Forty percent of Egyptians live below the poverty line; and many of them are factory workers like the ones in Shebin, a town two hours north of Cairo by car. Despite having played an active role in the events leading up to the deposing of Hosni Mubarak, they are still working full time for a wage that does not allow them “bread, dignity and freedom.” It might be a long time before they feel the benefits of the revolution; and meantime, they could be the ones who suffer the most from Egypt’s economic difficulties.

SHEBIN, Egypt — The town of Shebin el Kom is about two hours’ drive north of Cairo, in the Menoufiya Governate of the Nile Delta Valley. It has two notable institutions – a university, which was founded in 1976; and a textile factory, which was established in 1962. The factory’s 3,200 workers went on strike from March 6, joining workers in industrial areas across the country to demand a minimum wage and improvements in basic conditions like workplace safety, payment of overdue bonuses and severance pay for laid-off workers. We had heard that conditions were not good, and that there had been some violent confrontations with the army. The story seemed worth investigating, so we (a European journalist and I) drove out on the morning of April 6.

Factory workers played an important role in the January 25 revolution. They participated first as individuals, and later as organized groups. Workers from industrial towns like Mahalla started striking and organizing workers’ collectives several years ago. The April 6 Youth Movement, which was a primary organizer of the revolution, took its name from a Mahallah factory workers’ strike that was called on April 6, 2008 and then violently repressed by security forces. The April 6 Youth supported the workers’ right to strike under the rubric of freedom of speech and democratic values. But now that they had succeeded in overthrowing Mubarak, would the lives of the factory workers, who had been struggling for so long, change for the better?

Shebin turned out to be a dusty, noisy, shambling town that looked quite similar to a generic working class area of Cairo. Needing a coffee after a two-hour drive, we stopped at one of the traditional outdoor cafes on a main street, where men sat around low tables chatting or reading newspapers as they drank tea or Turkish coffee and smoked shisha. A few heads lifted as the two foreigners sat down, of course, but the reaction to our presence was pretty muted. We sat, ordered our coffees, and watched as cars and strolling university students passed back and forth.

At the next table, a middle-aged man wearing a nylon tracksuit and a baseball cap grinned at us, stretching his white, bushy, nicotine-stained mustache. He leaned over and welcomed us expansively, making it clear that we were on his turf, and proceeded to interrogate us, via our translator, in a genial but methodical manner. Where were we from and what were we doing in Shebin? Ah, journalists. And what newspapers did we work for? Yes, yes, he knew where the factory was. His brother was in charge of its security. Wait, drink your coffee, I’ll call him and have him come over to escort you.

Thirty minutes later, the brother was still “on his way,” and we were impatient. Just point us in the direction of the factory, we told the man with the bushy mustache. We don’t need anyone to accompany us. He was a bit put out, but insisted on paying for our coffees and directing us to the factory, which turned out to be about three minutes’ drive away – down the main road and to the right, at the end of a pleasant, tree-shaded residential street that was lined with low-rise apartment buildings.

The factory was huge and ugly, but the grounds were surprisingly well kept and clean. The place was also very quiet. There were no demonstrators and no soldiers; just a few workers milling around inside the fence, or sprawled on the grass. When they saw two foreigners approaching the gate, they sprang up and gestured for us to enter the factory grounds. We had the feeling they were expecting us.

A group gathered around us to air their grievances. They had a tendency to speak all at once and to shout, so it took awhile to sort out the background and the main issues. As is usually the case with factory strikes, the workers wanted higher wages, payment of long-withheld bonuses and, in the case of Shebin, re-instatement of workers who had been laid off without cause.

