The violence unfolding across Palestine-Israel over the past four months has been accompanied by a near-real-time deluge of information on social and news media worldwide. As with other fast-moving, politically charged situations, a portion of that information has been false, and fact checkers have had their hands full. And as on other occasions, platforms such as Meta, Twitter/X, and even Telegram have been criticized for not intervening, or for intervening in a biased way.

Humans, however, do not formulate opinions based on information, but rather with stories spun from information — and the relationship between them is far from linear. Fictitious information can be arranged into a story that conveys profound truths, as great novelists have proven for centuries. Conversely, and as the past several months of coverage have demonstrated, there is no fact that cannot be indentured into the service of a lie. Beyond disinformation (trafficking falsehoods), I worry as a media researcher and longtime scholar of the Palestinian struggle that decontextualization (selectively presenting truths) is the more ubiquitous and elusive threat to our collective understanding.

Disinformation involves lying by commission, such as by asserting that the 2020 U.S. presidential elections were rigged against Trump, or that ivermectin cures COVID-19. Decontextualization, on the other hand, is all about lying by omission, and psychologists have shown that humans lie by omission with greater facility than by commission. Moreover, omission’s signature characteristic is absence — something humans are notoriously bad at noticing, which means we are liable to amplify decontextualized narratives unwittingly.

For inveterate observers of Israel-Palestine, though, the absences in the recent discourse have been egregious. While much has been made of the differential coverage of Palestinian versus Israeli suffering over the past several months, by far the greater asymmetry is to be found when comparing coverage of the weeks of kinetic violence after October 7 versus the decades of structural violence before.

The reason for this asymmetry runs far deeper than political agendas. News networks cover bombings, shootings, and other forms of kinetic violence because they are loud, finite events that seize our attention, invite investigation and intrigue, and whose victims can be counted, named, and mourned. By contrast, the everyday structural violence of Israel’s occupation and apartheid is comparatively uneventful. Instead of loss, it inflicts absence. Instead of killing, it simply aborts. Its first casualties are dreams and destinies. Even its victims cannot offer a full accounting, because how can you miss that of which you were always deprived?

Compared to kinetic violence, the uneventful, continuous, and illegible nature of structural violence renders it unfit for news coverage. Yet the two are inextricably linked. Decades of structural violence give rise to weeks and months of kinetic violence. To cover the latter while neglecting the former is, in a word, to decontextualize; to show audiences the symptoms while depriving them of the underlying causes. Without that context, audiences are more likely to see kinetic violence as unprovoked, stemming from innate and intransigent ideological commitments that necessitate a heavy-handed response.

In search of absence

All of the narratives spun by the Israeli government to justify its murderous bombardment of the Gaza Strip — including at the recent International Court of Justice hearing on the charge of genocide — draw centrally on the facts of October 7: that Hamas-led militants broke through the Gaza fence and, with intimate brutality, slaughtered over 1,100 people in southern Israel, most of them civilians, and took around 240 others hostage.

The narratives that “Hamas is ISIS,” that Hamas is morally irredeemable and strategically irreconcilable, that coexistence is impossible, that Hamas must be eradicated, that Palestinians in Gaza themselves will be thankful for this — all of these dubious narratives are lent authenticity by the undeniable horror of October 7. In this sense, these are narratives not of disinformation, but decontextualization. And while there have been some embellishments that have rightly drawn scrutiny, the core facts about what happened on October 7 are true, withstand fact checking, and are awful enough in their own right as to offer prima facie credibility to Israel’s war narratives.

The deficiency of the Israeli government’s narratives is not so much to be found in the information they present, but rather in the information that is left absent. Countering decontextualization is about seeing absence “with all its instruments” (to quote Sinan Antoon’s translation of Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish), seeing not only what is presented but what is left out, and letting silences speak. As Darwish would say, we must pull up some chairs for the ghosts.

