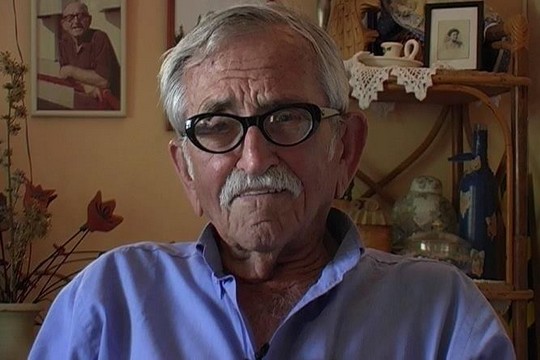

He was an officer in the IDF, a supporter of a bi-national state, and fundraised money to build a school in a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Until his very last day, Dov Yermiya remained a man of contradictions.

By Avi Dabach

Dov Yermiya, who passed away two weeks ago at the age of 101, was a man of contradictions. One of the one hand he was a venerated fighter of the 1948 War, on the other hand he exposed war crimes. One the one hand a tzabar who grew up in the heartland of Zionism, on the other hand a dissident. His life story is enough for two or three people. Not only did he live long, he also accomplished much. For better and for worse.

I met Dov in his final decade. A restless 91-year-old who amazed me and my film crew with his endless energy, and thought the documentary we were making on his life was hopeless, even though he enjoyed taking part in it immensely.

He was an incorrigible pessimist who saw the end of Israeli society for its sins, but in his deeds he was an optimist, almost disconnected from his sobering outlook. In this sense he remained a Zionist even when he strayed ideologically from Mapai’s Zionism of expulsions. He was a Zionist in the sense that he combined vision with forward-thinking, stubborn work without much recognition.

Dov was a Zionist, but also very connected to the reality in Palestine, and even supported a bi-national state in the 1930s. When the Partition Plan was accepted in 1947, he tried to convince his fellow kibbutz members to remain under Arab Palestinian rule. The war in 1948 changed everything, and Dov enlisted in the IDF, became an officer and was in charge of the conquering of several villages in the north.

WATCH: Dov Yermiya speaks about the conquest of Az-Zeeb

Dov Yermiyah was a very practical person. His actions followed from his very principled positions. Without actions, he believed, positions were bereft of meaning. That’s how it was in 1948, when he fought and was badly wounded in a battle over a police station, or a few weeks later when he speedily recovered and returned to the army — he heard a few company members talk about a rape that had taken place. Dov refused to whitewash or ignore the incident. Instead he interrogated his soldiers until one of them broke and admit that some of the soldiers gang raped a young Palestinian woman during the conquest of the village Az-Zeeb.

Kibbutznik, officer, rebel

In the remainder of the war — Dov saw initially saw it as necessary, though as it went on he came to see it as a result of the power-hungry military leaders of the young state — he encountered another horrifying crime: following the conquest of the village Hula on the border of Lebanon, he left his deputy to oversee the company and headed off to a staff meeting. When he returned to the village, he discovered that his deputy had ordered the murder of 35 men and teenage boys who were being held hostage. Dov opened an investigation and would not stop until the deputy was put on trial. His insistence to expose and investigate the crime led to threats against his life, and the army was forced to transfer him to a different unit. The deputy was sentenced to one year in prison alone.

Dov took advantage of his privilege as a man, kibbutznik, and officer not for the sake of personal or political capital, but to lend credence to his radical positions, his rebelliousness within his political camp — and after the First Lebanon War, outside it as well, when he first called on soldiers to refuse to serve and was kicked out of the IDF. In a book he published following the war, Dov compared the destruction he witnessed in Ein al-Hilweh to the destruction he saw when he fought in Italy in World War II.

Here, too, words did not suffice. He fundraised, bought caravans, and was able to convince the army to allow them into the refugee camp to serve as a makeshift school. A left-wing critique may view this as another case of “shooting and crying,” but for Dov there was no crying or confessions. Only a recognition of injustice and a desire to undo it. He did not ask what price he would pay for his deeds or who would join him, and often he was left entirely by himself with no support. But this did not matter to Dov — he felt that he had to act.

During one of my last visits to Dov I found a note on the door to his home that read: “To all my visitors — if I am sleeping, please wake me up.” Dov was and remained, until his last days, a man of action, who refuses to rest and let the world keep spinning without him.

Avi Dabach is a screenwriter and director. This article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.