Content warning: The following article contains mentions of sexual abuse and suicide.

On a Friday morning at the end of December, Orthodox activists distributed hundreds of thousands of flyers throughout Israel featuring an arresting image: a young, terrified-looking girl, her mouth covered by the hand of a man wearing a bracelet reading “lashon hara, lo medaber elai.” (The phrase is a halakhic expression meaning, roughly, “evil speech doesn’t speak to me,” and which exhorts people not to speak ill of others.) The flyers, which were handed out in the street, posted in mailboxes, pasted on billboards, and pinned up in synagogues, also featured the slogan, “We all believe the victims,” provided support and resources for survivors of sexual abuse.

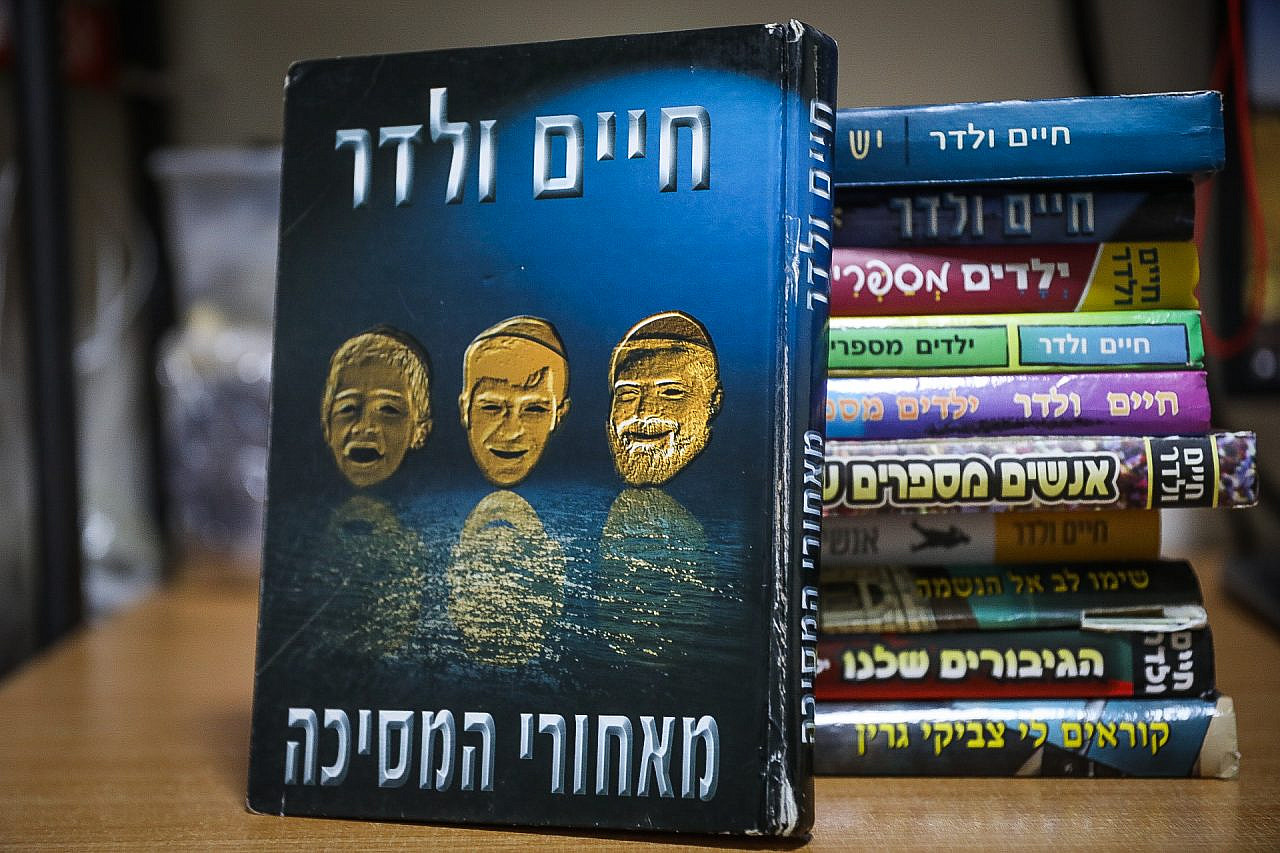

The flyers were part of a grassroots campaign in the immediate aftermath of the suicide of Chaim Walder, a Haredi Israeli educator, therapist, and children’s author who, until multiple allegations of sexual abuse came to light in November last year, had been a revered figure in Haredi society. The initial survivors’ testimonies all came from women, some of whom had been minors when he assaulted them; later, investigations also found that he had abused boys, and that he had blackmailed some of his victims into staying silent.

The testimonies led to some fierce condemnations within Haredi communities, with booksellers in Israel, the United States, and Europe removing his texts from their shelves, and Haredi media outlets in Israel pulling the plug on his contributions. In the wake of Walder’s death on Dec. 27, however, noted Haredi rabbis eulogized him and the charge was put forward that his accusers were guilty of murder through lashon hara. Days after Walder’s funeral, Shifra Horowitz, one of his victims, took her own life — unable, her friends said, to “bear the festival they made for him.”

The painful, and very public, conversation that erupted around Walder’s abuse — and about the response to the survivors’ testimony — is to some degree down to the specifics of the case: Walder’s profile and the ubiquity of his writing in Haredi homes; the denigration of his victims after his death; and the increasing interconnectedness of Haredi communities around the world, in part through access to social media. But the response this time around — in contrast to previous allegations of sexual assault by high-profile men in Haredi society — is also, according to two Orthodox activists and advocates who spoke to +972 Magazine, the result of years of tireless campaigning and organizing around the parallel issues of sexual abuse and silencing of survivors.