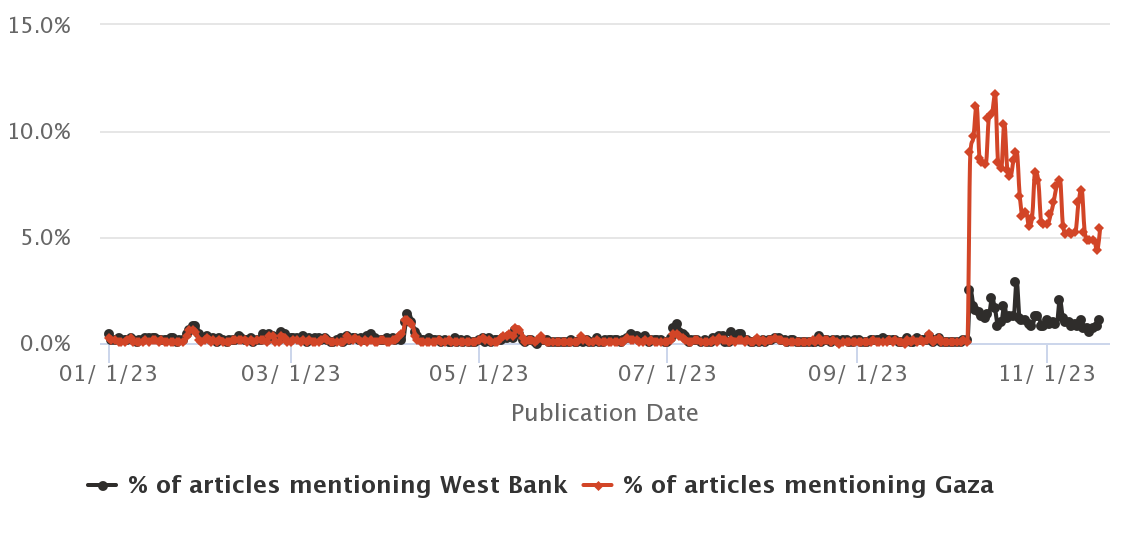

The ghosts start to emerge when you look at news media coverage in aggregate. MediaCloud, run by a consortium of universities in the Boston area, has tracked news worldwide for over a decade. Querying the MediaCloud database via their web interface, I found all news articles published by American, Canadian, or British news outlets during 2023 mentioning either “Gaza” or the “West Bank”, and generated the following chart.

In the chart, two curves are depicted, one red and one black, representing the percentage of news articles mentioning “Gaza” or “West Bank,” respectively, published on each day from the start of 2023 to just before the temporary ceasefire in late November.

This chart suggests that the occupied Palestinian territories are covered by the news when and where there is kinetic violence — that is, bombing, shooting, stabbing, and so forth. Most notably, the coverage of both Gaza and the West Bank after October 7 dwarfs everything published in the comparatively stable nine months preceding it. The coverage of Gaza after October 7, meanwhile, consistently exceeds that of the West Bank, where kinetic violence was also happening but at orders of magnitude below its sister territory.

I say kinetic violence for the sake of distinguishing it from its complementary concept of structural violence. Whereas bombings or shootings are examples of kinetic violence, structural violence is exemplified by walls, barbed wire fences, or systems of discriminatory laws. When a bomb goes off, it is a discrete event that can be reported or remarked upon. Structures of violence, by contrast, are continuous features that rend reality in two.

To get a glimpse of what it means for Palestinians to be the victims of structural violence, we can turn to the great Palestinian writer Ghassan Kanafani, who once wrote that “our lives are as a straight line that marches in shame and silence beside the line of our destiny; but the two lie parallel, and shall never meet.” To live in the shadow of a wall, or on the wrong side of a fence, or on the receiving end of a discriminatory system, is to live “in the presence of absence,” to be haunted by the ghost of one’s potential self — the person you would have become were it not for this wall, this fence, this law, this structure. In Kanafani’s telling, the life that Palestinians were meant to live haunts their every footstep. It runs parallel, and in full view of their imagination, a daily reminder and humiliation, next to which they trudge in silence and shame.

This is the agony of structural violence with which Palestinians were living throughout 2023, and for the long years and decades before that. But as the chart shows, news coverage only seems to tune in when there are outbreaks of kinetic violence. Why does structural violence get short shrift?

Firstly, structural violence is hard to measure, even for scholars with the time, resources, and expertise to do so. As Kanafani’s words suggest, structural violence can be measured by the gulf it creates between one’s reality and potentiality; between one’s current life and the life one could have lived were it not for this structure getting in the way. Such counterfactual analysis, however, is slow, painstaking, and statistical.

