Much has been written in recent years about the significant increase in the number of Palestinians learning Hebrew, a trend reflected across the Middle East as a whole. The reasons for this growth are diverse: economic need, the desire to “know the language of the enemy,” and intellectual curiosity. Even before the establishment of the State of Israel, and before Hebrew became the dominant tongue in the country, a small number of Palestinians — especially among the elites — took an interest in Hebrew, mastered it, and carried out translations from it.

The story of one of these scholars, Ribhi Kamal, illuminates the history of this small group of intellectuals. A native Jerusalemite, Kamal learned Hebrew in his youth at Jewish institutions in the city. He dedicated his life’s work to researching Semitic languages in general, and Hebrew in particular. Before 1948, Kamal used his knowledge to advance shared cultural-political activities between Jews and Arabs in Palestine; after the Nakba and his exile to Damascus, however, he began deploying his language skills in the Syrian intelligence service, against the State of Israel.

Why did Kamal devote his time to the study of Hebrew, and how did the place of the Hebrew language and the way it was used change after the establishment of the state?

Ribhi Tawfiq Kamal was born in Jerusalem in 1912, and studied at the city’s Alliance Israélite Universelle school. According to the testimony of another student at the school, the well-known Sephardi Jerusalemite Eliyahu Elyashar, Alliance served as a meeting place for young Jews and Palestinians. Members of Jerusalem’s elite Palestinian families, such as Ruhi al-Khalidi and Sa‘id al-Husayni, also studied at the school.

Kamal continued his studies in Cairo at Al-Azhar, a prestigious Islamic institution, and then trained as a teacher at Dar al-‘Ulum. While at Dar al-‘Ulum, Kamal studied Hebrew, Aramaic, and Semitic philology under the Orientalist Israel Wolfensohn (Ben-Ze’ev), a Jewish Jerusalemite who lectured on Semitic languages at the school during the 1930s.

Kamal was far from the only Arab intellectual who sought to study Hebrew. Other Arab scholars, who took part in the Nahda (or “Arab Enlightenment”) — a movement that sought to revive Arabic language and culture – also showed an interest; they saw Semitic studies, and in particular the study of Hebrew, as a way to trace the history of the Semitic peoples and to develop the Arabic language by identifying Arabic words with Hebrew or Aramaic roots. However, while most Arab students in Cairo studied Biblical Hebrew, Kamal also learned modern Hebrew — and it was this expertise that allowed him to understand, and take part in, the growing Jewish community in Palestine.

As a young student in Cairo, Kamal published Arabic translations of modern Hebrew texts in the Egyptian newspaper Al-Siyasa. He translated, for example, a short story by Isaac Leib Peretz, and parts of Hayim Nahman Bialik’s poem, “The Scroll of Fire.”

At the end of the 1930s, after returning to Palestine, Kamal used his Hebrew to call for cooperation between Arabs and Jews, whom he called “Semitic brothers.” Kamal, dubbed the “young Arab scholar” by the Hebrew press, engaged with both the Arabic sphere and the Jewish Yishuv. He trained Arabic teachers for Jewish schools, wrote for Arabic newspapers, and gave a series of radio lectures on both the Arabic- and Hebrew-language programs of the Palestine Broadcasting Service.

In 1941, Kamal delivered a lecture to an audience of around a hundred Jews and Arabs at an event of the League for Jewish-Arab Rapprochement and Cooperation, an organization advocating at that time a bi-national Jewish-Arab state in Palestine. There, he recited poems by Yehuda Halevi and Shaul Tchernichovsky in Hebrew, along with his own Arabic translations of the texts. Like many Jewish intellectuals of the time, he cited the golden age of Jewish-Muslim culture in Muslim-ruled Spain in the Middle Ages (Al-Andalus) as a political and cultural model for Jewish-Arab cooperation in Palestine at the start of the 20th century.

A profound rupture

However, the cooperation that Kamal worked to promote did not materialize. In the second half of the 1940s, Jewish-Arab violence engulfed Palestine and even reached Kamal himself: in December 1947, after the publication of the UN Partition Plan, the Histadrut-affiliated Davar newspaper reported that “irresponsible [Jewish] people set upon the young Arab [Kamal], who has many friends among the Jews.” Although the details of the attack are vague, it is clear that afterwards — as the war continued — Kamal arrived in Damascus with his family, and, like hundreds of thousands of other Palestinians, was uprooted from his city and his life.

The profound rupture Kamal experienced at this critical juncture in his life, and the upheavals in the society in which he grew up, led to his use of Hebrew as a sister language to Arabic and as an equal partner in a shared space becoming a thing of the past. In his new life in Damascus, Kamal applied his knowledge of Hebrew not to promote a shared Jewish-Arab society, but for a new purpose: to serve the Syrian government against the State of Israel. Just as the young Israeli government recruited Jewish immigrants from Arab countries to work in its intelligence and propaganda services, so too did Arab countries — especially Egypt and Syria — employ Palestinian refugees who knew Hebrew in their government services.

In 1948, Kamal began teaching Hebrew at the Syrian Defense Ministry, and he later worked as a lecturer in Semitic languages at Damascus University. He also served the Syrian government as a director and host of the Hebrew-language program on Radio Damascus, an initiative that began in 1952.

