“Prisoners of the Occupation” was performed this week in Tel Aviv, a fact that Einat Weitzman, the actress who wrote and produced it, regards as a triumph for art. In May 2017, when it was still in the development stage, the mayor of Acre forced the steering committee of the prestigious Acre Festival to reject the play for political reasons. The decision caused an uproar: Avi Gibson Bar-El, the artistic director of the festival, resigned — as did members of the steering committee. Several of the participating artists also withdrew from the festival in protest.

The reputation of the festival was badly damaged by the incident, and Weitzman did not believe the play would be staged for an Israeli audience in the current political climate. Yet this week it was performed at the Tmuna Festival, despite the protests of Culture Minister Miri Regev.

Weitzman funded the production with an online donor campaign, and with prize money she received in Norway.

Perhaps because public attention is focused on the political drama over the failure of both Likud and Blue & White to form a governing coalition, or on the criminal indictment of Netanyahu, or because they are simply weary of the subject, the staging of the play caused almost no controversy — except for a few small items on news sites, and Miri Regev’s recycled, rote condemnation.

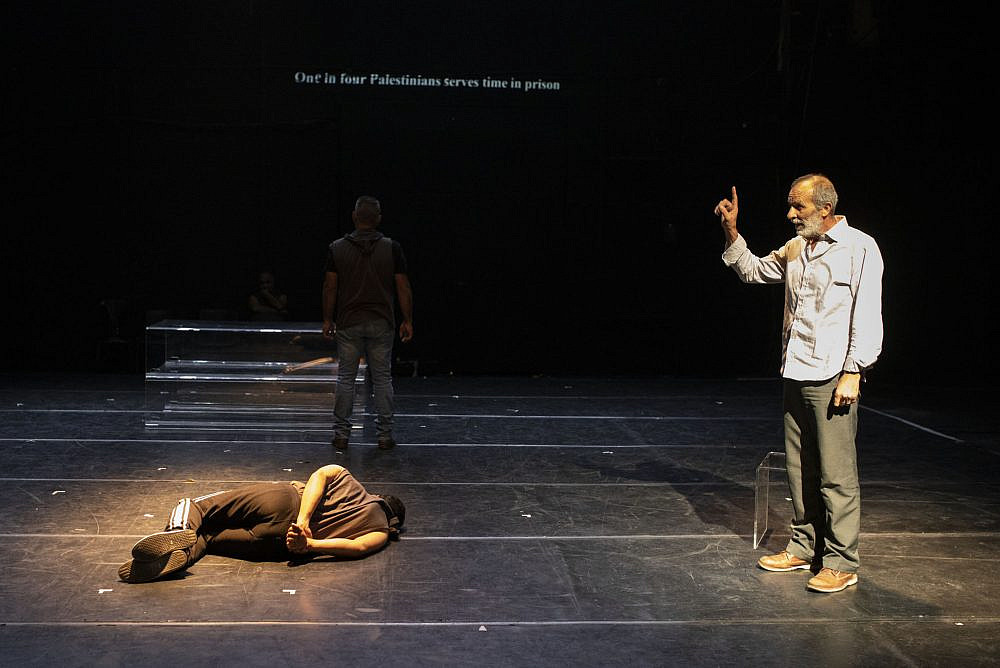

The play, which is mostly in Arabic with Hebrew supertitles, is performed by four Palestinian actors — Kamal Basha, Jalal Masrwa, Rabia Khoury, and Byan Anteer — and by Weitzman. The plot revolves around several scenes of daily life in prison, with the actors reenacting incidents like interrogations, hunger strikes, family visits, and solitary confinement cells.

The stage is almost bare, except for transparent plastic blocks that are used interchangeably as an interrogation table, a dungeon and a bed. The stories the actors narrate are almost unknown to the Jewish-Israeli public. No one could walk away from that production still believing that an Israeli prison offers Palestinian political prisoners conditions similar to a hotel vacation.

Weitzman wrote the play after she met a Palestinian citizen of Israel who had been released from prison after serving 30 years. She sat with him every week for a year, listening as he recounted his experiences of prison life. While working on the play, Weitzman met with additional former prisoners who were from East Jerusalem and the West Bank. She describes the play as “re-enactments of memories that are put on the stage, in order to give life to the things people told me.”

Prisoners of the Occupation is documentary theater, in which Weitzman plays herself. While most of the play is in Arabic, Weitzman acts as an interpreter for the audience. “It relaxes the audience and helps break through their resistance,” she explained. “Theatre allows us to talk about things that are impossible to discuss under most circumstances.”

Weitzman met with Dareen Tatour, the Palestinian citizen of Israel who was sentenced to two years in jail for publishing a poem on her Facebook wall, which the security services claimed was a call to political violence. “I had to speak with a woman in order to understand this through the female experience, and only then go back to the men who served time in jail,” she said.

The play opens with Weitzman delivering a short monologue, in which she recounts the cancellation of the play at the Acre Festival and answers preemptively some of the questions the audience is likely to raise. The first question is whether the prisoners on whose stories the play is based were convicted of participating in armed struggle. “The people whose stories are told in this play have already served their time or they are still in prison. Some were sentenced at trial and others were not granted a trial. Some of them are in prison for violent resistance, and some because they published a status on Facebook.” Weitzman concludes her opening monologue with a declaration: “I am not here to judge these prisoners. This is not a courtroom; this is a theater.” And then the first scene begins — in the interrogation room.

The role of narrator is played by Prisoner X, who has already been released from prison and is recounting his experiences. “Although he has been released from prison, mentally he is still there — the prison is inside him; he is stuck in the dungeon,” says Weitzman. Jalal Masrwa (Fauda, Sandstorm) plays the role of Prisoner X as a young man, standing in the middle of the various reenacted scenes from his life in prison.

Masrwa said he originally had reservations about performing in a politically controversial play. Reading the text, however, changed his mind. “I couldn’t stop reading, it was very powerful and moving. I felt connected to the story.”

Masrwa understands that Israelis are uncomfortable listening to stories about Palestinian political prisoners. He stresses that no one involved in the play is trying to stir up anger, or create an atmosphere of incitement. He is against violence, he says, and so is everyone involved in the play. “But a person who has been oppressed for his entire life has a different worldview. We are using art as a means of inspiring people to think about this.”

One of the central scenes in the play was written by Walid Daka, a Palestinian citizen of Israel who has been a political prisoner since 1986, when he was convicted of involvement in a plot to kidnap and murder an Israeli soldier. When the Maidan Theatre in Haifa staged Parallel Time, a play about Dakar’s life, the resulting storm of outrage led to the cancelling of the theatre’s municipal budget. In the scene, which Dakar wrote after he was transferred to a different prison as punishment for having smuggled cell phones, he walks in the yard, sees his shadow, and imagines that it morphs into the little boy he once was. Weitzman said, “He sent it to me as a story, and I worked it into the scene.”