Between 1949-1967 there was a radio station that united West Bank Palestinians and Jerusalem Jews. It wasn’t interested in propaganda or demagogy, only playing the most popular Western and Arabic music. A brief history of Radio Ramallah and the legacy it leaves behind.

By Niros*

Last Saturday night, while walking on Tel Aviv’s Ha’aliya Street, a man from Ramallah turned toward me and my partner. He and three of his friends were a little drunk and in a good mood. It seemed that they had just returned from some Tel Aviv club. He spoke to us first in Arabic before switching to broken Hebrew and asked how they get to Jaffa Gate, before immediately correcting himself and asked how to get to the Tel Aviv central bus station. We gave him directions and he walked off with his friends.

Al-Qaws (“The Rainbow”) is the umbrella organization for the Palestinian LGBTQ community. Its office is located in the Jerusalem Open House, but its parties – which are attended mostly by LGBTQ Palestinians from both sides of the wall, as well as queer Jewish Israelis who dig the scene – are held in different Tel Aviv clubs. The DJ spins both pop and Arabic music, drag shows and belly dancing take place, people enjoy circle dancing and grinding, men walk around without shirts while women wear hijabs – the atmosphere is somewhere between a hafla (Arabic for “party”) and a gay Tel Aviv party. From what I remember, the organizers claim that gays from the West Bank cannot hold their parties there out of fear of harassment, and that Jerusalem, I assume, is just boring. This is how Tel Aviv became the center of the queer Palestinian parties.

I have never visited Ramallah, but I have read several interviews with Ramallah residents who talk about the queer scene in the Palestinian cultural capital, and claim that it is only ostensibly underground – bars, clubs, meeting points, etc. Different heterosexual interviewees stated that Ramallah needed its own pride parade in order to bring tourism and promote business. Jerusalemites, on the other hand, consistently describe their city as lacking culture or nightlife. If a Jewish Jerusalemite is interested in night life, he or she goes to the coast. If a Jerusalem Palestinian is interested in night life or culture – cinema, theater, shows, parties – he or she goes to Ramallah.

My grandmother and her sister were born to an old Hebronite family, but after the 1929 riots moved with their families to the Nahlaot neighborhood in Jerusalem, where they spent their childhood and teenage years. My grandmother’s sister, may she rest in peace, who was older than my grandmother by 10 years, told me that during the 30s, she would go out with her friends to Ramallah. She had to sneak out of the house; otherwise her father would whip her with his belt. But she took the chance in order to go out and gain some exposure to the West: Ramallah had dance parties with swing music, there was alcohol, smoking, men, and flirting with British soldiers. Jerusalem had none of these things.

The Voice of Israel and Radio Ramallah

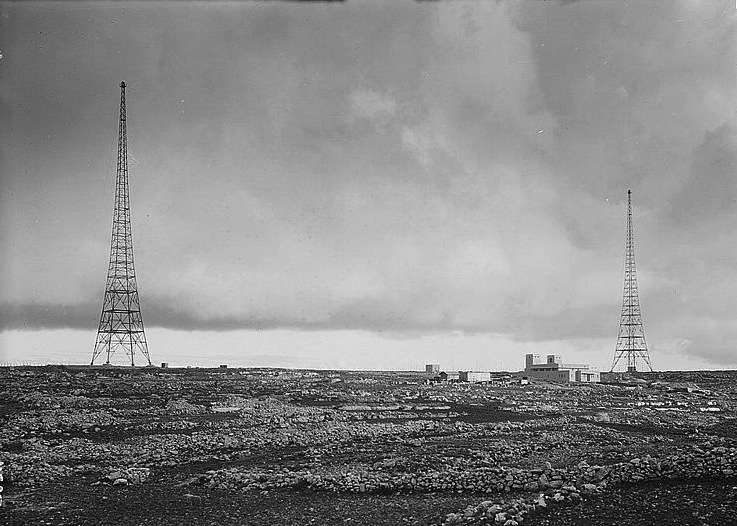

Regular radio broadcasts began in England in 1922. In 1924, the mandate government in Palestine was given its first license for radio receivers. Most of the receivers belonged to Jews until the end of the 30s, and the majority of people listened to BBC broadcasts. The Palestine Broadcast Service (PBS), which began operating in 1936, was headquartered in Ramallah due to technical and topographic considerations. The broadcasts were mostly in Hebrew, some in English, and even fewer in Arabic. The State of Israel inherited the channel under a new name, “Kol Israel” (The Voice of Israel), and moved its headquarters to Jerusalem. The Kol Israel broadcasts in Arabic, which were given their own station in 1958, consisted of propaganda that was intended to deter the enemy, and convince Palestinian citizens to accept authority of the Jewish state, and to internalize that they would do well to develop the country and let it succeed.