For example, using the West Bank as Gaza’s counterfactual, scholars have estimated the economic and political costs of the Gaza blockade since its imposition by Israel in 2007. While thoughtful, these interventions are complicated, take years to produce, and invite skepticism and disputation.

Even if you manage to measure structural violence in a credible way, however, the findings ultimately come off as overly statistical and hypothetical. Percentage-point declines in GDP or employment simply lack the visceral horror of a suicide bomb or airstrike. Behind those percentages are real people whose dreams have been crushed, and who may succumb to depression, substance abuse, and death many years before their natural time. But all of that is deemed so indirect, obscured, and probabilistic that it just does not resonate with audiences as strongly.

Decontextualizing kinetic violence

For all of these reasons, structural violence is a non-starter for news coverage. It is boring, expresses itself through absences, non-events, things that did not happen, realities that were not visited. News must sell itself to audiences, and audiences want to see action and be diverted. Kinetic violence is attention-grabbing, and so (as the chart above illustrates) it stands a greater chance of being covered in the news.

Action-packed kinetic violence then becomes the entirety of the story in our minds, through a defect of human psychology that Israeli psychologist and Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman calls the “WYSIATI principle”: what you see is all there is. Besides, in a world full of events, who has time to think about what did not happen?

The asymmetry with which kinetic violence is covered relative to structural violence has implications for how international audiences perceive Palestine-Israel and other civil conflicts. Though authorities may inflict structural violence on their subjects through a system of oppression (colonialism, apartheid, military occupation, and so forth), it is deemed not newsworthy, and receives only a modicum of coverage.

Eventually, after many years of daily indignities and frustration, a breaking point is reached, and a rebellion forms. The rebels are much weaker than the state, however, and cannot wield structural violence. Instead, their primary tool is kinetic violence. And because kinetic violence is newsworthy, the first time many outside observers really pay attention to the conflict is when they see masked rebel gunmen killing and terrorizing.

Indeed, if you analyze the patterns of rocket fire and airstrikes over the Gaza Strip in the 2010s, you will find over and over again that it is usually Palestinian militants who appear to break the “calm.” And yet, buried in the confidential UN security reports from which those findings were derived, nearly every rocket attack was preceded by Israeli provocations — bulldozing orchards, revoking work permits, and so on — that fell below the threshold of newsworthiness, and blended into the day-to-day humdrum of structural violence.

Outside observers do not feel the weight of the years and decades of structural violence that precede each moment of kinetic violence. This is what it means for the latter to be decontextualized: robbed of its structural provenance by human inattentiveness, by our incapacity to see absence, and by the unwillingness of the media to report what did not happen.

But the kinetic violence of October 7 cannot be understood without the structural violence of Oct. 6 and all the days before. If you recklessly burn fossil fuels for decades, there will come a time of hurricanes and wildfires. And if you indefinitely postpone the political process of relieving structural violence, you risk outbreaks of kinetic violence.

Hamas itself was founded 40 years deep into the Nakba and the ensuing Palestinian refugee crisis, and 20 years into the military occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. It is the enraged orphan of oppression, the product of a pattern so familiar to scholars of civil conflict that it is astonishing we still bother with proper nouns. Think of it as a law of conservation: violence is neither created nor destroyed, merely converted from structural to kinetic.

Most read on +972

That causal interplay, however, is lost on most audiences. In the wake of October 7, activists and commentators have heroically attempted to fill in the missing context extemporaneously, in lengthy Twitter threads or on television in the fleeting moments offered to them by news anchors. But a century of structural violence can scarcely be recited let alone absorbed under such constraints, even as events on the ground dramatically unfold.

The chart above shows, moreover, that the half-life of coverage for a crisis even of this magnitude may only be as little as six weeks. As the author John le Carré wrote, “history never stops to take a breath,” and people’s attention moves on to the next item, and the next.

For all of these reasons, decontextualization is an enormous challenge to our understanding. To undo decontextualization will require more than fact checking. We will need econometrics and media observatories. We will need to read the works of Palestinian novelists and Israeli psychologists. We will need compassion and patience, and to reflect upon our own biases and blindspots. We will need all these instruments to see absence.