It’s no coincidence that images of the Tower of David are popping up everywhere in the holy city: right-wing settlers and real estate moguls alike have been using the symbol to gain power.

By Dana Hercbergs

Like mushrooms after the rain, the Tower of David seems to be popping up in new places in Jerusalem. Its appearance on phone books, municipal pamphlets, and items like sugar packets and votive candles strikes me as a phenomenon of the last few years, having lived in Jerusalem off and on since 2007. Local friends do not seem to think much of it, claiming that the structure has been associated with Jerusalem for some time—what is referred to as the Tower of David is a 17th century Muslim minaret located inside the Citadel, by the Old City’s Jaffa Gate.

In 1989, the Tower of David museum opened for the public, and is a popular place for tourism and cultural events. Perhaps the change is more noticeable in real-estate development, especially around the Green Line. In Mamillah, near the corner of Agron and King David Streets, recent high-profile projects—King David Residence, Mamila Kfar David, David’s Citadel Hotel, and Alrov Mamila — make visual or semiotic reference to King David or to the Tower. Visible since the mid-2000s, the rebranding of the area is implicated in attempts to erase traces of the border through upscale development that appeals to an international clientele.

Even real estate projects elsewhere in the city seem to draw on the symbol of the Tower, or amplify its iconic status. A billboard ad for a residential scheme named Lev Ha-Ir, located decidedly away from the Green Line in West Jerusalem—between Beit Hakerem and Givat Mordechai—in 2013 featured the icon beside that of Shrine of the Book (Heikhal HaSefer) museum, where the Dead Sea Scrolls are housed. This November, brochures for HaBayit B’Yerushalayim (A House in Jerusalem)—an exclusive apartment complex for retirement-age residents on Hebron road—were left in my building. They featured photographs of Jerusalem locations, including a view of the Tower, but not the Western Wall, an equally (if not more) recognizable landmark.

What accounts for the increasing appearance of the name David and the eponymous Tower, particularly in place of other familiar symbols? And what does this “Davidization” say about current political realities in Jerusalem?

Throughout the centuries, Jerusalem has been represented through various structures that have, in turn, mobilized religious, orientalist, and colonial motivations. In our image-driven era, political power is increasingly invested in image management: struggles over the physical area of Jerusalem are likewise manifested in attempts to control the city’s visual representation, as led by the tourism and real-estate industries, and also by the municipality. Since the demise of the peace process in the 1990s, and especially after the Second Intifada, Jerusalem appears to be undergoing a shift in branding, with the Tower of David eclipsing other classic symbols of the city. In Israel, this repertoire includes the Dome of the Rock and the Western Wall, the Knesset, the large menorah sculpture outside it, as well as other notable landmarks like the Yemin Moshe windmill and the water fountain of the lions (referencing the Lion of Judah, the municipal emblem).

This has not always been the case. Among the aforementioned images, the most prominent have been, since 1967, the Dome of the Rock and the Western Wall, often comprising a dual image. Following Israel’s conquest of East Jerusalem, they signified Jews’ access to the Western Wall after nearly 20 years. In the decades since, as former Mayor Teddy Kollek created Jewish settlements in annexed areas of East Jerusalem, the Dome of the Rock/Western Wall image persisted despite the high visibility of the Muslim structure.

The shift towards a more exclusive conceptualization of Jerusalem in terms of Judaization and division began with Kollek’s retirement in 1993. With the concurrent decline of the Oslo peace process, Israel’s embrace of right-wing ideologies has led to unilateral actions (e.g. the separation barrier) and disengagement from peace negotiations with the Palestinians. At the same time, the liberalization of the economy has enabled capital to increasingly mobilize ideology in Jerusalem, particularly beyond the 1967 borders. These forces—ideological and financial—together promote Israeli Jewish demographic and spatial dominance in the city.

In line with these developments, perhaps the best example of the prominence of David’s sign is the highly-charged City of David national park, whose fantasy is the revival of a Judean Kingdom. Located in the dense Palestinian neighborhood of Silwan, just south of the Old City walls, the archaeological park is a popular tourist site, especially among Israelis. The signs and tours there narrate primarily the Jewish ethno-national past, glossing over archeological and contemporary presence of Palestinian and other cultures. It is the first national park operated by a private settler organization (Elad—acronym for “to the city of David”), with Jewish settlers living within it since the early 1990s. A recent report by the NGO Emek Shaveh reveals that the government’s financially supported Elad’s activities in Silwan in the late 2000s.

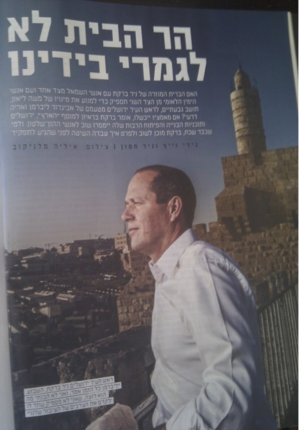

Jerusalem’s transformation into a religious and ethno-national capital radiates from this place. The structures around the Green Line play on their proximity to the Tower of David, the historic King David Hotel up the street, and perhaps also David’s Tomb on Mount Zion, the closest sacred site to Western Wall on the Israeli side of the Green Line, where Jews were able to make pilgrimage after 1948. Certainly, David has been appropriated as a symbol for luxury in Mamillah, where high-end hotels and residences greet tourists on their way to the Old City. But it is also permeating everyday local consciousness: a Haaretz newspaper supplement published prior to Jerusalem’s mayoral elections in October 2013 featured incumbent Nir Barkat standing before the Tower, with the title “The Temple Mount is not yet in our hands.” The Tower had thus replaced the Dome of the Rock/Western Wall image as a stand-in for Jerusalem.

Does the Tower of David serve as a “safe” or secular alternative to the religious and contested site of the Dome of the Rock/Western Wall? Has the increased power and visibility of the settlers in City of David led to the wider appropriation of David’s symbol as a competing icon for Jerusalem? Or is it simply a useful marketing tool to attract wealthy foreign buyers?

There may be some truth to all of these conjectures. As a deep and longstanding symbol, the Tower of David has reappeared in different guises. What seems clear is that the current privileging of the icon and its namesake is implicated in a changing reality in Jerusalem, where ideology and transnational finance are increasingly shaping local perceptions of the city.

Dana Hercbergs, Ph.D. is a folklorist writing about memory and tourism in Jerusalem. She works in the organization Emek Shaveh.

Related:

In Silwan, the settlers are winning – big time

Formula 1 promo de-Arabizes Jerusalem skyline

Disturbing the ‘peace’ in Jerusalem’s holiest site