“There’s been limited change in the Haredi world, but the fact that the words ‘sexual abuse’ can be spoken aloud — that’s change,” says Asher Lovy, a survivor himself and the director of New York-based Za’akah, a non-profit that educates around child sexual abuse in Orthodox communities, provides resources to survivors, and pushes for state legislation that will protect people from such abuse. “And that wouldn’t have happened without years and years of survivors, and people from the outside, pressuring people on the inside to do something.”

And it was precisely the backlash to the support for Walder following his death that caused the greatest mobilization, says Pnina Pfeuffer, a Jerusalem-based social and political activist and the CEO of New Haredim, an umbrella outfit that organizes Haredi activists for social change, and which was involved in the grassroots campaign following the revelations about Walder. It was then that “all the work I’ve been doing over the past three years of networking, mobilizing, strengthening and bringing together social activists, erupted into this campaign and changed the conversation,” she tells +972.

Yet even with this progress, say both Pfeuffer and Lovy, there is much structural and educational work to be done on preventing sexual abuse, supporting survivors, and creating reliable avenues for reporting. In the following conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity, they share their thoughts on why this case feels different, what has changed and still needs to change, and the various Orthodox-led initiatives taking place on the ground in Israel and the United States.

There’s been a very public conversation going on within Haredi society about sexual abuse and silencing of survivors. It’s coming on the back of women’s testimonies regarding their abuse and exploitation by Chaim Walder, who was a highly respected Israeli rabbi and children’s author and educator —

Pfeuffer: He was not a rabbi. Every Haredi man above the age of 20 who’s married will have that title. And any woman who’s very learned and well-versed will not have that title. Just so you know!

Thank you for that correction. An Israeli children’s author and educator. To those on the outside of these communities, it might appear that the current dialogue is unprecedented. But it’s also not the first time that such revelations have come to light and prompted a reckoning within Haredi society. Does what’s happening at the moment feel different to you? And if so, why?

