Much has been written about Israel’s so-called “mixed cities,” a term that, more than anything, reveals how anomalous they are in a country where separation is a foundational concept. But the story of the urban, Palestinian bourgeoisie, the group that Palestinian researcher Sherene Seikaly refers to as “Men of Capital,” in the years following the Nakba, has yet to be told.

The forgotten story of the Boutagy family, one of the few middle class Palestinian families that remained in the land after 1948, allows us to comprehend how this group thrived in the city of Hayfa during the British Mandate (I use the Arabic-to-English transliteration “Hayfa” to distinguish between pre-occupation “Hayfa” and “Haifa” after the city was occupied in 1948). This prosperity was made possible also by the ability of its members to maneuver between contradictions at a time rife with political, social, and economic changes.

The story of the Boutagy family following the Nakba, during which hundreds of thousands of Palestinians either fled or were expelled from their homeland and were forcibly prevented from returning, is the exception that proves the rule. The efforts the family made to remain, and the reasons it eventually left Haifa a few years later, illustrate the stark new reality in which the Palestinians found themselves inside the newly-established State of Israel.

The world of the Palestinians who remained in the city was delineated, on one side, by new external borders and a disconnect from the Arab world; and on the other, by internal borders that separated Palestinians between cities and villages, as well as between Palestinians and Jewish Israelis living in the cities themselves

Meanwhile, the bourgeois Palestinians faced a new political reality whereby the Israeli state insisted on a Jewish monopoly over capital and sovereignty, and also disconnected, using those same new borders, any connection between Palestinians and the world. In this reality, members of the Palestinian middle class who tried to maneuver between capitalist aspirations, modernity, cosmopolitanism, and nationalism did not find a place in the new state.

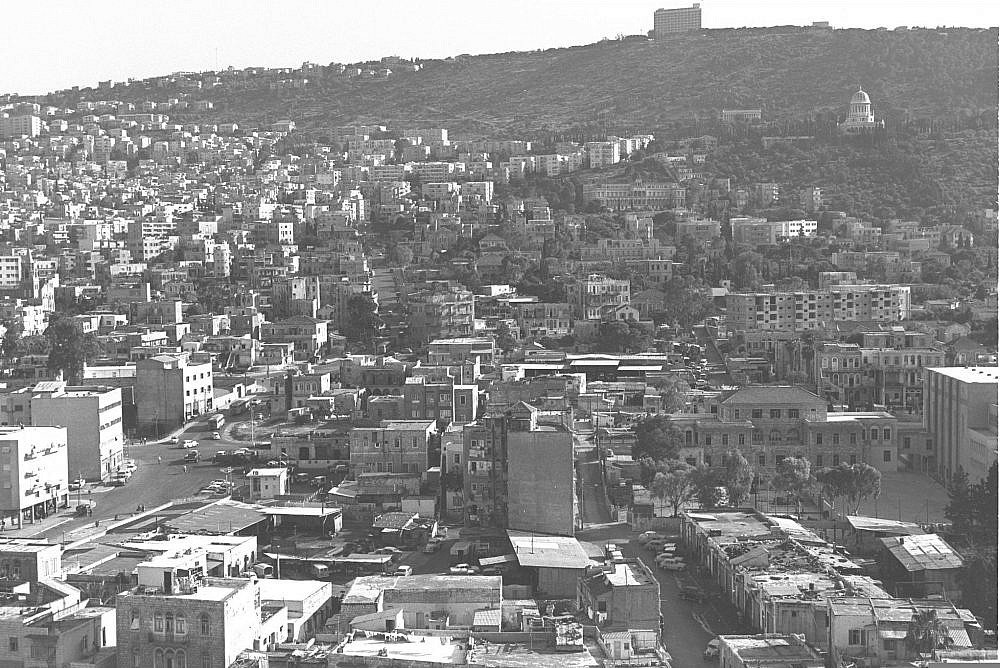

Hayfa-Haifa constitutes a unique example in the study of cities during the early state-building years, particularly for the status of Palestinians who became citizens of Israel, whom I will call here al-mutabaqqun (those who remain). As opposed to the “seized territories” — referring to the land that was conquered by Israeli forces in 1948 after it was designated to be part of a Palestinian Arab state, in accordance with the 1947 UN Partition Plan — Hayfa was designated by that same plan to be part of the Jewish state.

