“Bibi: My Story,” by Benjamin Netanyahu, Threshold Editions, 2022. Quotes in this piece are taken from the Hebrew version.

In the lead-up to general elections, Israeli politicians sometimes conduct informal meetings with members of news desks. In 2008, several party leaders visited Maariv, the daily where I was working as an editor. We would meet in the conference room; the main value of the events was the stream-of-consciousness, free-flowing conversations that sometimes developed with leaders who, at least when on camera, rarely went off script. Ehud Barak impressed everybody in the room with his strategic analysis and command of details. A week later, Avigdor Lieberman was politically shrewd and intellectually shallow.

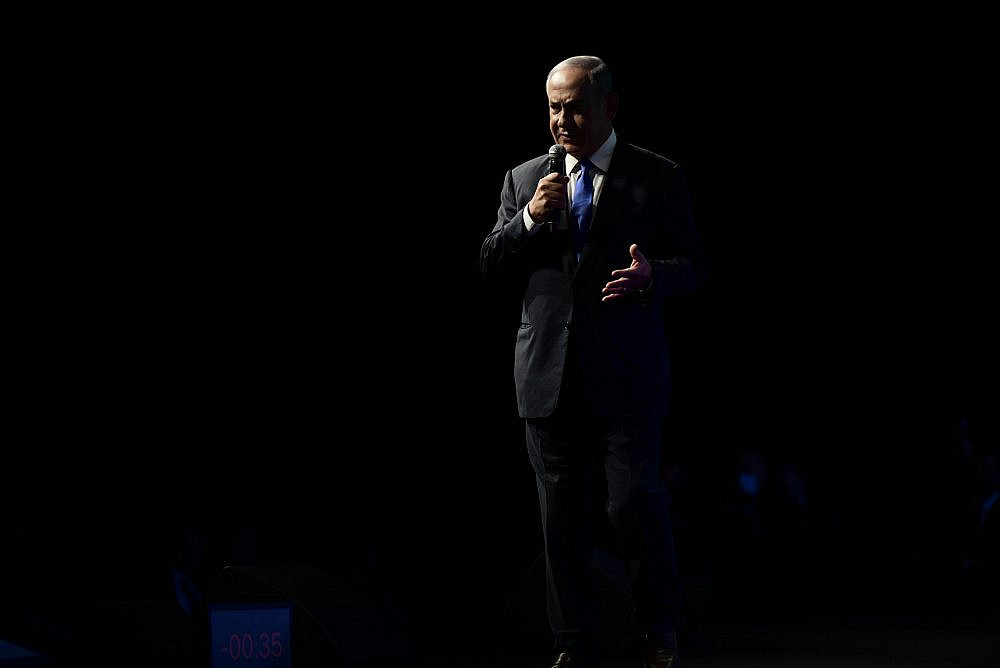

Finally, Benjamin Netanyahu arrived. Almost a decade after the defeat that ended his first term as prime minister in 1999, and a couple of years after suffering his worst political loss, when his Likud party won an all-time-low 12 Knesset seats, Netanyahu was on the verge of a long-awaited return to power, running head-to-head against Kadima’s Tzipi Livni.

In a room full of skeptical journalists, many of whom opposed and even openly despised him, Netanyahu made good on his reputation as an excellent communicator. He spoke rather than lectured, and seemed honest and engaging. His sense of humor humanized him — though one comment he made, about the way in which economic growth brought down the Arab birth rate, thus helping to maintain a Jewish majority among Israeli citizens, made some of us move around uncomfortably in our chairs.

Netanyahu mostly discussed the economy, a topic he clearly enjoyed talking about, having served in his last ministerial role, from 2003-2005, as finance minister. But when the time came for Q&A, the paper’s editor-in-chief immediately cut to the elephant in the room. “What about the Palestinians?” he asked.

This was only a few short years after the end of the Second Intifada, and a new reality was still taking shape: Hamas had taken over Gaza, while Prime Minister Ehud Olmert was discussing the two-state solution with Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas. The Palestinians were The Issue. Yet standing before us, Netanyahu had very little to say beyond criticizing the Olmert government’s ideas and solutions and saying Israel should be more forceful in arguing its case. When pressed to present his own plan, he described something like an enhanced Palestinian autonomy in the West Bank, with Israel maintaining control over the Jordan Valley. As he spoke, I thought about how the man who made a career out of opposing the Oslo Accords, was effectively suggesting turning them into a final-status agreement — a slightly improved version of the status quo. It wasn’t just ironic; his thinking seemed out of touch with reality. “Unbelievable,” the paper’s editor summed it up when Bibi left the room.

