Forty years of land grabs, settlement expansion, and the building of a highway that is off limits to Palestinians. This is what is happening to Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib’s village.

By Dror Etkes

The West Bank village of Beit Ur al-Fauqa made headlines over the weekend, after Democratic Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib announced she would not accept Israel’s offer for a “humanitarian visit” to see family, and particularly her aging grandmother.

Beyond Tlaib’s personal story, however, is the story of a village that has seen decades of land grabs for the purpose of Israeli settlement expansion and the construction of a bypass road, which Palestinian residents of the West Bank have been banned from using for nearly two decades.

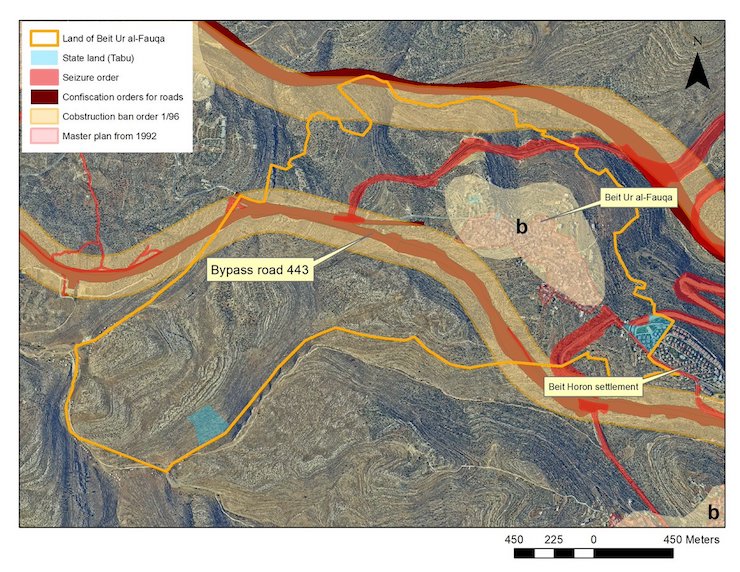

Beit Ur al-Fauqa is a relatively small Palestinian village located approximately nine kilometers west of Ramallah and seven kilometers east of the Green Line. According to the 2017 Palestinian census, the village has 1,049 inhabitants. A British land ownership survey, conducted during the years of the Mandate, shows the village land is comprised of 943 acres.

As a result of the Oslo Accords, 101 of those acres became part of Area B, under Palestinian civil administration and full Israeli military control. Another 3.5 acres of land were included in the village’s Israeli-approved master plan from 1992, granting it a total of 104.5 acres — 11 percent of the village’s total land — available for Palestinian construction.

Luckily for the inhabitants of Beit Ur al-Fauqa, their land was already fully registered before June 1967, when the West Bank came under Israeli occupation. At the time, only two plots of land in the entire village were registered as Jordanian state land in the general registry (Tabu).

This spared large tracts from the same fate as nearby villages Beitunia and A-Tira, where swaths of land were declared “state land” by the Israeli authorities and were automatically handed over to Israeli settlements. At the eastern edge of Beit Ur al-Fauqa lies one of the two parcels registered as Jordanian state land. This parcel was also taken by the Israeli authorities and allocated to the settlement of Beit Horon, which was established in 1977.

Yet the real story of Beit Ur al-Fauqa is not the settlement of Beit Horon but Route 443, a highway built through the West Bank in the early 90s to connect northern Jerusalem and its adjacent settlements to Israel’s coastal area.

To pave this road, the Israeli army confiscated 50 acres of the village’s land in the late 80s. Hearing that their land would be confiscated, landowners from Beit Ur al-Fauqa and the neighboring villages petitioned Israel’s High Court of Justice. The High Court would eventually dismiss the petition, accepting instead the IDF claim that the road would also serve the “local population,” who will be able to drive on it faster and more securely.

When the road was finally paved, 425 acres of Beit Ur al-Fauqa’s cultivated and grazing land were practically disconnected from the village, remaining southwest of Route 443.

What about an access road to these 425 acres or a tunnel under the newly-built highway? Not in the West Bank. Once the road was constructed, the villagers were forced to make a seven-kilometer detour to reach their land. It is no wonder that few bother to make the trip.

This wasn’t the village’s first encounter with the occupation’s land policies. In 1979, the IDF issued a confiscation order for 545 acres in the area; only a few acres were confiscated from Beit Ur al-Fauqa for a road that was supposed to be paved just north of the village. Luckily for the villagers, that road was never paved. In 1996, the army issued Construction Ban Order 1/96, preventing construction alongside roads in the West Bank, including Route 443 to the south of the village as well as the planned road to its north. The order included 113 acres of the Beir Ur al-Fauqa’s land.

At the end of 2000, as the violence of the Second Intifada was beginning to unfold, Palestinians were sporadically banned by the IDF from using Route 443. Following several cases of Palestinian gunfire at Israeli vehicles on the road, in which six Israeli citizens and one resident of East Jerusalem were killed, Israel entirely prohibited Palestinians from using the road in 2002.

Yet the IDF had officially committed to the High Court’s demand that Palestinians be allowed to use the road. For this, the army uses “temporary seizure orders.” Between 2005 and 2006, the IDF issued seizure orders for 30 more of the village’s acres in order to pave two “fabric of life” roads — an alternate network of roads and tunnels intended for Palestinian use only — that would serve as Palestinian bypass roads on Beit Ur al-Fauqa’s land.

It is true that Beit Ur al-Fauqa does not suffer the worst consequences of Israel’s occupation and its land grabbing enterprise. In many ways, it’s just “another village” — and that’s bad enough.

Dror Etkes follows Israel’s land and settlement policy in the West Bank.