Pfeuffer: I think what’s different here is the celebrity status [of Walder] creating that type of reaction — the same as with #MeToo. People are always shocked and appalled when these things come to light, but [in this case] every other Haredi had a Walder book in their house, or had been sent to one of his day camps, or had some sort of interaction, at least with his public image. He also had very wide circles of personal friends in powerful places. We recently had [sexual assault revelations about] another Haredi celebrity, [Yehuda] Meshi-Zahav [the founder of the Israeli volunteer emergency response organization ZAKA], and the reason the reaction was different in his case was because he had a celebrity status outside the community. Inside the community he was not well-respected, but outside the community he had an image as an extreme Haredi who built bridges and became a Zionist.

Walder was really a nobody outside the community, but was a huge household name within it. Aaron Rabinowitz [who broke the Walder story] had a hard time convincing Haaretz to take on this piece, because they were like, ‘Who’s Chaim Walder?’ When it came out nobody was talking about it. And there were bots bought to defend him [on social media]. Our presence on social media was what really picked the story up, gave it continuing life, because the Haredi media was totally silent — as far as they were concerned, nothing happened. And then the second publication [of survivors’ testimonies] came out, and then obviously [Walder’s] suicide, followed by the official reaction of trying to silence the victims by saying it’s lashon hara etc. — that’s when all the work I’ve been doing over the past three years of networking, mobilizing, strengthening and bringing together social activists, erupted into this campaign and changed the conversation.

Lovy: We’ve had other cases of people in the Haredi world who have been abusers, and we’ve had camps split on whether or not people will believe the allegations. I’ve never seen in my lifetime people on their own — against the wishes of some of the rabbis in the community — going and burning books. That’s new, and there are a few things at play. Ten years ago, when [self-styled religious counselor] Chemi Weberman was arrested in Williamsburg for raping a girl he was providing unlicensed therapy to from the age of 12 to 15, the community held a fundraiser [for his legal defense].

We were protesting against that, we were trying to get people to come together and support the victim, but they didn’t even have the words to talk about sexual abuse. They didn’t know what it was, they didn’t know it was prevalent, there was no awareness that it was an issue, let alone a systemic issue. There was no groundswell of people who were aware of not just abuse existing but also the fact that rabbis don’t necessarily have the best interests of survivors at heart. So that’s changed a lot, and that’s because of a lot of the awareness raised by many activists both on the outside and the inside who have spoken about this openly.

The reason Walder is such a big deal is that he’s not just a beloved author, his books were speaking to something in the Haredi world that wasn’t spoken about. When I was growing up I was experiencing abuse, I was the product of divorce, I experienced the death of someone who was essentially a parent at a very young age, I had relatives going through life-long illness. All of these things were spoken about in Walder’s books — even sexual abuse. It means so much to so many people to have read Chaim Walder’s books because they didn’t feel seen by anyone else. You open up [U.S. Haredi publications] Mishpacha and Ami, and you don’t see this in there.

Because of that, this is the single biggest tragedy to occur in the international Orthodox community in my lifetime. Even more than the Meron tragedy [a crowd crush during a pilgrimage in northern Israel that killed 45 people] — which affected a lot of people who knew people who were killed or injured — it wasn’t a direct trauma, but now people are feeling a direct trauma. Because this book, this person that helped them so much, that connected with their soul in a way that the community wasn’t giving them, betrayed them in such a fundamental way. The trauma wasn’t experienced just by his victims, it was experienced by everybody who ever loved his books and found meaning in them, so that’s why you’re seeing a lot more of an explosive reaction.

In terms of what Pnina said about Aaron Rabinowitz having to convince Haaretz to take this case and the significance of it — it’s a problem I’ve run into in the U.S. as well. We used to have some Orthodox people in newsrooms in Jewish media in the U.S. That’s not true anymore, so the major outlets, for example the Forward, Jewish Telegraphic Agency, don’t have any Haredim or Orthodox people in the newsroom. So the reason it’s so difficult to get insight into this is because the newsrooms don’t have representatives of the community in them.