Once state-owned, the Shebin textile factory was privatized in 2007, when it was sold to some foreign investors that the workers called “Indians.” (Later, we discovered that they were referring to an Indonesian multinational group called Indorama, which serves huge companies like Nike and Adidas.) With privatization came a series of blows: most of the workers became private sector employees, rather than government employees; they lost most of their social benefits and subsidies; and their wages and bonuses were slashed or frozen. The new, Indonesian management introduced cost-cutting measures, laying off workers without cause and forcing those who kept their jobs to do the work of three or four people. Turning to the ministry of labor was a waste of time, they said; the bureaucrats had been bribed to disregard the workers’ complaints.

One man, well-groomed and wearing metal-framed glasses that lent him an air of authority, pushed his way to the front of the crowd. This was Yasser, the factory’s manager of imports and a graduate of Ain Shams University. Yasser knew some English, so he spoke to us directly rather than through the translator. He said he was 37 years old and had worked at the factory for 14 years. Smiling serenely, Yasser explained that everything was fine now. The workers had hammered out a great deal with the government, all their demands had been met, they would all be paid two months’ salary to cover the period they had been on strike, and they would go back to work the following day. Everything was much better because of the revolution, which they had all supported. Now, they had the right to strike and their grievances were addressed. Before, the security forces would have prevented them from demonstrating outside the factory grounds and their grievances would have been ignored.

Just then, the brother of the mustached guy from the café – the man responsible for factory security – showed up. He wore a white tie with black pin-striped suit jacket and smelled faintly of aftershave. Smiling without warmth behind opaque sunglasses, he shook our hands and stood close to Yasser.

“May we look inside one of the factory floors?” we asked. Sure, they answered. We’ll show you around. Come.”

The huge, fluorescent-lit space was filled with machinery and rows of fabric. We were told much more than we ever wanted to know about how to make synthetic fabric, and about the provenance of the machines. There was a space on the floor for prayer, with rugs and a wobbly cardboard mihrab indicating the direction of Mecca. The men who had been gathered around Yasser, the satisfied imports manager, bounded around the factory floor, chattering away in Arabic and gesturing for me to photograph the machines.

After awhile, I took the translator aside and asked a few of more reticent workers about conditions on the factory floor. It turned out that they were pretty bad. There was no ventilation, no air conditioning and no safety equipment. The bathrooms were filthy. People lost fingers to the manufacturing machines, they developed lung diseases from the synthetic fabric fibers, and they lost their hearing due to the noisy machines. There were no protective gloves, earplugs or face masks. The factory physician, they said, did not examine them properly when they developed work-related illnesses. They said he just prescribed superficial treatments for their symptoms and recorded that they could soon return to work. The factory owners, said the workers, bribed inspectors from the ministry of labor to ignore the safety violations. Had any of these issues been resolved with the new agreement? No, they answered.

Outside, while my European colleague, who speaks some Arabic, continued to chat with Yasser and a few others, the translator and I went looking for workers who might be less satisfied with the agreement.

Within about two minutes we came across a group of exhausted-looking men. They were dressed in worn galabiyas and cheap rubber sandals, and they pushed battered bicycles as they walked, slowly. “Are you satisfied with the agreement?” I asked. “No,” they answered. “But there is nothing we can do. We are not government employees anymore.” These workers had been privatized when the factory was purchased by Indorama in 2007. Since labor laws regarding severance and benefits are not really enforced in Egypt, they did not have the same benefits and leverage as Yasser, the satisfied imports manager, who was still a state employee.

One of the men told me that he was 54 years old and had worked at the factory for 40 years. He said that he worked seven days a week, and the other workers said they all worked every day. There was no day of rest. The man I spoke to had six children, and his take-home strike pay would be LE 900 (USD 150) for two months. “Is that enough to feed your family?” I asked. “No,” chorused the men; they all had large callouses on their foreheads, indicating that they prayed frequently and with fervor. “And how will you live?” I persisted. They rolled their eyes upward and said, “Ya rab.” God will help.

Just as they launched into a long list of grievances about the way management treated them, the security officer walked up, placed his hand on the arm of the worker I was interviewing, and suggested to the translator that we should continue our conversation outside the factory grounds.