In principle, and according to commitments made by the Zionist leadership in relation to the Partition Plan, Palestinians in the city were supposed to enjoy equal rights in the future Jewish state. But an examination of Israeli spatial policy in the city, alongside the population management policy that targeted the Palestinians who remained, is indicative, perhaps more than anywhere else, how the Jewish state imagined and shaped the cities from which Palestinians had been expelled, and concurrently, how it imagined and shaped the status of Palestinians within the Jewish state and within the city.

The nineteenth century was one of lightning-fast growth and prosperity across the Ottoman Empire. This time also saw major economic, social, and cultural changes as a result of the Tanzimat, a series of Ottoman reforms and reorganization.” It was a time of renewal and administrative reform, alongside growing industrialization.

Hayfa benefited greatly from these changes. The city’s location along the coast, the expansion of its port, and the gradual growth of its trade with Europe — alongside the construction of the Hijazi Railroad in 1905 — turned Hayfa into a center of maritime and continental commerce. This development encouraged merchant families and capitalists from other cities in Palestine, Syria, and Lebanon to move to the city. The Boutagys, which originally came from Acre (Akka), was one of those families.

Theophile Seraphim Boutagy, who would go on to establish the family business T.S. Boutagy & Sons, was born in Hayfa in 1870. Already from the middle of the 1920s — and thanks, among other things, to the family’s British citizenship — the Boutagy’s business specialized in importing goods from Europe. These goods fit the tastes of the locals as well as the Europeans in the city, including European Jews who settled in it. The business continued to expand, opening branches in Jaffa and Jerusalem. The family acquired property, including a beach, the Windsor Hotel in Hayfa, and Jerusalem Hotel in Jaffa.

During the first half of the 20th century, the freedom of movement and the open borders in Bilad al-Sham (the Levant) — which includes present-day Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Israel-Palestine — was a significant factor in the economic, social, and cultural prosperity in Palestine’s cities. This freedom of movement also helped strengthen Arab-Palestinian identity and emboldened Palestinian national aspirations.

The blossoming of Hayfa al-Jadida (“The New Haifa,” which was actually designated “The Old City” by the British Mandate authorities) — including its neighborhoods, public squares, cafes, and markets, alongside the strengthening of the Arabic-language press, played a central role in this process. The growing opposition to British colonialism and Zionist settlement also strengthened Palestinian national aspirations — a process that led to the height of national and political unrest in 1936, with the outbreak of the Arab Revolt.