Much of the dialogue that’s been filtering out seems to be focusing on the social and power structures that have contributed to silencing survivors of sexual abuse. Can you talk more about those, and perhaps walk us through what some of those different structures are and the role they’ve played — communal media, for example, or schools, or other kinds of networks and institutions?

Pfeuffer: Like Asher was saying about Walder talking about things that weren’t spoken about in the community, what happened here is the rabbinical leadership recognized he was doing something important and they backed him. You can’t get your books out there, you can’t get your column in [Haredi newspaper] Yated [Ne’eman], and you can’t get a radio talk show, without rabbinical approval. The [rabbis] basically are in a place where they messed up, because they brought this person to the community and they endorsed him.

Another thing is that a lot of the conversation is about children. It’s a lot easier to talk about children in the Haredi community than about women — and most of [Walder’s] victims were women — because talking about women takes us into the area of talking about sexuality, which we don’t talk about. So it was very significant that there were children involved, because if there were only women involved I don’t know how far we could have taken this conversation. We still need to make a lot of inroads. On the other hand, what happened here with talking about nifga’ot v’nifga’im [female and male victims] has never happened in Israel in any community with such a case — male victims of sexual abuse are usually not brought up, and we brought that up.

[Walder] had detractors in the Haredi community because he was considered open-minded. The people burning his books now are the people who always wanted to burn his books. So it’s not as exciting as it looks. I’m also against book-burning, especially now that he’s dead. But I am happy with the public announcement of taking his books off the shelves. That’s a statement — it’s saying, ‘we recognize the pain of the victims.’

Lovy: One of the things I took issue with was the reactions from a lot of rabbonim saying ‘we can’t trust the press, they’re outsiders. Haaretz is anti-Haredi, it’s anti-religious, it’s anti-Zionist, these antisemites are trying to push us in all directions.’ And my answer to that has been, OK, if you don’t want them going to Haaretz then put it in Yated [Ne’eman]. But they’re not going to.

That ties into the institutional response. There’s denunciation [of sexual abuse], but what hasn’t happened in large part is an acknowledgement of the systemic problems that caused this. And [they are that] in our community, fundamentally, you are not allowed to report sexual abuse. You’re not. Agudath Israel has that as a stated policy, and every community I know of in the Haredi world, barring a select view, has as an unwritten policy that you have to ask a rav before reporting abuse, and then if you’re lucky you’ll get a heter [rabbinic permission] to go to the police, and if you’re even luckier they won’t call you a moser [a derogatory term for someone perceived as betraying a Jew to secular authorities] — because that also happens.

The one thing that’s absent here is a systemic response. And the reason you’re not seeing a systemic response is because acknowledging there’s a systemic problem would indict all the people who are the reason it exists. And they’re not willing to accept blame and relinquish any power.

Acknowledgement is great, but we need systemic change, and what that looks like is actual abuse prevention education in schools that is based on best practices. There needs to be an emphasis by leaders in the community that reporting to the police is actually what you’re supposed to do, with no caveats. There need to be resources on a communal level dedicated to survivors of sexual abuse. And there needs to be understanding that if someone reports sexual abuse it shouldn’t count against them for shidduch [match-making], it shouldn’t get them thrown out of school, their jobs, their housing. There shouldn’t be rabbonim writing public letters in support of molesters. There shouldn’t be fundraising for molesters! Let’s start there.

Pfeuffer: In Israel the police issue is less severe. There are more and more rabbonim who, at least officially, have the stance that you can go to the police. From my conversations with experts I don’t feel that’s the problem, the problem is people are afraid of someone who has so much power. And the communities are different — the American community and the Israeli community have a lot of similarities but there are some differences. In some ways the American community usually is more liberal, but not always, and I think on this issue we [in Israel] are in a better place overall.