“Bibi: My Story,” Netanyahu’s autobiography, written during the nine months he spent in the opposition and published just ahead of this week’s Israeli election, feels in many ways like a continuation of that meeting in 2008. This will be the fifth election Israel has seen in four years — an unprecedented political crisis that revolves entirely around Netanyahu. The polls are as tight as can be; victory could be determined by several thousand votes going to one small party or another. Accordingly, Bibi’s memoir is partly a campaign document, and partly aimed at cementing his legacy.

Netanyahu’s personal fate still hangs in the air, but his place in history is assured. He feels vindicated, proven right by the events of recent years. But while he has succeeded in making mainstream what previously seemed implausible, and rewriting the vocabulary of Israeli political discourse, his stubborn avoidance of the Palestinian issue means that it will continue to define the contours of Israeli politics long after he is gone.

Sidestepping the Palestinians

In his memoir, just like 12 years ago, any discussion of the Palestinians is put forth solely in order to refute, rather than to paint a vision of the future. Referring to the Palestinians who live within ‘48 borders as “Arabs,” he insists they are full, equal citizens, while those who live in the West Bank and Gaza ”run their own lives” and are “in no way governed by Israel.” If apartheid exists, Netanyahu writes, it is inside the Palestinian Authority, which doesn’t allow Jews to purchase land within its territory.

The book is riddled with these kinds of half truths and facts deprived of context. As Netanyahu knows all too well, Israel does settle Jews inside Palestinian Hebron and the Palestinian neighborhoods of Jerusalem, while Palestinians under occupation can’t even travel freely without an Israeli permit, or even dream of living in Jewish cities or settlements. Even if a Palestinian marries an Israeli citizen, they would need to live outside the country, or separately. And as for “running their own lives,” Palestinians’ borders, exports, imports, roads, regional zoning plans, currency, electro-magnetic frequencies, air space and more are all controlled by Israel.

Throughout his long years in power, Netanyahu stayed true to his promise: he maintained the occupation, expanded settlements, and argued his case forcefully. But something changed during this period: today, nobody can dismiss his version of reality as “unbelievable.” Bibi has turned his worldview into the common denominator of Israeli politics. His idea of a final status agreement — annexing the settlements while keeping Palestinians in Bantustans scattered between them — has even turned into a formal peace plan put forward by the Trump White House.

Netanyahu admits in his book that he prefers American administrations not to deal with the Palestinian issue at all; “messianism” is the term he reserves for this project, accusing those who pushed for a two-state solution of “chasing Nobel Prizes.” His opposition to repeated peace efforts led by both Bill Clinton and Barack Obama is for him a source of pride, not a matter for soul-searching, which rarely exists in his book. He even blames the Bush and Trump administrations for focusing too much on the Palestinians.

For years, Netanyahu fought against the notion that an agreement with the Palestinians is the key to Israel’s acceptance in the Middle East. Indeed, following the Arab Spring, several Arab dictatorships have warmed up to Israel — some have even signed normalization agreements with it. Netanyahu feels almost gleeful when he quotes former Secretary of State John Kerry, who claimed in 2016 that “there will be no separate peace between Israel and the Arab world… without the Palestinian process and Palestinian peace.”

“We bypassed the Palestinian issue and got four diplomatic breakthroughs,” Netanyahu writes. “There you have the real ‘New Middle East,’ built on power.” His success in popularizing this notion is striking: nobody in the Biden White House wants to deal with the Palestinians. Yet he avoids the most important reason for pursuing a final-status agreement: not geo-politics, but the nature of the regime that emerged once the occupation became permanent. On that, Bibi offers very little substance.

‘A moderate conservative’

Written in English, Netanyahu’s autobiography seems at times to be directed at a foreign, mostly American audience. It is a lively book, full of anecdotes, and is mostly interesting to read. He spends long pages discussing his dealings with American presidents; confrontations with Obama were, he says, the greatest challenge of his life. He compliments the former Democratic president for his passion and political skills, but believes Obama judged events according to “a neo-colonial worldview.” He even accuses the president who toppled the Libyan regime, escalated the war in Afghanistan, and sent U.S. forces to kill Osama Bin Laden in Pakistan, a U.S. ally, of believing only in “soft power” — mainly because he refused to threaten Iran with war.

