Due to the influx of gay tourists who arrived in Tel Aviv for Pride Week, we can say with some certainty that more Belgians and Danes marched in the Gay Pride Parade than Palestinian citizens of Israel. That’s not just because of the understandable need for the gay Arab population to maintain a low profile. Gay Palestinian organizations boycott pride events because they consider them examples of “pinkwashing” – presenting Israel as enlightened due to its treatment of homosexuals, while denying the human rights of others.

Al Qaws (The Rainbow), familiar to the gay community in Israel mainly because of the queer Palestinian parties it holds in Tel Aviv, was among the organizations that did not encourage its members to march in the parade. But Al Qaws did not ignore Pride Week – it provided an alternative. On the Thursday prior to the parade, Al Qaws members met at Cafe Dina in Jaffa, with people from the Qadita website, for an event called “Reading Queer Texts in Arabic.”

Qadita is a site founded by Alaa Khlakhal and is dedicated to culture and criticism in Arabic. It offers its readers a rare and permanent column of often artistically ambitious queer writing, edited by Raji Bathish. “The Israeli LGBT culture is fully interwoven with Israeli militarist culture,” says Bathish. “It tries to emulate the Israeli mainstream, in the central Tel Avivian, hetero-normative sense, with its army and gyms. The queer movement needs to change the system and social structure from the base, rather than reaffirm them, and the LGBT movement here only deepens the system of oppression.”

The name of Bathish’s column, hosting diverse works of literature and commentary, was recently changed from “Gays and Texts” to “The Queer Text Corner,” in an attempt to separate it from the Arabic-language gay blog culture prevalent in the Middle East, to stress queerness as a principle, and to create a clear reference to literature. The event celebrating it, attended by about 40 men and women, was a break from the mainstream pride events not only in its use of the Arabic language, but also in its focus on challenging content.

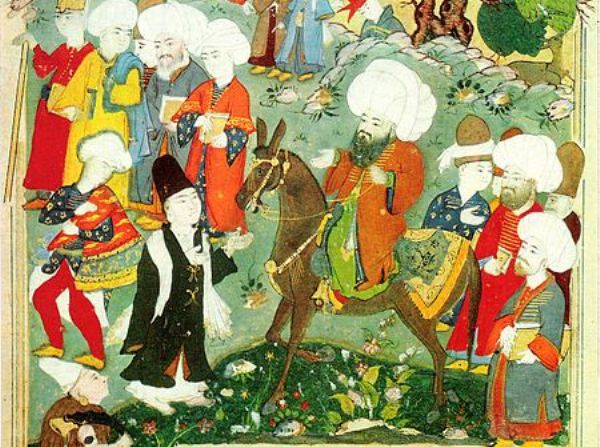

Activist, cultural figure, and DJ Muhammad Jabali spoke about queer traditions in Arab literature, including homoerotic poetry from the Middle Ages, and openly gay artists who resided in the courts of the caliphs. Sociologist Dr. Ismail Na’ashaf and Islamic art researcher Dr. Hosmi Shahadi also participated. The theories of Edward Said and Mary Douglas were shared, and the ghosts of Mahmoud Darwish’s Tel Avivian poems were read. Although no desire for men is expressed in the poems, their liberalism excludes them from collections of his poems published in Arabic.

The artistic program was of particular interest, showcasing performance artists reading texts from queer literature. Facing a mirror, artist Tony Haddad read a passage describing a shave the morning after a night of love-making. The person shaving remembers the act of love and the man with whom he shared his bed. He ponders the beard and removing the beard. After the reading, the audience realized that Haddad had been bound to the cafe door. Another text included the line, “Every time I put on lipstick, my prick gets hard.”

In light of this creative and intellectual endeavor, the gay Hebrew beach party seems particularly flighty. In previous years, more radical and political elements tried to break out and march in an alternative parade. This year a number of activists organized a march within the mainstream parade, wearing black and carrying signs with slogans ranging from “There is no pride in the occupation” to “Pride without racism.”

The group’s Facebook page featured a debate on the proximity of the Pride events to the attacks on refugees in south Tel Aviv. Activist Elizabeth Tsurkov shared an article on the page describing Tel Aviv Mayor Ron Huldai’s complicity in a poster campaign advocating the removal of refugees from the city. “Tel Aviv cannot be presented as a liberal city while pogroms are taking place and the municipality allots funds for a campaign calling on Israel to deport and jail refugees,” Tsurkov wrote.

Jabali’s words emanate in Tsurkov’s claim, when he explains why the Pride Parade is unacceptable from the Palestinian perspective. “This parade is taking place during the same week marking the 45th anniversary of the occupation. How can you participate in the parade that your boyfriend from Ramallah can’t reach?” Is Israel too dark and difficult a place for pride celebrations? Maybe, maybe not. In any case, the parade estranges many, who experience discrimination on grounds other than sexual orientation, as well as those aware of the discrimination that others face, who feel forced to look for creative solutions.