A trilogy of novels set in Palestine raises critical questions about the tension between identity and the desire to live.

By Salsabeel Hamdan

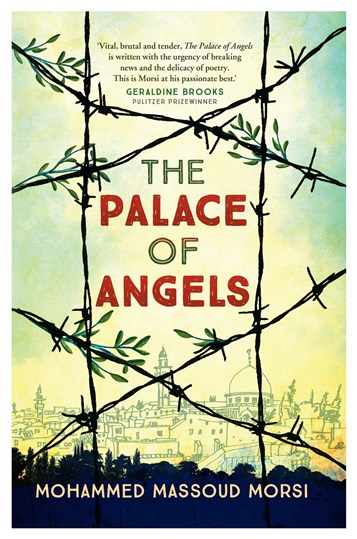

The Palace of Angels, Mohammed Massoud Morsi, Wild Dingo Press, 2019.

In The Palace of Angels, his trilogy of novels set in Palestine and the Palestinian diaspora, Australian-Egyptian novelist Mohammed Massoud Morsi places his characters in a time of radical change in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. With hope of a political solution fading, what happens to the people whose identities and life’s trajectories have been so deeply informed by a struggle for national liberation? Morsi asks this question in stories about individual Palestinians, which lead the reader to question the extent to which we fight ourselves and one another because we are locked in the past and cannot imagine a future.

Morsi wants his readers to glimpse a solution for the Palestinian question, while examining our own identity and the conflict itself. At the same time, Morsi makes it clear that we can only discover true freedom and belonging by facing our pain, and not passing it on to future generations.

The Palace of Angels tells human stories of gambling, suffering, intimate dreams and curiosity, in occasionally abstract form. Using simple language, Morsi shows that the conflict is more than political, religious, and cultural — that it is rooted in our sense of ourselves. He pushes his readers to examine the gap between the way we present ourselves to the world and our authentic inner selves.

As a Palestinian, I believe Morsi’s writing avoids bias, compelling both Palestinian and Israeli (and other) readers to question the identity they have acquired from years of conflict. This self-image traps both sides in a cycle of dehumanization and limits our ability to imagine a better future — let alone work toward one. His is a point of view one hears very rarely from either Palestinians or Israelis, all of whom are caught up in the grinding, destructive conflict for reasons they have stopped questioning.

Each of the novels in the trilogy presents a different perspective on living in a place of political violence that is seemingly without an end. What is Past is Dead examines self-conceptualization in conflict, and the tension between preserving one’s identity and the desire to live. Twenty-Two Years to Life juxtaposes love and war: what happens to our sense of self when we are drowning in hatred and hopelessness in the face of unimaginable loss. The Palace of Angels considers what is possible when we change the way we think, thereby transforming our actions and emotions. Yes, it is very difficult to change, but who do we want to be? How do we imagine our best selves?

What is Past is Dead takes place during the Second Intifada. It is narrated by a young man who was born in Denmark, the child of Egyptian immigrants, and his two Egyptian friends. The three young men set out to support the uprising against Israel, but their adventure takes a turn they had naively thought would never happen. Their quest is one for self-realization, from both the emotional rush of their own injustice and from that Israel imposes on the Palestinians. As Morsi puts it, “[the protagonist’s] journey is familiar, but not from his point of view.”

Twenty Two Years to Life is a love story narrated by Fathi, who falls in love with and marries Farida, but their marital happiness is undermined by infertility. They manage to travel to Canada looking for a medical solution to their problem, without success. The 2014 war in Gaza, which was sparked by the abduction and murder of three Jewish boys in the West Bank, becomes a third character in the novel. It places enormous pressure on the couple; here the novel takes the reader on a tragic journey of reality living in Gaza under siege. Morsi provides a gift to the people of Gaza, by humanizing their tragedy and breaking through the numbness of compassion fatigue. These are human beings with whom the reader can identify — not just weeping figures trapped in an endless, incomprehensible conflict.

Twenty Two Years to Life is a love story narrated by Fathi, who falls in love with and marries Farida, but their marital happiness is undermined by infertility. They manage to travel to Canada looking for a medical solution to their problem, without success. The 2014 war in Gaza, which was sparked by the abduction and murder of three Jewish boys in the West Bank, becomes a third character in the novel. It places enormous pressure on the couple; here the novel takes the reader on a tragic journey of reality living in Gaza under siege. Morsi provides a gift to the people of Gaza, by humanizing their tragedy and breaking through the numbness of compassion fatigue. These are human beings with whom the reader can identify — not just weeping figures trapped in an endless, incomprehensible conflict.

The love story in The Palace of Angels is complicated. Adnan, the narrator, describes a Palestinian worker who meets Linah, an Israeli soldier, at four in the morning at an infamous checkpoint. Linah, unlike the other soldiers there, behaves humanely toward a Palestinian woman unexpectedly giving birth at that Israeli checkpoint. Adnan and Linah become lovers; but as a consequence of her insubordination, Linah is transferred out of Jerusalem.

Ali, Adnan’s lifelong friend, falls in love with a Palestinian woman that he meets at a checkpoint. They become engaged, but soon his bride-to-be is raped and murdered before their wedding day. Emotionally unbalanced, Ali disappears and Adnan sets out to find him among the armed Palestinian resistance. Helped by his shady employer, Adnan reaches Gaza where he finds Ali, who makes it clear he’s committed to fighting and won’t return to the West Bank with Adnan. Ali enters a race against time and falling bombs to find his way from one prison to the other, and to his lost love — and to learn whether they are lovers or enemies.

Morsi focuses a deeply compassionate, humanizing lens on the inner lives of Palestinian people living under Israeli control. Narrated in the first person, his stories examine how the political conflict penetrates everyday Palestinian life, and consequently how it shapes a large part of who Palestinians and Israelis are — or who they think they are. From this strange place, Morsi leaves readers questioning their own sense of identity.

Salsabeel Hamdan, or Sal, is a young Palestinian freelance journalist who first started writing for We Are Not Numbers in Gaza, but today lives in Dubai. She has written for several other publications including Local Call, Washington Report, and worked with the award-winning journalist and filmmaker Jen Marlowe while she was in Gaza.