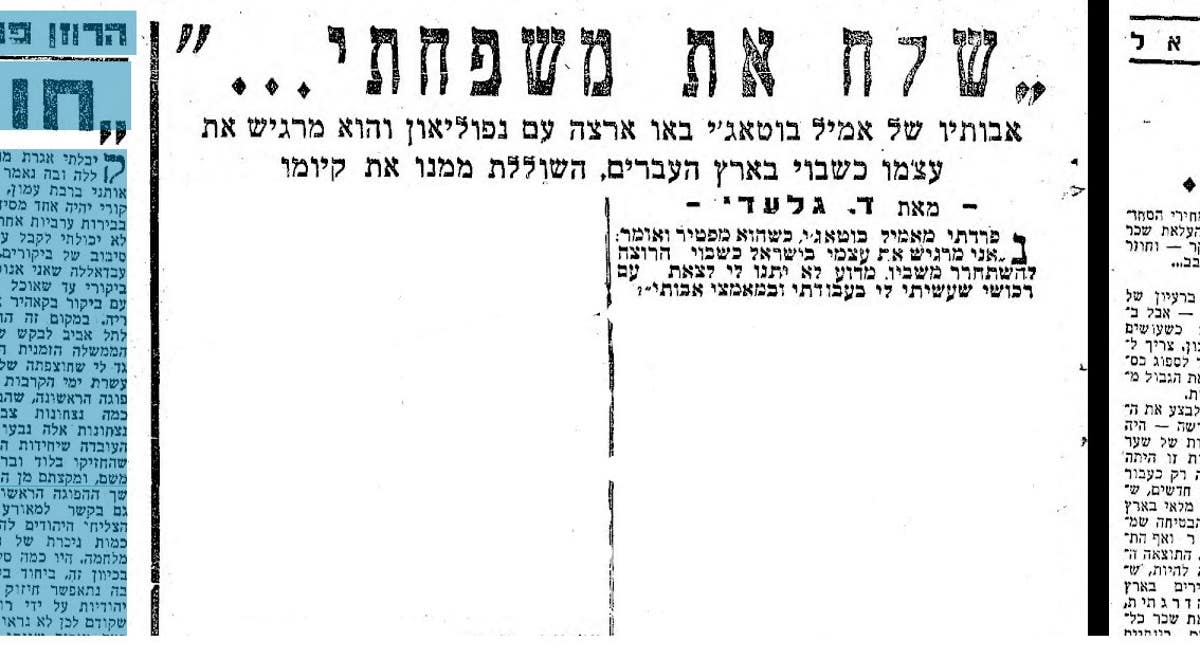

As opposed to Charlie Boutagy, who was a British informer during World War I, far less is known about the political positions of Emile Bougaty, Theophile’s other son who succeeded his father in running the family business. For instance, Emile Bougaty’s stance vis-a-vis the Arab Revolt was, on the face of it, full of contradictions. The Hebrew-language Do’ar Hayom reported in April 1936 on Emile’s vigorous opposition to the six-month general strike that had been declared by the Palestinian leadership.

Two years later, in July 1938, the Hebrew Davar newspaper reported about a flyer, signed by Emile, that called for donations for the “Arab heroes” of the revolt. Emile himself donated 50 pounds to the rebels. One can assume both reports were accurate, and that he wanted to maintain the ability to move with ease between his capitalistic aspirations and his good relations with the British on the one hand, and the growing Palestinian national aspirations on the other, at a time of conflict and risks.