The absurd part is two-fold: on the one hand, Jews in Arab countries would clandestinely listen to the Arabic propaganda of the Zionist entity. They listened to its broadcasts because they wanted to be updated, and listened specifically to the Arabic programs because Arabic was their mother tongue and they didn’t understand modern, invented Jerusalem Hebrew. They listened secretly, since there was a fear of being targeted for listening to Israeli broadcasts where they lived. I do not know the number of listeners among non-Jewish Arabs, although it is quite amusing that the propaganda made its way to Zionist Jews in the diaspora. Professor Sasson Somekh describes his disappointment and feeling insulted after discovering that the same Daoud al-Natur, whom he listened to with his family in Iraq (before their immigration to Israel), the same old Palestinian who openly lambasted the Arab leadership and praised the Jewish state on the Zionist radio, was actually a young, Jewish Baghdad-born Jerusalemite.

On the other hand, many immigrants from Arab countries – as well as many young people in Israel – preferred the Arabic Radio Ramallah. Kol Israel’s Arabic programming did not interest them, while it’s Hebrew programming was boring and depressing. These programs had a very Jerusalem vibe. Heavy. Boring. It gave too much of a voice to Hebrew professors, educators, biblical verses, politicos and politicians.

Moreover, the radio was one of the most important tools in Israel’s “melting pot” enterprise. In 1948, one in every four Israelis had a radio – a higher percentage than in most industrialized countries at the time – and Kol Israel was the only Israeli radio station. Until the establishment of the Broadcasting Authority in 1965, Israeli radio was under the direct command of the Prime Minister’s Office, or in other words, under the direct supervision and management of David Ben-Gurion. Thus, Kol Israel openly took it upon itself to educate new immigrants, and especially those who arrived from “the East,” in order to mold their aesthetic, cultural and political tastes. The station openly declared that its goal was to provide values of high culture such as classical music, Russian poetry theater and Anglo-Saxon radio plays to a public that was “lacking the most basic and fundamental principles of civilization.”

A 1950 listeners survey among Israeli soldiers shows that approximately 15 percent of them listened to Radio Ramallah. When Kol Israel’s Arabic station was opened in 1958, almost 30 percent of Israelis listened to Radio Ramallah. Reshet Bet was established in 1960 under the name “HaGal HaKal” (The Easy Wave) as a response to the neighboring cultural threat. The threat was educational rather than strategic, as Radio Ramallah never did propaganda. It was simply fun. It played modern Arabic and Western music, and it included lighthearted skits. HaGal HaKal did not succeed in its attempts to offer entertainment that wouldn’t corrupt the youth. When they’re transmitted from Jerusalem, even entertaining broadcasts sound too educational.

As a proud Jerusalemite who often rides in Jerusalem taxis, I can say that even today, most of the city’s Israeli and Palestinian taxi drivers alike prefer Radio Jerusalem and Ramallah Radio. Radio Jerusalem provides a forum for Mizrahi voices and Mizrahi music more than any nationwide station. And Radio Ramallah is still a fun station that plays a wide variety of music from the West and the Levant. Many drivers, and perhaps many Jerusalemites, understand both languages, or they at least equally enjoy the broadcasts and music in both languages.

Yehuda Poliker – Radio Ramallah:

Traditional and non-traditional bridges

Much has been written about the way in which Jews from Arab countries could serve as a bridge between the Jewish state and Arab Middle East, and the way in which the Eurocentric Zionist hegemony made strides to put an end to this opportunity. But when I think about Radio Ramallah as opposed to Jerusalem’s radio, about the Western swing parties in the 1930s or the queer Palestinian parties in Tel Aviv during the 00s, I think about modern Western culture and its potential to form a bridge. Postmodernism and the anti-tradition common to rebellious teenagers create an opportunity to let go of traditional ideologies and identities for the sake of life itself. For the good of the here and now. Another missed opportunity lies in the similarity between Tel Aviv and Ramallah – the way their culture and nightlife pull Jerusalemites away from their hometown – which comes at the expense of the similarity between the Arabs of East Jerusalem and the Mizrahi Jews of West Jerusalem.

I predict that when Ramallah has its own pride parade, it will be more similar to the Tel Aviv march. I predict that it will be reminiscent of the swing parties of the 1930s or the Al-Qaws parties in Tel Aviv. Even if a bridge between West and East Jerusalem is found – based on similarities between the two or the recognition of the history and traditional significance that it has for both Jews and Palestinians – it will always remain boring and pedagogical. The cultural capitals, where nightlife and the LGBT communities thrive, will always remain in Ramallah and Tel Aviv. Either way, when Ramallah hosts a parade, I hope to take part in it, and maybe afterwards ask a local couple, in broken Arabic, how to get to the central bus station.

* “Niros” is the nome de guerre of a tour guide from Jerusalem. He maintains the Hebrew-language blog “K’tamim.”