The Arab Spring presents a conundrum for many liberal Jews. As liberals they feel compelled to advocate self-determination over tyranny and democracy over dictatorship. But as Jews they worry that the Arab dictators, particularly Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak, held down the lid on a seething Pandora’s Box of popular anti-Semitism. On the contrary, though, I would posit that anti-Semitism festered in Egypt as a result of Mubarak’s policies, and that it will naturally fade away if Egypt succeeds in making the transition to a more transparent, democratic society.

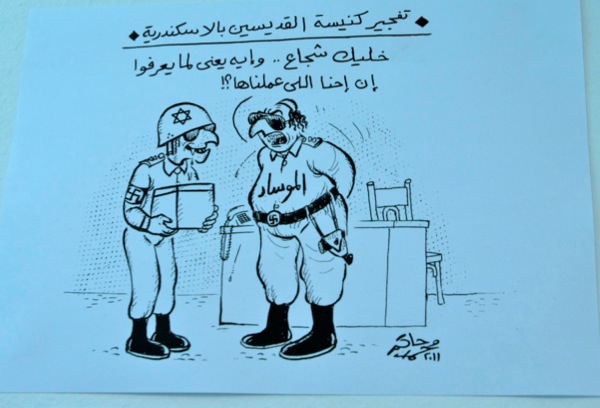

When anti-regime activists attacked and burned the Israeli embassy in Cairo in September, the violent images seemed to underline Jewish fears. It is also true that one hears quite a lot of old-fashioned anti-Semitic talk in Egypt — conspiracy theories about Jewish lobbies, Jewish bankers and Jews in the media. Amongst the secondhand books for sale by a sidewalk vendor at Tahrir Square last spring, I saw an Arabic translation of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. And an exhibition of political cartoons in downtown Cairo included some with caricatures of Israeli soldiers identified by their hooked noses, fang-like teeth and long, curly sidelocks.

But Mohamed Abla, the artist and political activist who curated the exhibition said, in answer to my question, “We show cartoons that we disagree with, too.” Those anti-Semitic caricatures, he explained, were published in pro-Mubarak newspapers that presented the Egyptian revolution as an anti-Egypt conspiracy cooked up between the unlikely allies of Israel, Hezbollah and the United States.

Amr El-Zant, an Egyptian physicist and a columnist for Al Masry Al Youm, Egypt’s best-known independent daily newspaper, describes Mubarak as an old-fashioned anti-Semite who thought that by having a close relationship with the Jews, some of their power would rub off on him. “He couldn’t understand why Israel failed to save him from the revolutionaries at Tahrir Square,” said El-Zant, a former diplomat’s son who was once a postdoctoral fellow at Haifa’s Technion Institute.

The deposed dictator played sly games to maintain his grip on power. He cultivated his relationship with the Israeli elite — the politicians, the army and the business tycoons — while manipulating popular opinion at home by blaming opposition to his rule on “the Jews.” He convinced Israelis that he was all that stood between them and a howling, bloodthirsty mob, but he only visited Israel once in all the 30 years he ruled Egypt — to give a eulogy at Yitzhak Rabin’s funeral. He prevented normal contact by having his dreaded state security service investigate, harass and even arrest Egyptians who applied for a visa to Israel or maintained contact with Israelis. This is why young Egyptians are careful to differentiate between opposition to the State of Israel, which is widely reviled, and anti-Semitism. They saw how the regime used anti-Semitism to stir up conspiracy theories and manipulate public opinion in order to maintain its grip on power.

I did not meet any Egyptians who had read the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. But I did meet many who had read Andre Aciman’s Out of Egypt, and Lucette Lagnado’s The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit — memoirs by Egyptian Jews who were forced out of the country during the Nasser era. Both titles were prominently displayed at several bookshops I visited in Cairo and Alexandria.

Amongst the politicians elected in Egypt’s first democratic elections, one still hears the occasional anti-Semitic remark. Fayza Abul Naga, a secular 61 year-old woman who is a holdover from the Mubarak regime, recently claimed that Freedom House, an American NGO that conducts research into democracy advocacy, was ‘a tool of the ‘Jewish lobby.”’

This is ugly and regrettable, but not, I think, insidious — and not because there are almost no Jews left in Egypt, but rather because Jew hatred is a relatively new, imported phenomenon that has little history in Egypt and does not seem to run very deep.

Take, for example, Cairo’s Shaare Shamayim Synagogue. It is a big, imposing building on Adly Street, in the heart of downtown, about five minutes’ walk from Tahrir Square. It is one of only two synagogues in Cairo still in use — I attended a seder there last spring. Under Mubarak, Shaare Shamayim was heavily guarded: Men in uniform checked the identity cards of visitors before passing them through a metal detector, while plainclothes officers stopped passersby from taking photographs. The message was clear: Without a strong security presence, the synagogue was vulnerable to attack. But there were no police on the streets for 15 days during the January 25 uprising. The synagogue was left completely unprotected. While the headquarters of the NDP, Mubarak’s political party, was set alight by protesters, as were other edifices associated with the regime, it never occurred to the protesters to attack the synagogue. The Israeli embassy, meanwhile, is halfway across town — but it was attacked, albeit several months after Mubarak resigned.

So does this mean that average Egyptians wants to cancel the peace treaty with Israel and go to war? No, not that either. They don’t like Israel and they would probably like to downgrade the diplomatic relationship, but no one wants war. Poll after poll shows that the average Egyptian wants stability. And war is the opposite of stability.

Hisham Kassem, a prominent Egyptian journalist and editor who founded Al Masry Al Youm, put it succinctly when he told me, “Ask the average Egyptian taxi driver what he thinks about Israel and he’ll probably say he hates it. Then ask him if he is willing to send his son to fight Israel, and he will shout ‘no way.’”

This op-ed was originally published in the Forward.