To the Palestinians she defended in military courts, she was known simply as Tamar. Often dressed in black, she was instantly recognizable by her short-cropped white hair, glasses, and her ever-ready smile that would often give way to a chuckle. Tamar Pelleg-Sryck was a lawyer, a fierce human rights defender, a principled opponent of the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, and a wonderful human being whose drive, intellect, and youthfulness never strayed, even in old age. On March 11, Tamar passed away at the age of 97.

I deeply mourn her passing, as I am sure do hundreds of Palestinians who have experienced the injustices and indignities of incarceration, interrogation, torture, and administrative detention, but who had Tamar defend them, as best she could, against the court system that is integral to the occupation.

I first met Tamar in the Megiddo Military Prison, where I was sent after receiving an administrative detention order in December 1995. In those early days after the signing of the Oslo Accords, the newly-installed Palestinian Authority was beginning to take control of the larger Palestinian cities in the West Bank. Before ceding that control, Israel started detaining outspoken opponents of the accords without any charges, branding them “enemies of peace.” As the number of these administrative detainees surged, Tamar started taking on some of their cases, including mine.

I cannot recall the precise details of our first meeting. In my hazy memory, it was a brief encounter on a cold, gray day, with the usual exchanges that take place at such meetings: news about family, initial thoughts about appealing the detention order, and questions about prison conditions. Tamar had initially hesitated to take my case, and so — not yet knowing her — I wasn’t sure I wanted her to be my lawyer.

But the more Tamar visited, the more we talked and got to know one other. The cold of that first day transformed into interpersonal warmth, grounded in mutual respect and genuine human connection. The visits grew longer as time went on. Tamar started bringing me books from her personal library. Both the long conversations and the books transported me out of the prison environment, with its brutal and degrading routines. Writers like Nadine Gordimer, Hanna Lévy-Hass (the mother of Haaretz journalist Amira Hass), Paul Auster, Jacobo Timmerman, William Styron, William Trevor, and many others kept me company, all of them brought to me by Tamar.

Reading “The Confessions of Nat Turner” — Styron’s novel that describes the 1831 slave rebellion in Virginia — as I chased the ever-shifting light of the guard towers late into the night to devour a few more pages, was an experience of such profound joy and beauty that it now erases all other memories of that prison. What remains for me is that indescribable, mysterious elation a book bestowed on me in that moment, which I will forever associate with Tamar.

Some of the books and magazines Tamar brought for me would disappear before I was able to read them. Tamar would grow furious at such “security” measures and would stage a showdown with the Megiddo authorities, extracting from them a commitment to ensure that every single scrap of paper would reach me. Young soldiers, acting as censors, were tasked with checking books to determine which were permitted. They often — literally, and sometimes amusingly — judged books by their covers, but Tamar’s agreement with their superiors meant that, at the very least, they could no longer treat any of those books disrespectfully or throw them away, even the ones they deemed dangerous.

A Jewish-Israeli pessoptimist

The unique skillset Tamar brought with her — compassion, drive, and an appreciation of literature — is perhaps due to the fact that she was a teacher and organizer long before she became an attorney at the age of 61. The remarkable decision to enter the field of law at that age is key to understanding Tamar’s personality, her boundless energy, and the lengths she would go to in order to rebel against injustice.

In her determination to defend Palestinian prisoners in a hopelessly biased military “justice” system, this Jewish-Israeli woman was Palestinian to her core, with the indefatigable spirit summed up by Emile Habibi’s “pessoptimist”: someone who accepts their painful reality but refuses to give up and continues to fight, hoping against hope — a seemingly contradictory position we, as administrative detainees, had to learn as well. Tamar rejoiced in the small victories we were allowed, such as the authorities’ concession to allow books into Megiddo, but she never lost sight of the bigger picture.

Tamar was instrumental in my unlikely release, which she helped secure after 20 months of successive military detention orders. She encouraged me to write and took it upon herself to ensure that my words reached people beyond the prison walls. Unsuccessful appeals to the military courts — and even one to the Supreme Court — did not deter her.

Her joy at showing me a draft article that Serge Schmemann, the head of the Jerusalem Bureau of the New York Times, had written about me (“It will appear on the front page of the Times,” she told me proudly) was not diminished after an editor at the paper mysteriously decided to kill the article. Ultimately, the Supreme Court ruled in August 1997 that I should be released to four years of exile. While I was in Ramleh Prison, waiting to leave for the Netherlands, it was Tamar who brought me a suitcase, a Palestinian passport, news from my family, and information about when I would finally be allowed to leave.