At the time, radio was often used as a tool of political resistance and psychological warfare; as the Egyptian newspaper Ākhir Sa‘ah stated, “the battle does not occur on land or in the sea; rather, its wide domain is the ether.” The State of Israel, too, invested heavily in Arabic-language broadcasts on the Voice of Israel, and it employed Arabic-speaking Jewish broadcasters such as Eliyahu Nawi and Maurice Shammas.

The aim of the Hebrew broadcast on Radio Damascus was, as announced on its first day, “to regularly explain to Jewish exiles in Palestine the truth of the facts and to provide them with information about details that malicious propaganda tries to hide and obscure.” Kamal and his colleagues tried especially to attract Mizrahi Jews in Israel to the program, and to persuade them to return to their countries of origin. During Israeli holidays, for example, they broadcast a Jewish prayer from a synagogue in Damascus and blessings from Syrian-Jewish leaders. The broadcasters even assured listeners that the prayers had been recorded in advance, so as not to desecrate the holy days.

They also interviewed Israeli “deserters” or “defectors,” as Jews who had fled to Syria shortly after arriving in Israel were called. The “deserters” spoke of the discrimination they experienced in Israel as new immigrants, and claimed the Israeli government was suppressing religion.

Most read on +972

During the radio program’s second week on air, Kamal used his Hebrew expertise to criticize how Israeli Jews speak Hebrew. “Not one Jew in a thousand speaks correct and pure Hebrew,” he said, arguing that this weakness in language reflects a weakness of the state. “The language is the nation: and if there is no language, there is no nation, and if there is no nation, there is no nationalism.” For Kamal, the correct and original Hebrew was that spoken in Al-Andalus during the golden age. It was Zionism, he claimed, that destroyed the language.

Hebrew as a weapon

Kamal’s fierce criticism of Zionism and Israelis on Radio Damascus raises difficult questions: did Kamal actually believe what he said on air? Did he lose hope for the possibility of a shared Jewish-Arab existence in Israel after the Nakba?

On the one hand, Kamal continued to address Jews directly over the airwaves, and he wanted to communicate with them at a time when there were no significant official diplomatic processes between Israelis and Palestinians. Kamal also continued researching the Hebrew language; he wrote books for learning Hebrew aimed at Arabic speakers, which are still used today.

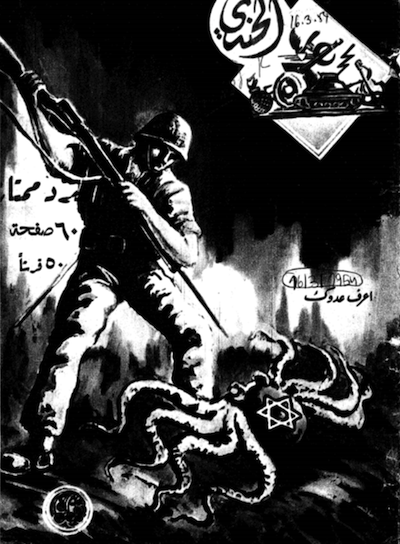

On the other hand, Kamal began to spread antisemitic ideas, both on the radio and in his writing. During one program, according to Davar, the host said: “Zionist propaganda is what invented the legend of the murder of six million Jews by Hitler and consequently succeeded in establishing a Jewish state.” In an article published in Al-Jundi (“The Soldier”), the Syrian Defense Ministry journal, Kamal referred to the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion” as an accurate and true historical source. Israeli journalists soon began to disparage him and treat the Hebrew broadcast from Syria as pure propaganda.

Kamal died in January 1979 at age 66. He left behind him a generation of Arabic students who studied Hebrew at universities in Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan, and who remember Kamal’s deep devotion to the Hebrew language. Kamal’s life story poses a challenge to the linguistic divisions wrought by the rise of Zionism and Arab nationalism in the 20th century, through which Hebrew was defined as a “Jewish” language and Arabic as an “Arab” language (spoken mainly by Muslims and Christians).

For Kamal, studying Hebrew was important not only to expose Arabic speakers to the language of their enemy, but also to enrich Arab and Muslim culture. In his books, he recommended that Arab scholars of the Arabic language learn Hebrew, or one of its Semitic sisters, in order to better understand the beauty of Arabic. He also quoted the Prophet Muhammad’s injunction to his scribe, Zayd ibn Thabit, to “learn the language of the Jews,” i.e. Hebrew, so that he could serve as his interpreter and help him understand the Torah and communicate with Jews.

But Kamal’s life story also reveals the fraught situations created by the linguistic division. Similarly to many Arabic-speaking Jews who, after arriving in Israel in the 1950s and ’60s, quickly realized that the most acceptable place for them to use the language of “the enemy” was in government services (and particularly the intelligence and propaganda services), so too did Kamal understand that he needed to find another way to use the language, for the Nakba had erased the shared Jewish-Arab space in which he had once spoken Hebrew.

Like the Palestinian writer Anton Shammas, who defined his writing in Hebrew as a kind of “cultural trespass,” so too might we understand Kamal’s work in Syria, and in particular with Radio Damascus, as a form of political and geographical trespass. Kamal used his fluent Hebrew to convey a clear anti-Zionist message to his listeners in Israel. He used his strongest weapon — his Hebrew voice — to oppose Zionism. The medium was the message.

A version of this article was originally published on the Social History Workshop’s blog, published on Haaretz’s Hebrew site.