Lovy: I just want to acknowledge that there is a very significant difference between the communities in Israel and the U.S., especially in regard to this. It does help [in terms of reporting abusers] that Israel is a Jewish country — it makes it very different in terms of interacting with the legal system and how rabbis see it. And as Pnina was saying, there’s a very big difference between the people on the bottom who are talking about and may acknowledge things that the leadership doesn’t, and the leadership itself. Those are two different things and they lead to two different systems of power. At the bottom you have a grassroots collection of power which can push back on the rabbonim who are issuing statements, but when it comes to actually doing something about it the power is still very much top-down. But the fervor is there at the bottom, and it’s been there for a while.

Let’s talk about some of the mobilization that’s been happening both in Israel and the United States. Pnina, I’ll start with you — what kind of activism is going on on the ground where you are? Who’s driving it? And is it building on existing work that survivors, and women more generally, have been doing in the community, or are there new initiatives springing up?

Pfeuffer: Lo Tishtok has been around for about five years — now it’s part of Magen [both organizations that advocate for abuse prevention and support for survivors] — and so all sorts of things are getting mobilized in that area. There is also protection education officially going on in the B’nei Brak municipality for the past couple of years. It’s become much more mainstream, and it’s easier in the Haredi community to address it in some way.

But there was a committee in the Knesset last week about how the police in Israel deal with sexual abuse in the Haredi community, and it was very clear that the police see the rabbinical leadership as their ally in this story. That means there are no women in the room, and Haredi women who have been abused by men in power are expected to go into a room with Haredi men and other men in power and speak about their experience being abused by the same types of people. To me, that’s a huge barrier to getting justice done, and it’s always a problem when you work with rabbinical leadership on these issues — there are no female [Haredi] rabbis so automatically you’re excluding women from the room. These are things that need to be addressed now before new structures get set in stone.

Lovy: There’s been limited change in the Haredi world, but the fact that the words ‘sexual abuse’ can be spoken aloud — that’s change. And that wouldn’t have happened without years and years of survivors, and people from the outside, pressuring people on the inside to do something.

With regard to abuse prevention education: [a response we get to Za’akah’s proposed curriculum] is that ‘we don’t want to encourage chutzpah in children,’ because one of the things in the curriculum — which was developed by a frum [Orthodox] woman — is that a child has the right to assert themselves, they have a right to assert their bodily autonomy, they can tell a parent, grandparent, uncle, rabbi, whatever, ‘no, I don’t want you pinching my cheeks, I don’t want you tickling me, I don’t want you touching me.’ We tell children they can be forceful.

What [Haredi leaders in the United States] have done is have a bunch of their therapists put out videos that don’t talk about body autonomy, or safe and unsafe touch, or personal boundaries, or asserting yourself, or reporting. It doesn’t talk about any of it but now it’s in yeshivas and they’re saying they’re doing abuse prevention education. That’s the real problem here — there’s a power base they’re clinging to, and any time they’re pushed into relinquishing a tiny bit of that power they take credit and pat themselves on the back, and they’re actually causing more harm than good in many cases. It’s very frustrating, because there’s no willingness to acknowledge the systemic nature of the problem and the responsibility of the systems of power to help correct it.

Pfeuffer: You said the word ‘chutzpah,’ and I think that’s a big thing, because being chutzpadik is something very bad. And a lot of kids internalize the abuse because it would be chutzpah for them to talk about an adult or an authority figure. It needs to be addressed because it’s very community-specific. I always say I raise my kids to be chutzpadik.

Lovy: That’s a really good point. It makes them uncomfortable. And saying to a child, ‘you wouldn’t want to be chutzpadik,’ is actually worse than saying nothing. If you say ‘chutzpah,’ a child is going to shut up.

What has been the impact of this story playing out so publicly? Do you think that it’s helping to apply meaningful pressure, or is the attention causing people to hunker down in a way that might obstruct change?

