The death of Soviet secret agent Marcus Klingberg is a reminder that even the most fiercely ideological spies can have a deep compassion for the societies they live in.

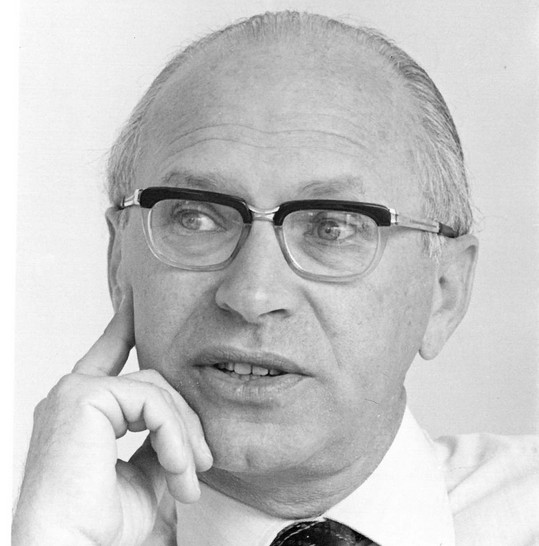

Marcus Klingberg, “the most damaging spy in Israel’s history,” according to Israel’s security services, passed away earlier this week at the age of 97.

Klingberg was a dedicated communist, the kind that blindly believed in the Soviet Union’s promises of the 20th century. He spied for the USSR for over 30 years and passed on secrets and classified materials to which he had access as the deputy scientific director of the top-secret Israel Institute for Biological Research (IIBR) in the town of Ness Ziona.

“He believed that his goal was to strengthen socialism in the struggle between the Western and Eastern blocs and not to harm Israel, even if it doesn’t sound convincing to the average Israeli,” says Attorney Michael Sfard, who served as one of Klingberg’s lawyers.

In his autobiography, co-authored with Sfard, Klingberg describes how his spying was motivated by a fierce commitment to ideology, as opposed to what the Shin Bet originally claimed. Klingberg believed that for the sake of peace, the kind of knowledge that could be found in IIBR could not remain in the hands of only one side of the superpowers during the Cold War, and that only a balance of knowledge between the West and the East can protect humanity.

“My grandfather taught me a lesson in loyalty,” says Klingberg’s grandson, Ian Brossat, who serves as the deputy mayor of Paris on behalf of the French Communist Party. “I know that in Israel he is considered a traitor, but his entire life was dedicated to the Soviet Union. The Soviets gave him the opportunity not only to survive (Klingberg is a Holocaust survivor, h.m.), but also to fight the Nazis who massacred his family and people. He always remembered that.”

Klingberg’s book, however, describes how he was recruited as result of being dragged into the world of espionage by a member of Soviet intelligence, who worked out of the Russian church in south Tel Aviv and provided Klingberg with caviar sent to Israel through diplomatic mail.

The decision to work at a top-secret center dedicated to developing biological weapons, and the choice to disseminate the knowledge gained there to other states, looks strange to people who identify as socialists or leftists. But like Klingberg writes in his book, and like Sfard reminds us today, this is the point of view of the Left in the 21st century. In the reality of the previous century, between world wars and the Holocaust, between two superpowers fighting one another using global espionage networks and proxy wars — the decisions made by left wingers were different, and actually made sense in the context of the time.

Born in Poland, Klingberg spent his entire life involved with the Eastern Bloc, and was very concerned with the regimes that sprouted there following the fall of the USSR. When I met him in Paris several years ago, he told me that of all of Israel’s policies, the strangest and most shocking were the country’s ties with nationalist and often anti-Semitic regimes in former Soviet countries.

It was exciting to see and hear that a man who had been convicted of espionage, who was arrested, interrogated, put on trial, and jailed in secret, who sat 16 years in prison and another number of years under house arrest (during which he was forced to pay his jailer’s salaries), and who left the country at the end of the 1990s — still reads Israeli papers on a daily basis. It was clear that Klingsberg was saddened and worried over the direction the state has taken. Patriotism, it seems, can take many forms.

A Pole and a Moroccan walk into a prison

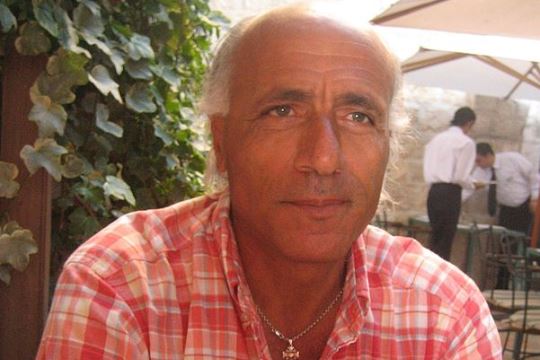

Klingberg’s death is a good opportunity to compare the fate of a biological spy with that of an atomic spy. There is much in common between the two, although things turned out quite differently for Mordechai Vanunu, who after working as a nuclear technician in the Negev Nuclear Research Center, revealed details of the country’s nuclear weapons program to the British press in 1986. Both acted out of a deep ideological commitment, both were communists, and both believed that they were furthering world peace.

Both were also arrested in complex operations. Both were sentenced to life in prison, and both were put under strict restrictions following their release. The difference is that Klingberg’s sentence was commuted, the security establishment did not harass him following his release, and he was able to leave the country and spend 17 years with his family in Paris.

Vanunu, on the other hand, was released over 11 years ago, and yet he is still subject to state persecution and severe restrictions on his movement.

“Klingberg’s treatment by the authorities had an important boomerang effect. Among other things because of his age and his health, and perhaps because he was Ashkenazi, the public feeling was that the authorities were going too far,” says Sfard, who until this day represents Vanunu, to +972. “This is the important background that allowed the court to put Klingberg to house arrest after his release, and also, I believe, to help stop the authorities from preventing him from leaving the country. The same compassion that many in Israel felt for Klingberg simply does not exist in Vanunu’s case.”

Like Vanunu, the Director of Security of the Defense — responsible for the security of the Defense Ministry, Israeli weapons industries and institutions in dealing with development and production of weapons of mass destruction and defensive centers — said that Klingberg “knew something that he did not know he knew.” He was prevented to speak to anyone apart from 11 people who were previously approved by the Director of Security of the Defense — and only on specific topics — and he was prevented from speaking in Yiddish so that his guards could ensure he was not speaking about forbidden subjects. “This is how he lived for around four years. And after four years everything passed and he was able to travel to Paris, and the sky didn’t fall,” adds Sfard. “He was punished out of revenge and out of creating work for the Director of Security of the Defense. So that the department feels important.”

But Marcus Klingberg was a Pole. Mordechai Vanunu is Moroccan. If Klingberg was able to garner public support, and even Shin Bet head Yaakov Perry volunteered to help him, there is almost not a single person who worries about Vanunu’s fate. Only at the beginning of the year did Israel’s High Court, once again, allow the state to continue abusing him, by preventing him from leaving the country and living with his wife abroad, not to mention having any kind of relationship with foreign citizens — forcing him to live a mostly solitary life.

“The authorities treat Vanunu with the same vengeful cruelty, despite the fit that as opposed to Klingberg, Vanunu never took part in espionage. Vanunu did not pass on information to a foreign country, but rather revealed information he thought every Israeli should know to a foreign journalist,” Sfard sums up. “The authorities continue to incite against Vanunu and demonize him in order to continue to abuse him. Unfortunately, if in Klingberg’s case the Director of Security of the Defense discovered there were limits, Vanunu’s case teaches us that anything is possible.”

This article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.