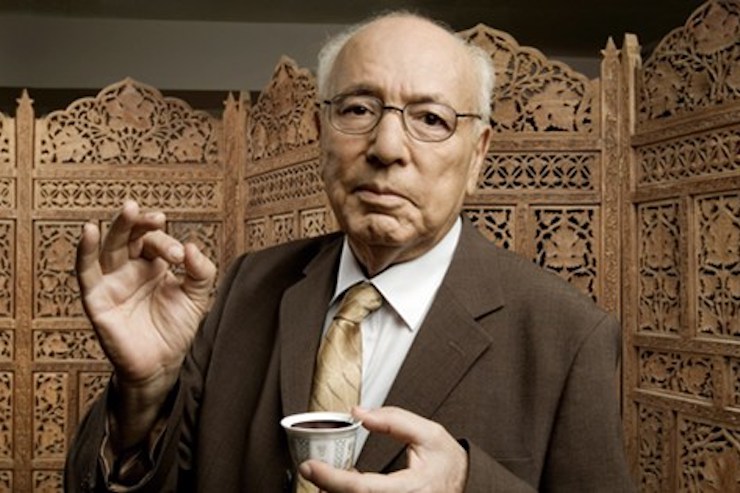

Born in Baghdad, Prof. Sasson Somekh was a prominent expert on Arabic literature, and a notable author and activist. He passed away this week.

By Raanan Shemesh Forshner

Prof. Sasson Somekh, one of Israel’s most prominent experts on Arabic literature and a lifelong proponent of peace, passed away this week in Tel Aviv. A winner of the Israel Prize, Somekh was a notable poet, author, translator, and activist.

Born in Baghdad in 1933 to an educated, secular family, Somekh developed an interest in Arabic culture at an early age, publishing Arabic poetry as a pupil. At age 17, he was forced to leave Iraq and arrived in Israel. The formative encounter between Arabic and Hebrew culture, and his decision to maintain loyalty to both, led him to form a connection between the two. “The task of mediating between the two great cultures, the two sister languages, has become his life’s work,” wrote Mizrahi poet and literary critic Almog Behar.

Somekh’s storied academic career often overshadowed his political biography. Shortly after arriving in Israeli, during one of his visits to the impoverished neighborhood of Wadi Salib in Haifa, he saw posters for the Israeli Communist Party (Maki). “Those posters astonished me,” he would say years later. “Although I knew that the Communist Party, whose representatives were already in the first Knesset, also participates in the elections, seeing such posters, and in Arabic, filled my heart with joy. I am from a country that not only prevents the left from acting openly, it also occasionally sends some of the leaders of this party – members of various ethnic groups, including Jews – to the gallows.”

On joining the Communist Party, Somekh wrote: “There was discrimination in every party aside from Maki, so I joined the party out of the belief that treating Arabs as second-class citizens is not the way to solve their problem.”

Alongside other Arab Jewish authors, poets, and artists who were also connected to the Communist Party, including Sami Michael, David Tsemah, and Shimon Ballas, Somekh continued to write in his mother-tongue in Al-Ittihad, Maki’s Arabic newspaper. Somekh also published in the Arabic literary journal Al- Jadid, which included other prominent Arab Jewish writers as well as Palestinian writers and thinkers like Emile Habibi, Tawfiq Ziad, and Mahmoud Darwish.

Like many other Arab Jewish writers who belonged to Maki, Somekh left the party during the 1960s, yet continued to encourage cultural exchange between Jews and Arabs while fighting against racism and working toward equality and peace. He gradually stopped writing in Arabic and began translating Arabic literature into Hebrew, while working his way up to becoming one of the top academics in his field.

“At every stage of my life, the fact that I am an Arab Jew benefitted me, it had a special place,” Somekh told Almog Behar in 2008. “Studying Arabic literature is not disconnected from my being Jewish-Israeli. It was very important to me to see and show how literature in our immediate surroundings is evolving, and largely in comparison with what has taken place in Hebrew literature. As you know, I have been translating modern Arabic poetry into Hebrew for 50 years, and this is my special angle as an Arab Jew who is an Israeli and deals with Arabic literature in Hebrew.”

Somekh told Behar that during his first years in Israel, the term “Arab Jew” was considered abominable. “The establishment viewed it as an unnecessary term, since in the eyes of the state the Arabs were enemies. Jews from Arab countries did not like being called this as well, for the exact same reason. That is, because it caused them to be associated with the enemy at present, an enemy that has a bad name in Israel, not only due to the fact that he is an enemy, but also due to the fact that he is not identified with progress and achievements, and even associated with the opposite. Thus, in Israel, ‘Arab’ is not considered a positive description.”

For Somekh, Arab Jew is a “cultural definition of a Jew who speaks Arabic and grew up in a Muslim environment.” In doing so, he wanted to emphasize that his identity stems from his point of view as a person who grew up in an Arab culture and continues to engage with that culture.

“The tendency among leading Mizrahi intellectuals of the younger generation to speak of themselves as Arab Jews is first and foremost a political position, that is, their desire to protest sharply against the sense of discrimination that they feel has been directed at Mizrahim. They are, in fact, seeking to highlight their reluctance to be part of the Zionist existence of the state. I do not have a problem with these positions, but for me this is not how the Arab-Jewish identity is defined.

He published two autobiographies, the first “Baghdad, Yesterday: The Making of an Arab Jew,” about his life in Iraq and the second, “Life After Baghdad: Memoirs of an Arab-Jew in Israel.”

“I am the last Arab Jew,” Somekh said, explaining his motivation to write his autobiographies. “That is why I wrote Baghdad, Yesterday: to document the life of a Jewish Arab child. Anyone who defines himself as an Arab Jew to attack others but who does not speak Arabic… does not count as such. While I do not define myself as a Zionist, if being Zionist means all Jews should come here, I am an Israeli patriot.”

A version of this article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.