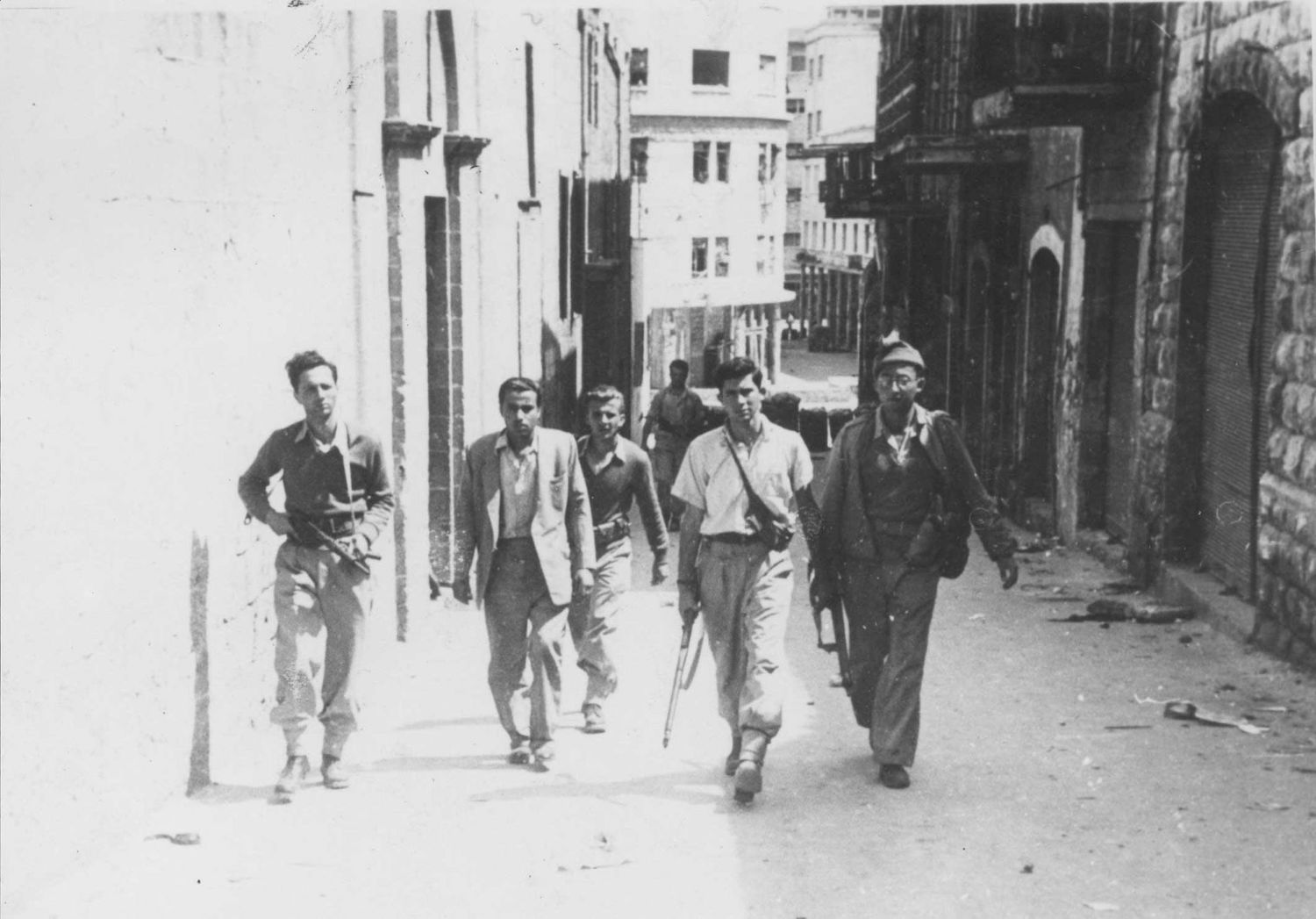

The British Mandate authorities left Hayfa in June 1948. From that moment, the spatial, economic, and social reality in the city changed drastically, particularly during “Operation Shikmona” — an Israeli military operation launched to demolish Hayfa’s Old City following the war. Contrary to popular belief in both the academic literature and the accepted narrative, the operation was initiated by local officials from the city’s “Emergency Committee,” an institution that included the top institutions of Ha-Yishuv Ha-Ivri (The Jewish settlement in Palestine) in the city. With the end of British rule, the committee declared itself the supreme civilian body in the city. Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion supported the operation wholeheartedly.

Despite opposition and protest by Palestinians, it was reported that in December 1948, the great majority of the 3,200 Palestinians who remained in Haifa had already been moved to the “ghetto” in the neighborhood of Wadi al-Nisnas, where their freedom of movement was restricted.

Like many other Palestinian residents of Haifa, the Boutagy family tried as hard as they could to maintain at least part of their previous lives. For example, on June 30, 1948, as the British prepared to leave the city, Emile Boutagy sent a letter addressed to the Haifa police in the name of T.S. Boutagy & Sons, in which he wrote:

As you are aware the Army cordoned our premises at No 30 Jaffa Road and prevented us from conducting our normal trade. With evacuation, we have every hope that conditions will revert to normal and that you will now open the road to the public and allow us to resume our normal business relation with the public.

That same day, Boutagy sent a similar letter to Moshe Shertok (Sharett), the Foreign Affairs Minister, regarding his family store in Jaffa:

I am anxious to visit my branch in Jaffa facing the CID headquarters and all endeavors and applications made so far for a pass have been fruitless. One Dignitary tossed me to the other with the result that I am still in mid air unable to undertake this visit […]. I most respectfully venture to approach you for your kind help in the matter.

Would it be possible for you to let me have a letter of recommendation or some certificate to enable me to visit Tel-Aviv and from thence endeavor to have a glimpse of my branch in Jaffa to salvage whatever is possible?

Two weeks later, Boutagy sent another letter to Atty. Yaakov Salomon, the liaison officer with the British:

I attempted to visit my farm at Tal Emile today and was stopped at the block road at the end of the asphalted road Ahuza and was asked to obtain a permit from you. I respectfully apply for a permit to enable me to visit my farm three times weekly. As you are aware I have a little farm at Tal Emile and also my quarries are between Isifia and Daliat al Carmel.

In an attempt to remove the restrictions imposed on his business and prevent the transfer of his family to the ghetto, Boutagy once again tried to use his ability to maneuver between conflicts. Carefully and under a cloak of secrecy, he tried to elicit members of the new regime to meet his demands, while implying that in return he would be willing to collaborate with them.

Unlike other letters, he marked a letter he sent in June 1948 to Harry Beilin, a representative of the Jewish Agency’s liaison officer to the British army in Haifa, as personal and confidential. In the letter, he detailed demands relating mainly to his business operations, as well as requests to protect his family and employees. He also wrote in the letter that “in order to encourage non-Jewish elements to collaborate with you it is essential to have concrete evidence of your goodwill and good intentions before one can take the plunge and offer his collaboration in the political domain.”

