Boxes stuffed with clothing, a few backpacks, and a portable tent: these were what remained of Marah Mahdi’s possessions as she sheltered at a UN facility in Gaza’s southern city of Rafah in early May. A 23-year-old Palestinian journalist from Gaza City, Mahdi had survived a winding, tumultuous journey that was emblematic of the endless displacements suffered by most of the Strip’s population — and one that is still far from over.

Mahdi was at home on Oct. 20 when Israeli airstrikes and artillery bombs shelled her neighborhood in preparation for the army’s ground offensive. The next morning, she and 11 members of her immediate and extended family packed what they could and headed south, fleeing with only the clothes on their backs, some essential documentation, and food.

After their initial escape, the Mahdis found temporary shelter in a school in Nuseirat, which soon became unsafe due to continuous Israeli airstrikes. Forced to move again, they made their way to Deir al-Balah, hoping for a semblance of safety. Each move brought new challenges, from finding food and clean water to avoiding the constant threat of shelling.

Yet their arrival in Rafah in early November did not signal the end of their troubles. For the past seven months, Rafah has served as a refuge for over 1.4 million Palestinians fleeing from the north of the Strip by the orders of the Israeli military. The city, overwhelmed by the influx of refugees, was barely able to provide the essentials. The Mahdi family first took shelter in a UN elementary school in the eastern part of the city, but were forced to relocate within Rafah multiple times as humanitarian aid dwindled.

Then came Israel’s invasion of Rafah four weeks ago, which has pushed hundreds of thousands of Palestinians to flee once again. This time, however, there is a pervasive uncertainty as to where they should go.

“We are witnessing a devastating situation across Gaza,” Mahdi told +972. “From Jabalia in the north to Khan Younis and Rafah in the south, we have no safe havens. Staying in Rafah now feels like a suicidal idea. If the strikes don’t kill us, famine and lack of medical treatment might.”