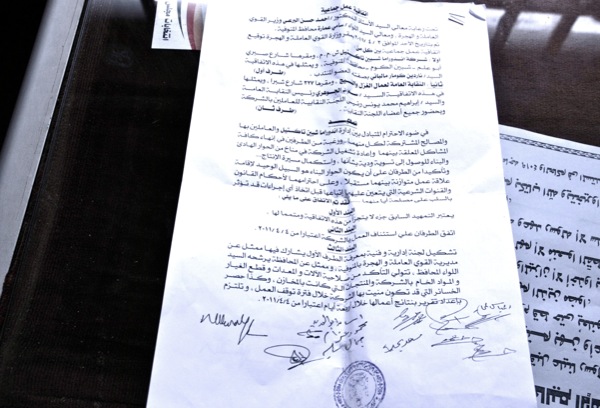

Over at the local branch of the syndicate, the governmental workers’ representatives, a reception committee was waiting for us again. Apparently, word about the visiting foreign journalists spread fast in Shebin. A group of men sat in an expectant row in a shabby but well-kept office that seemed to be little used. They tried to look nonchalant but busy; one man lifted the receiver of the phone, peered at the dial pad, punched a few keys, listened for a second without comment and then replaced the receiver. There were no filing cabinets and only a calendar for a wall decorations. The desk surfaces were clean. Tea and biscuits were served, and we were treated to another cadre-like speech. The agreement was excellent, the workers’ demands had been met, everyone was happy. The spokesman insisted on reading the entire agreement – which he just happened to have on hand. He even asked me to photograph it, page by page.

Difficult questions were stonewalled, but we did manage to confirm that a complex bonus system made it impossible for workers to avoid working on Fridays. They were not forced to work every day, but their base salary, which hovered around LE 300, was not a living wage. Friday bonuses made up the essential difference, and a few government subsidies picked up some of the slack. “And we break every day for prayers,” emphasized the spokesman, as we chewed on our sweet biscuits and sipped our tea.

I had a lot of time to think about the factory of workers of Shebin during the long, long traffic jam that eventually ended and spat us back into Cairo. Factory workers were not alone in earning LE 500 or less per month. Teachers and traffic cops made about the same, but teachers made most of their income via after-school tutorial schools, which are essential for public school pupils who wish to graduate; and traffic cops took bribes. By way of contrast, our translator was paid LE 1,000 for a day’s work with us. Factory workers living in an isolated industrial town had no marketable skills, and almost no possibility of earning extra income. They could look forward only to a lifetime of waking up each morning, working at the factory and taking home a monthly salary that put them at the poverty line.

An acquaintance that works for an NGO, which processes refugees from Eritrea, said that the monthly stipend for a family of four refugees was LE 1,100 (USD 184) – and that it was not quite enough for them to manage on. Another acquaintance, a diplomat and an expert in trade and economic matters, told me that there was absolutely no chance of the workers’ demand for a minimum wage of LE 1,200 per month being met. The government would go bankrupt, and foreign investment would dry up. This would exacerbate Egypt’s already grave economic difficulties. It was impossible. And if the factory workers did not go back to work, the economy would spiral even further downward.

Two nights ago, I celebrated the story of the Exodus of the Hebrews from Egypt. It is a story of escape from slavery, and it was told at a seder in one of Cairo’s last synagogues. For the first time in my life, I heard a seder leader, the person who reads the story of the Exodus from the Haggadah, tell us that we had once been slaves “here” (in Egypt), and not “there.” I thought about those factory workers again as I chewed on my first piece of matza, the Jews’ equivalent of Proust’s madeleine, and reflected, not for the first time, that there were still some people who lived in a sort of slavery, way down in Egypt-land – even though the pharaoh had been deposed and exiled to Sharm el Sheikh.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to make a payment toward reader-sustained freelance journalism, please click here. You will be taken to my old blog, where I have cross-posted this article. Scroll to the bottom of the post and click on the yellow ‘donate’ button.