Pfeuffer: I only have anecdotal evidence, but I’ve seen mostly positive reactions. Yes, there are people who are extremely upset by this and pushing back, but overall people are a little relieved that this issue is finally being addressed. It’s a very uncomfortable issue for a lot of people — in every world, not just our world — and a lot of people are traumatized right now by proxy, or because they know someone who was abused, or they were abused themselves. Or they suddenly realized that something that’s been on the edge of their consciousness is actually abuse, or that someone in their circles is an abuser. That’s a horrible realization for people. It’s also too early to tell exactly where this is going, and we have to keep working to make sure it goes the right way and not the backlash way, because it’s totally possible that’s what’s going to happen. The fact that the leadership was very embarrassed by this story also has a part to play. They have to figure out how to play this, and right now they’re in a quandary.

Lovy: I would say it depends on what you mean by change. I haven’t seen anything systemic yet from the top, but getting back to the bottom people are engaging with and learning about the issue and confronting it in a way they never have. More people are wanting to come forward, are willing to engage with law enforcement, with the civil legal system, and with reporters in the wake of the Walder story. More people are now understanding what they’ve been through, and more families are understanding what their family members are going through.

I know from my own experience being abused as a child in [Brooklyn’s] Borough Park — you try talking to your family about it and they don’t get it. My uncles saw what was happening to me — they actually saw it — and one Shabbes [Shabbat] I spent hours with one of my uncles detailing what was going on, and he said he’d of course do something about it; two weeks later he was telling me I was making it up. So in situations like that, you’re now seeing conversations in families happening [where they recognize what a survivor] is talking about. It’s helping to start these conversations that I’m sure are going to lead to healing in families — and apologies, hopefully. As Pnina said, we’ve yet to see what the result of this is going to be for better or worse, so it’s incumbent on anybody who’s in a position to actually do something about this to keep pushing, because this is the moment where we can do something lasting.

I just want to say — we’ve been spending time talking about Haredim here, and I always want to temper that a little bit. There’s this feeling among other parts of Judaism and Orthodoxy of, ‘if we can pretend this is a Haredi problem then we don’t have to deal with it.’ And it is a Haredi problem, in many ways a uniquely Haredi problem; however, in the U.S. we have massive systemic problems and cover-ups in the Modern Orthodox world. I don’t want anyone to come away from this thinking, ‘our community is safe because the Haredim are the problem.’ There are lots of communities where this is a problem — on a macro level, on a micro level. Everybody has a responsibility here, and everybody has to look in the mirror here with this Walder case. Haredim have a lot to do, but so does everybody else, and that’s not to minimize the problems in that community — it’s to make sure that everybody feels the weight of this and the need to implement change in their communities and not ignore it.

You’re both members of these communities that are under an intense spotlight at the moment, and you also have your own histories, and experiences. What have the last few weeks been like for you personally?

Pfeuffer: I have the privilege and the pleasure to be supported by family and friends in whatever role I took in this, and that’s not always the case, so I’m very grateful and appreciative to them.

Lovy: Walder’s books meant a lot to me. Growing up, I was going through a lot, and I read every “Kids Speak” book and every “People Speak” book [by Walder]. So on the one hand, I’m not shocked anymore by anybody, but on the other, it was like, ‘Did it really have to be Chaim Walder? This person who meant so much?’

But the timeline on this case was crazy — a month from disclosure to him killing himself — so I barely had time to process it all, because I was busy helping people through this, and doing a lot of the culture war stuff that has to happen around this issue. So I didn’t really have time to stop and process. But then Shifra Horowitz was found dead, and that really got me. And even before I knew her name, I knew that this was a consequence of what had happened in the aftermath of Walder’s death. I know as an activist that suicide triggers suicide, and I knew that certain kinds of community response could increase the risk of suicide. And the statements that had been coming out since Walder’s suicide [in support of him] were going to kill somebody. So when I found out that somebody had died, my reaction was that it was bound to happen — but when I saw her name published, I couldn’t function. I was wrecked completely after that. But we pick up the pieces and keep going.