The Trump years, Netanyahu says, were the best for Israel. He is also fairly generous with Vladimir Putin’s version of realpolitik, while avoiding mentioning the war in Ukraine altogether.

There are only a few occasions of true self-revelation in the book — a panic attack ahead of his 2015 speech before Congress is one rare such moment — and even less reflection or self-doubt. His errors, from confessing to an extramarital affair on television to his bet on Mitt Romney in the 2012 U.S. presidential election, are left out. In geopolitics, as in his personal life, Netanyahu never felt sufficiently secure or at ease to let go of his narrative. His dog-whistle comments on “Arab voters heading to the polling stations in droves” in an attempt to topple his government in the 2015 election are explained as a matter of sloppy phrasing. He sees himself as a moderate conservative, and rejects the accusation that he fanned the flames ahead of the murder of Yitzhak Rabin (these pages read as if Netanyahu sees himself as the real victim of the affair). For obvious reasons, his political pacts with racists and nationalists are not mentioned — Netanyahu will need them again.

He has some kind words for the dead and defeated Shimon Peres, but not for other political rivals, and he is bitter when discussing the media or his legal troubles. No problem is of his own doing; conspiracies against him are everywhere. For Netanyahu, confrontation was always a feature, not a bug. He was ahead of his time: before he was elected, having good relations with the international community — and particularly the White House — was considered a political asset. Today, putting on a tough face and sticking it to the world seems to be in fashion, and not only in Israel.

In politics, Netanyahu always preferred to energize his base rather than wear the mask of a moderate, which would appeal to the center. Here, too, what once seemed novel and outrageous in his character is now the sign of the times. During his first term, and against the backdrop of the optimism and multiculturalism of the 1990s, Netanyahu’s tribalism seemed odd and misplaced; today it is almost a political cliche. This is now his main political challenge: when everybody thinks and acts like Bibi, he finally seems replaceable.

Creating the zeitgeist

Pundits see Tuesday’s election as a key moment in Israeli history: if Netanyahu and his coalition partners win an absolute majority, they promise to implement radical changes in Israeli institutions — from facilitating the nomination of their proxies to key positions, to placing limits on the courts’ ability to stop government actions or to prosecute politicians. This could help Netanyahu stay out of prison over the corruption charges that have dogged him these past years. It would be the most radical government Israel has known, in which Meir Kahane’s racist followers could receive cabinet positions. If Netanyahu loses, he could even find himself in prison. And, of course, there is always the possibility of deadlock and another election.

Yet, no matter his personal fortune in this election, Netanyahu has succeeded in transforming Israeli politics. He created a new political vocabulary that redefined the relations among Israeli Jews, and between them and the Palestinians. When Netanyahu’s opponents attack him for not toppling Hamas or for removing Israeli soldiers from parts of Hebron, they do so with phrases he himself invented and using talking points for which he was known. When he defends himself in his book, it is usually from his right flank, not his left.

Ideas such as demanding that the Palestinian leadership recognize Israel as a “Jewish state,” which was never part of the negotiations between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization, are now seen as an inherent element of any future deal; it has become mainstream political consensus that Jerusalem will never be divided; “leftist” has become a curse word; Kahanism has gone mainstream; and an end to the occupation seems like a fantasy even among its die-hard opponents. The unthinkable has become normal, and what was once deemed “common sense” now seems absurd, outdated, and, to many, dangerous.

Like most books written by active politicians, Netanyahu’s autobiography lacks intimacy, but there is something in its tone that feels so close to home, so familiar. The year 1996, when Netanyahu rose to power, was also the first time I voted in a general election. He has been prime minister for most of the years that have since passed, and even in his absence, Netanyahu continued to cast a large shadow over Israeli public life; it is no surprise that the two main political camps in Israel are no longer called “left” and “right,” but “Bibistim” (Hebrew for Netanyahu’s supporters) and “anti-Bibistim.”

Netanyahu’s prose is the zeitgeist, a language he created, and which will remain his main legacy after he is gone — befitting for someone who has, from an early age, been known as his country’s most adept public speaker. But like many great speakers, he used his gift to avoid problems rather than deal with them. Whether Netanyahu likes it or not, the unresolved Palestinian issue, rather than Iran, remains the single existential question plaguing Israel and Israelis. Indeed, it is The Issue. Once, there was, at the very least, an imagined resolution for it. Netanyahu did away with it. With or without him, we are all left staring into the abyss.