want the development towns to stick to this kind of snobbishness and put a child in a high school that would damage him.”

The education system, until this very day, uses a policy of tracking students, placing many Mizrahi teenagers in vocational schools, while Ashkenazi students most often are sent to regular high schools. This policy clearly has a far greater impact on the educational prospects of Mizrahim, preventing many of them from continuing in academia.

According to a 2015 report by the Adva Center, an Israeli progressive think tank that monitors social and economic developments, Israel’s two largest vocational school networks, ORT and Amal, are mostly located in Israel’s geographic and economic periphery. Out of the 159 schools in the two networks, 113 (71 percent) are located in areas on the low end of the socio-economic spectrum, including 35 in Arab localities, 43 in development towns, and 35 schools in other localities. Moreover, a new study by Yanon Cohen, Noah Levin Epstein and Amit Lazarus on education among third-generation Israelis found that university or college graduation rates are around 20 percent higher among Ashkenazim when compared to Mizrahim.

The barriers to education have pushed many working class Mizrahim to look for employment opportunities with the Israeli army and other security forces. Israeli sociologist Prof. Orna Sasson-Levy explains how military service, even in low ranks, can provide economic opportunities for Mizrahim:

“As students in vocational schools, most of them without a high school diploma, most of the soldiers in these positions do not see themselves continuing on to higher education, with their physical labor power and the profession they acquired in high school may be the main resources they have to secure themselves economically, which is why it is important for them to develop the resources available to them from an early age […] Soldiers who continue to serve for a number of years on a professional basis also explain this through mainly economic considerations. They examine the military by standards usually reserved for a workplace such as the opportunity to receive professional training, social benefits, medical care, dental care, and more.”

Prof. Yagil Levy shows how the army could potentially help bolster one’s socio-economic class. His book, Israel’s Materialist Militarism, analyzes how the army has helped validate the social demands of Mizrahim through service in the army. While secular Ashkenazim began leading a process of de-militarization and looked for other socio-economic prospects, Levy found that groups on Israel’s periphery began using the army to fulfill their social and economic interests.

In addition to these studies, the high proportion of Mizrahim working in the police or the Israel Prison Service can be explained by the fact that in the absence of gainful employment — which requires higher education — working for the security forces offers stable economic conditions. This kind of work can serve as a refuge from a crisis of education and employment, just as welfare settlements were used by many as a refuge from a housing crisis inside Israel. In both housing and education/employment, the processes can be explained in light of class differences between Ashkenazim and Mizrahim. Thus, realms that are generally seen as right wing, nationalist, or hawkish vis-à-vis Palestinians — settlements beyond the Green Line or Israel’s security forces — are treated as a socio-economic anchor by Mizrahi communities in Israeli society.

The entrance of Palestinian day laborers from the occupied territories into the Israeli labor market after the occupation of 1967 has also played a key role in the elevation of Mizrahi socio-economic status, according to a 1987 study conducted by Noah Levin-Epstein and Moshe Semyonov. They showed that in 1969, around 42 percent of immigrants from Asia and Africa were employed in non- or semi-professional jobs; by 1982 that number dropped to 25 percent. Levin-Epstein and Semyonov note that “due to the concentration of Arabs of the occupied territories in a small number of occupations at the bottom of the occupational ladder, not only are they not perceived as a threat to most Israelis, but in many cases are even referred to as ‘liberators’ from ‘despised and unforgiving jobs,’” that most Israelis no longer had to work.

In his 1983 book “In the Land of Israel,” Israeli author Amos Oz traveled to the development town of Beit Shemesh, where he spoke to a local resident about what peace with the Palestinians might mean for Mizrahim:

“If they give back the territories, the Arabs will stop coming to work, and then and there you’ll put us back in the dead-end jobs, like before. If for no other reason, we won’t let you give back those territories. Not to mention the rights we have from the Bible, or security. Look at my daughter: she works in a bank now, and every evening an Arab comes to clean the building. All you want is to dump her from the bank into some textile factory, or have her wash the floors instead of the Arab. The way my mother used to clean for you. That’s why we hate you here. As long as Begin’s in power, my daughter’s secure at the bank. If you guys come back, you’ll pull her down first thing.”

