In my earliest memory of Ramadan, the Muslim holy month, my younger brother and I are splitting chores during the daylight hours. Too young to fast, we convince ourselves this is essential work. There is the trash haul or the corner market run. Pinning clothes in the afternoon sun. The occasional sweeping. But the day’s most important job comes just before twilight, when our Palestinian mother summons us to her busy kitchen.

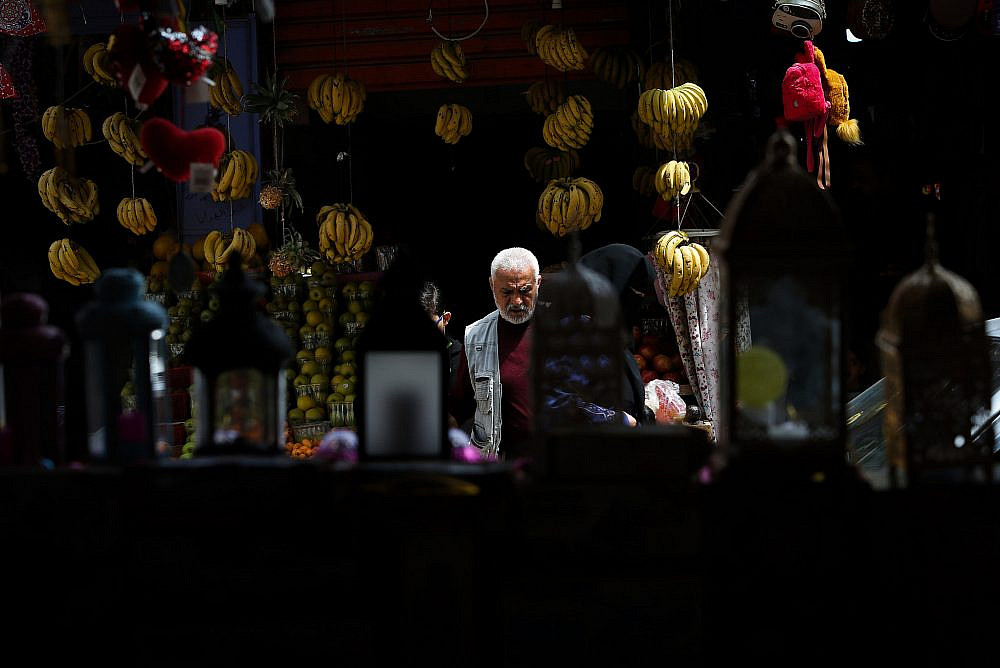

There, sworn off food and drink until sunset, she deputizes her boys as tasters. At her signal, we gauge the cumin in the lentil soup, pair sumac with lime in her bowl of fattoush, sweeten — if we must — the strained tamarind juice. My brother and I savor these tasks as we do the meal at sunset, for it is thanks to us that Mama’s iftar is, as it always must be, flawless.

Now, all the flavors are off. Among its more novel symptoms, the new coronavirus is said to block its host’s sense of taste. This is an especially cruel fate during Ramadan, when fasting, in the Muslim tradition, “is like a shield,” and the joy of breaking fast is second only to salvation. This teleological bargain — abstain now so that you may indulge later — is a familiar one in the Abrahamic tradition. But what use is it if we can no longer taste?

In our Palestinian home, the Arabic expression “ma ilha ta’ameh” (“it has no taste”) had nothing to do with food or the gustatory sense I thought my mother had perfected in me. Instead, my parents used the phrase to distance themselves from the world around them. Refugees from the 1967 Six-Day War, they had a habit of comparing most things in the United Arab Emirates, where my father had found work, to the Palestine that prefigured them. The sea at Dubai’s Jebel Ali, which was a serene port during my childhood, had nothing on Yaffa (Jaffa) and its Mediterranean breeze. The sunset, too, somehow fell short.

This dissociative state, now familiar to a world in lockdown, is the refugee’s underlying condition. For most of her adult life, my mother spoke of home in the future tense, a state of normalcy to which she would someday return. Eventually, as hope waned for a negotiated peace between Palestinians and Israelis, my mother’s expectation lapsed into a kind of earnest wish, kept alive through stories from her childhood, in a box of black-and-white stills, in the family kitchen.

This Ramadan, though, she has lost her appetite for nostalgia. Although she lives just two hours away, my mother is off-limits, her age and minor ailments leaving her especially vulnerable to the virus’s worst threats. So I call instead, trying to lighten her mood. When I complain that my own lentil soup lands flat, she counsels more salt, followed by a good squeeze of lemon.

“And make sure, ya mama, to drink it with a few green olives,” she reminds me.

I will remember, of course. We Palestinian children learned to heed our mothers’ wishes long before we understood the depths of their burdens, or the bitterness of their exile. Even though I could not share an iftar with her this year, I can still taste its pleasures. That, it turns out, is this Ramadan’s true blessing.