Most read on +972

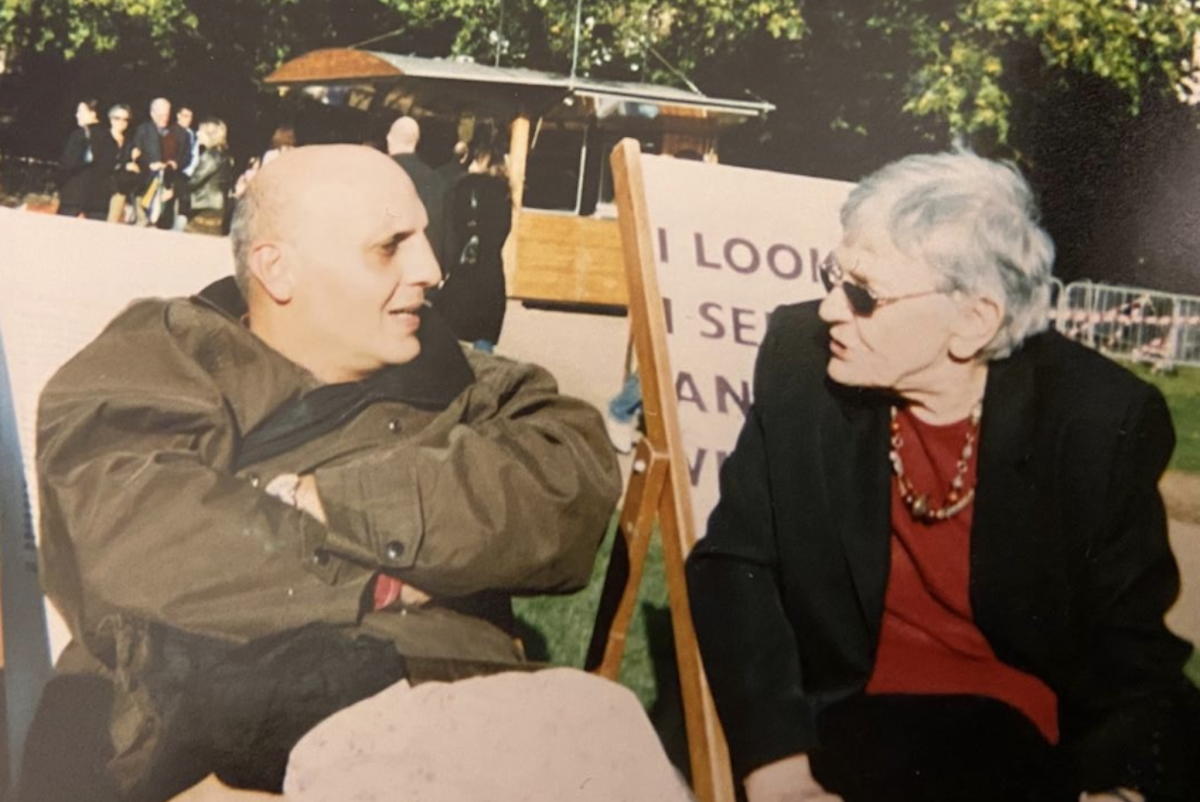

In freedom, Tamar and I met a few times, together with my wife and children: in Rotterdam (where her daughter lived) and the Hague (where I lived), in Paris, and in London. We spoke regularly by phone and corresponded through emails. She was always her energetic and curious self, a headband crowning her white hair, and working all the time, living all the time. We eventually lost touch, but that did not diminish the depth of my feelings of love and respect for her.

In one of our conversations while I was in prison, Tamar said of a woman she knew: “She wrinkles beautifully.” Though she was describing her physical appearance, I believe that how one wrinkles may be a reflection of their soul. As she grew older, Tamar kept wrinkling beautifully, never losing her moral purpose.

For me, as a Palestinian living in this moment of genocide and rampant hatred, mourning Tamar’s death serves as a reminder of the faith Palestinians and Israelis opposed to the occupation must maintain: that one day, no matter how distant, the occupation will end and justice will arrive.

An abridged version of this obituary was first published on the LRB blog. Read it here.