In July, Boutagy sent an additional confidential letter, this time to Minister of Labor and Construction Mordechai Bentov, which included a request not to move him and his family to the ghetto. In the letter, Boutagy expresses his loyalty to the “valiant and Noble race” to which Bentov belongs, and noted that “In fact I have lived almost all my life amongst you so that I feel an integral part of you and in the present calamity I should like to do my humble bit to be helpful and useful in every possible way.” Boutagy also emphasized his Christian background, and encouraged Bentov to win the friendship of the “CHRISTIANS,” both Arab and non-Arab. Boutagy also recommended Bentov contact “the great BITHOP MUBARAK OF BEIRUT who is a very strong supporter of the JEWISH STATE,” and offered his help in doing so.

Order No. 12 issued by the Hayfa headquarters of the Haganah [the most prominent Zionist pre-state paramilitary group], which was published in April 1948, determined the areas in which Palestinian Arabs were allowed to live in the city. Al-mutabaqqun, including Boutagy, knew that the order to transfer people to the ghetto was given only to Arabs.

In an attempt to increase the chances that his request to avoid that fate would be granted, Boutagy did not content himself solely with declaring his allegiance to the Jewish state as a Christian, but also denied that he was even an Arab. “[…] First of all I am not an Arab as my family hails from MALTA and have been living in ISRAEL for a considerable number of years. Secondly, we have never lived in Arab quarters in all our lives as we have all along lived in Jewish Suburbs […],” he noted in his letter to Bentov.

The documents in our possession do not provide an indication as to whether Boutagy’s request was granted. However, we do know that he claims that the import license granted to him after 1948 was limited, and that the terms of the license were much more restricted than the terms of those granted to other Israeli-Jewish merchants at the time. This reality led Boutagy to send another letter to the Minority Affairs Minister Bechor-Shalom Sheetrit on April 1, 1949, about a year after the Nakba, in which he asked for help leaving the country. This request was seen by Sheetrit as a “pure personal affair,” one that did not concern his office.

It is evident that the reality did not improve for the Boutagy family in the following years. In 1952, Emile Boutagy published an ad in the British press, including the Jewish Chronicle, the British Jewish community’s most prominent newspaper, seeking to sell his property. In an interview with the Israeli Maariv newspaper in April 1952, Emile noted that he had been robbed of his import licenses, that the beach under his ownership had been taken from him, and that his requests to bring back his skilled workers from Lebanon had been rejected. He summed up the interview as follows: “I feel imprisoned in Israel.” Sometime after the interview with Maariv, Emile left the country, apparently for Lebanon. A few years later, the family settled in Australia.

For al-mutabaqqun, those who remained, the creation of Haifa marked the outset of the devastation of Hayfa: the city’s urban cosmopolitanism was decimated by cutting Palestinians off from the Levant, eliminating the channels for prosperity and economic and cultural networks. Israel’s spatial policies isolated the urban mutabaqqun from the world, including the Arab region, as well as from surrounding Palestinian villages and even from the city itself. Israel’s population management was characterized by the separation of Arabs and Jews, and the persecution and persistent rejection of Palestinian national identity — along with blocking the access of non-Jews to exclusively-Jewish sovereignty.

The flexibility and ability of the Palestinian urban bourgeoisie to maneuver between different elements of identity, both national and religious, and the multiplicity of channels that connected them with the world — which, among other things, helped to bolster their prosperity — had now been replaced by a rigid Jewish ethnicity, a Jewish monopoly on capital, and the blocking of al-mutabaqqun from their surroundings. In this reality, there remained no place in Haifa for these “men of capital.”

The Boutagy family therefore had no place in Haifa, and its story had no place in Palestinian or Zionist historiography. Their story presents the absurdity and complexity of the life of al-mutabaqqun immediately following the Nakba, and also challenges the binary of heroism and weakness, of complicity and resistance.

At the same time, it is a story that exposes the deception of “coexistence” in Israel’s “mixed cities,” as well as the falsehood that Israel has brought democracy, progress, and economic prosperity to the Palestinians that remained. With that, it further challenges the binary narrative that identifies Israeliness with “modernity” and “the West,” as opposed to Palestinian, Arab, and Mizrahi identities that are so often identified as “anti-modern.”

A version of this article was originally published on the Social History Workshop’s blog, published on Haaretz’s Hebrew site.