The Bund was a Jewish socialist, revolutionary party in Eastern Europe dedicated to class struggle. It is all but forgotten in modern day Israel, but a few members are still around to tell the story.

By Alon Aviram

A piano played and a middle-aged woman stood in the middle of the room singing classical Yiddish songs to an attentive, seated audience of 30 or so old men and women. Every so often the music was interrupted by a hoarse laugh or some remark blurted out in Yiddish by a member of the audience. Heavy red velvet curtains blocked out the now largely gentrified old Tel Aviv neighborhood of Nahalat Binyamin. At a social gathering every fortnight, members of this Yiddish community center escape the realities of 21st century Israeli life and return to a largely bygone Yiddish-speaking era.

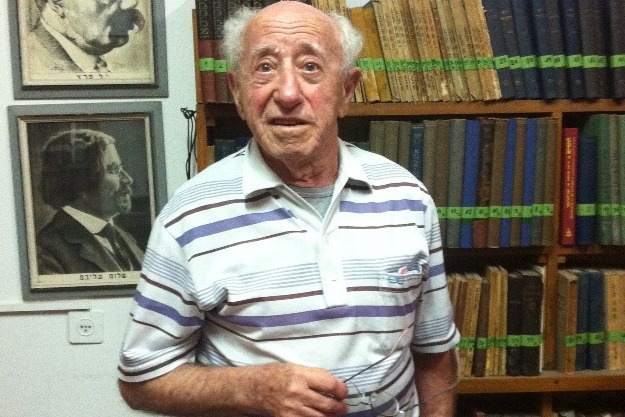

As the music finished and old friends said their goodbyes, journalist Yitzhak Luden, 90, one of the last surviving members of the Jewish Labor Bund in Israel, led me down a stairwell to a Yiddish library. “The others are here for just cultural and social reasons, they’re all too young to have been members of the Bund,” shrugged Yitzhak. As he pulled out tattered leather-bound books, he began to tell his story, and that of the Jewish Labor Bund. “One hundred and fifteen years ago, the Zionists held their first congress in a casino in Basel. The Bundists on the other hand, had their first meeting in the attic of a farm near Vilnius a month before. The Zionists were bourgeois from the start!” said Yitzhak.

The Bund was a Jewish socialist, revolutionary party, dedicated to class struggle and with an internationalist agenda. It played a significant role in the Russian revolutionary period. Similarly to Zionism, it was born in the wake of widespread anti-Semitism and pogroms across Europe. While the Zionist movement turned to emigration and the founding of a Jewish nation-state as a solution, Bundism argued that a Jewish state was a form of escapism which would only replicate existing class inequalities.

Yitzhak reconciled his position as an anti-Zionist living in Israel. “I came to Israel in 1948 not as a Zionist, but as someone fleeing war-torn Europe. Poland denied Bundists the right to organize, and the few Bundists who came made clear our political position in support of Palestinians, and for a one state solution.” The Bund in 1929 for example, defended the Palestinian riots as an anti-colonial uprising, rather than as anti-Semitic, as had been depicted by Zionists.

Even before the establishment of the Bund, a Yiddish article printed in Russia in 1887 wrote that those who think that “once the Jews have their own country they will be able freely to develop social ideas and cooperate with other peoples” forget that “the origin of nations is betrayal, robbery and murder”. The Bund would later echo this political position as an anti-Zionist organization with deep roots in the Jewish working class and intelligentsia across Eastern Europe.

“The religious Jews had traditionally organized Jewish communities. The Bund came out against both this and Zionism. It began to organize worker cooperatives and the social lives of many Jews. I was at first a member of the Bundist youth organization, SKIF. And some of my friends from SKIF who stayed in Warsaw later fought in the Ghetto resistance,” said Yitzhak.

(photo: Wikimedia Commons, PD-US)

The Bund repeatedly mobilized self-defense militias which managed to successfully thwart a number of pogroms, orchestrated general strikes, built a network of cultural organizations, and later became a considerable electoral force in Poland. As it turned to electoral politics in its later years, it obtained 40 percent of the Jewish vote in council elections across large cities in Poland in 1938. “That same year in Warsaw, the Bund took 17 out of 20 council seats won by Jewish parties in the Municipal elections” Yitzhak said proudly.

Decades earlier, Vladimir Medem, a Russian Jew, became one of the Bund’s most prominent theorists. He rejected the Zionist aspiration of establishing a Jewish nation-state. Medem did not however dismiss the value of national autonomy, but sought a version which was not territorially defined. Instead, the Bund called for the creation of a ‘state of nationalities’ rather than a nation-state.

The Jewish Labor Bund’s vision of national cultural autonomy was an early form of radical multiculturalism. It opposed both those who argued in favor of forced assimilation and those who called for nationalist separation. It envisaged a socialist society that would allow communities to freely conduct their own cultural affairs while ensuring that they remained connected economically and politically in one territory. Although the political conclusions outlined by the Bund were informed by life in late 19th and early 20th century-Russia, their commitment to essentially a one state model, of bi or multi-nationalism shares similarities with certain debates regarding the future of Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories today.

Despite the Bund’s influential role in early 20th century Eastern European Jewish life, it seems that they are solely remembered by specialist historians or nostalgic left-wingers. “No one imagined that the Nazis would do what they did”, said Yitzhak as he spoke of the Holocaust. As a result of the Bund’s insistence that Jews should stay and fight for socialism rather than emigrate, many were murdered by the Nazis, and to a lesser extent also by the Stalinists. Decades later, it appears that Zionism, the prevailing dominant ideology among Jewry, has played a part in forgetting, or at least in not remembering, the narrative of its pre World War II rival. Yitzhak, himself the survivor of a Russian gulag, said “we see this all around us. Before my wife met me, she had never heard of the Bund.”