For residents of development towns, Likud rule and control over the occupied territories serve as a guarantee against the threat of Mizrahim returning to a lower socio-economic status and being forced to compete with Palestinian citizen of Israel over jobs and resources. This is an additional example that shows how material conditions, borne of the power relations between different groups in Israeli society and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, led to a Mizrahi “alliance” with Likud.

The competition between Mizrahim and Palestinians in the labor market is not a product of the imagination of the Beit Shemesh resident — it is the product of the real political conditions of the Mizrahi public in Israel. Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben Gurion, said “We need people who were born as laborers. We must pay attention to the local element among the Oriental communities, the Yemenis and the Sepharadim, whose quality of life and demands are lower than a European laborer and can successfully compete with the Arabs.”

Our boys in Likud

Yet another example of how the class interests of the Mizrahi public were realized through its support for the Israeli right can be seen in the high proportion of Mizrahi members that make up the Likud party. One particularly salient moment in 2002 shows precisely why. During a rousing speech in front of hundreds of members of the Likud Central Committee, former Education Minister Limor Livnat, asked the crowd rhetorically whether the political leadership of the party had been “elected to hand out jobs.” Expecting the crowd to overwhelmingly respond in the negative, Livnat was taken back when committee members resoundingly chanted that, yes, they were expecting the party to give them something in return for their undying support.

This moment perfectly encapsulates how Mizrahi support of Likud is part of a deal: Mizrahim and Central Committee members will support the public only in exchange for offices in the corridors of power of the Israeli regime. Thus, Mizrahi interests coalesced around endless Likud rule in the form of political appointments, workers’ unions, and local authorities.

One must understand the historical context in which the Likud Central Committee became a hub of Mizrahi activism. When Mapai was in power, the party engaged in what is known as protektzia, or the handing out of favors, to party members. That meant that the best jobs and housing would remain in the hands of party apparatchiks. It also meant that many Mizrahim remained outside that circle of nepotism. Likud’s Central Committee can be seen as a response by the Mizrahi public as compensation for Ashkenazi privilege that resulted from Mapai’s control over state bodies and institutions.

Confronting Ashkenazi privilege

The election of Menachem Begin in 1977 created a new ethno-national discourse, one which mobilized the Israelis on the socio-economic margins of society to support the right. In 2003, Prof. Sasson-Levy published a study based on interviews with Israeli soldiers from lower-class backgrounds. She found that soldiers who come from poor socio-economic backgrounds more vehemently express right-wing views. From Sasson-Levy’s research:

“[Their] right-wing views emerge from the ethno-national discourse as a form of compensation for their class marginalization in Israeli society, as it allows them to present themselves as belonging to the heart of the Israeli consensus by nature of them being Jewish.”

This argument can apply to the wider Mizrahi public in Israel. Unlike the historic leaders of Mapai, who scorned anything that even faintly resembled Mizrahi and Arab culture, Menachem Begin was able to bring Mizrahim into the fold of Israeli identity by broadening its definition to include all Jewish Israelis, rather than only those who looked and sounded like the party elite. In his famous “Riffraff Speech” from 1981, Begin responded to racist and disparaging comments made by Dudu Topaz — one of Israel’s most famous television personalities and a member of the liberal Ashkenazi camp — about Mizrahi soldiers, by promising to do away with the hierarchy between Ashkenazim and Mizrahim in the Israeli army. This is how the dynamics between Ashkenazim and Mizrahim led the latter to look for solutions to their socio-economic hardships in the hawkish policies of the Israeli right. Begin’s vision, which openly embraced Mizrahi Jews, would only further entrench the racial hierarchy between the country’s Jewish and non-Jewish citizens.

Despite claims by left wingers that the Mizrahi public votes against its own interests, it is worth taking stock of the ways in which a set of core Mizrahi interests have come into existence under Israel’s right-wing rule. It appears as if those who believe Mizrahim would be better off voting for the Israeli left in its current form — primarily Ashkenazi and upper-middle and upper class — are unaware, or do not want to confront the privileges Ashkenazim have enjoyed since the founding of this country. Without a real discussion of this aspect of the Israeli regime, we will be unable to begin a process of reconciliation and repair, both inside the Jewish public in Israel and within the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.