A refuge under attack

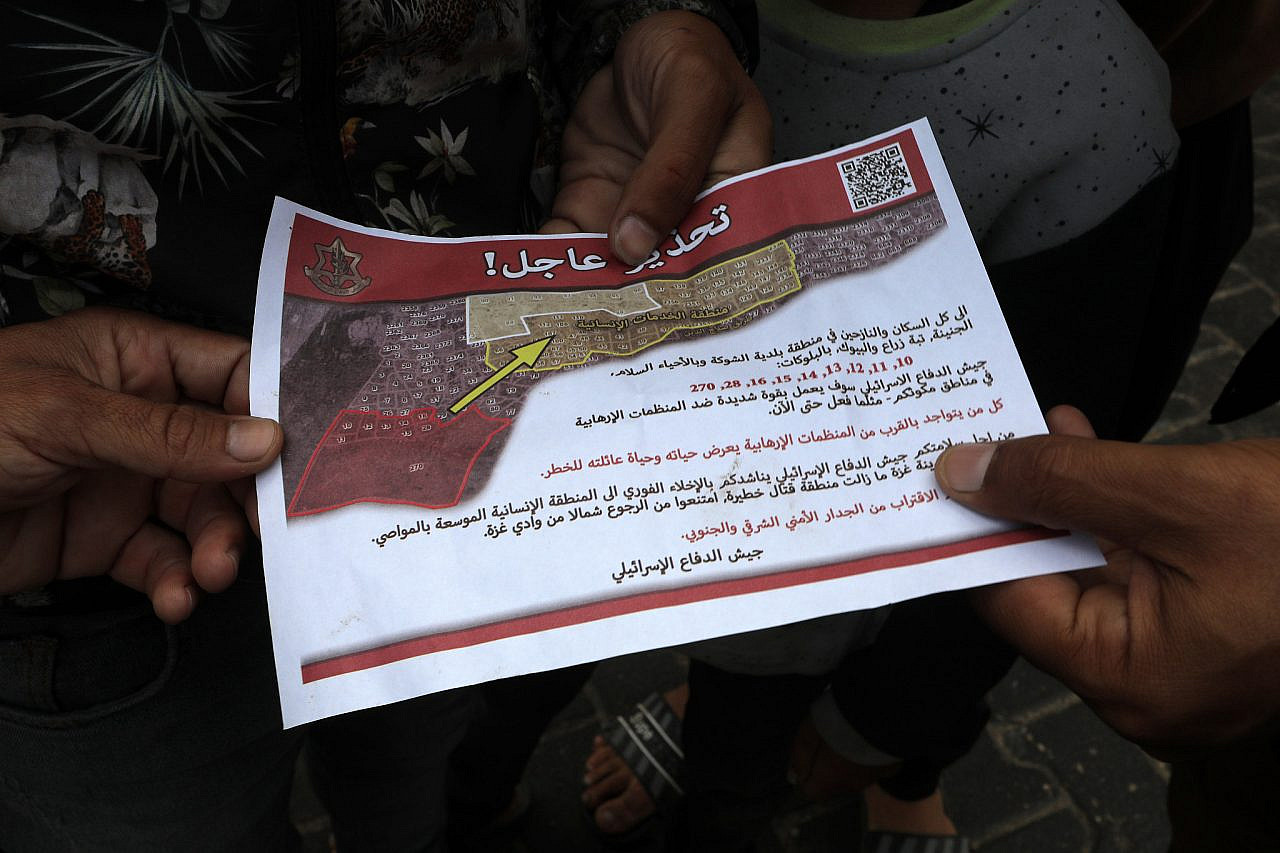

On May 6, Hamas announced it had accepted a ceasefire deal proposed by Egypt and Qatar. But the following day brought a stark reversal: Israel dropped leaflets on Rafah ordering the residents of its eastern areas to evacuate, in preparation for a ground assault into the densely crowded city. Palestinians flooded into the streets of Rafah, old and young alike, carrying their belongings on animal carts, looking for yet another shelter.

Since then, nearly 1 million Palestinians in Rafah have been displaced yet another time and most UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) shelters have been vacated, as people relocate to tent cities on the city’s western edge or try to return to Khan Younis and Deir al-Balah further north.

Just before midnight on May 26, Israeli airstrikes on a tent camp in the western Rafah neighbourhood of Tel al-Sultan killed at least 45 people. Two days later, another Israeli attack targeted an area where people were sheltering in tents in Al-Mawasi, west of Rafah, killing at least 21 more individuals.

By that time, the Israeli military said it had established “operational control” over the 8-mile-long border zone with Egypt, known as the Philadelphi Corridor.

The UN and other aid organizations have issued warnings that the closure of the Rafah Crossing is pushing every aspect of life to the brink. And as the Israeli military advanced into central Rafah last week, the last functioning hospitals have been closed and aid operations are being forced to shut down or leave the city.

Over the past month, Mahdi’s family struggled to survive, stripped of basic necessities and familiar routines. Clean water was scarce, gas reserves depleted, and the search for food and shelter was constant.

Telecommunication networks have also been down across the south since Israeli tanks entered the city, which has hindered emergency services. “Even if we could reach medical crews by phone,” Mahdi noted, “all they can offer is basic first aid.”

‘Each displacement feels just as terrifying as the first’

Eight days into the invasion, the family was forced once again to seek refuge elsewhere, joining more than half of the Strip’s population in search of safety that is nowhere to be found in Gaza. “This marks the seventh time we’ve had to leave our shelters [in Rafah],” Mahdi told +972.

The Mahdis joined those who flocked toward the city’s southern areas, erecting a tent close to the beach. Throughout the nights, explosions would light up the sky, with warplanes hovering ominously overhead. Venturing outside the tent, even to the makeshift toilet, became a risky endeavour as drones would target any movement after sunset. “We are terrified all the time, but nights are the worst,” Mahdi confided.

The arrival of a new day, however, brought no respite. In the scorching heat of early summer, the family still had to collect and burn wood to cook anything they could find, while facing the constant threat of bombardment. A few days passed, and what was once a bustling tent camp now appeared empty after Israeli forces reportedly claimed control of central areas in Rafah, dominating a significant portion of the city.

“When we fled northern Gaza to Rafah, we thought that was it. No more fear, no more death. But we have lived a reversed reality since then,” Mahdi said. “Each time [we’re displaced] feels just as agonizing and terrifying as the first — utter despair and terror.”

On May 21, the Mahdis made the difficult decision to evacuate their shelter in Rafah and head to Deir al-Balah in central Gaza. The family walked two kilometers before catching a bus with other evacuees, but when they learned the bus ride would cost about $70, they continued on foot, braving the presence of warplanes overhead. An hour later, a donkey cart passed by and they climbed aboard.

Most read on +972

Mahdi found no solace, however, in escaping Rafah alive: wherever they stayed, they would always be vulnerable to Israeli attacks.

“All we want is to be safe,” she lamented. “We want the world to recognize our humanity and our right to live in freedom and justice. We don’t know when this cycle of fear and death will end. All we know is that we are terrified and exhausted, and we long to return home and resume our normal lives.”