With at least 34 votes in the Senate, the Iran deal is a fait accompli. Netanyahu will continue to enjoy a reprieve from pressure about the peace process as a result of the diplomatic energy being spent on implementing the Iran deal and Obama’s efforts to push it through Congress. Israel will also, however, face increased pressure regarding its own nuclear arsenal as part of a renewed Iranian push for regional disarmament.

By Shemuel Meir

The discourse on the nuclear deal between Iran and the Western powers continues to change. Opponents of the agreement are waging a last-ditch attempt to present a “better deal in place of a bad deal” — but the community of independent experts on nuclear proliferation understand that the Vienna Agreement blocks Iran’s path to a nuclear weapon. Those who are not driven by ideological-political considerations understand that the deal does not temporarily freeze Iran’s nuclear progress for 15 years, but rather it establishes the country as a Non Nuclear Weapon State (NNWS) according to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). It is a deal that does away with the ambiguousness of Iran’s nuclear program over the last decade. The deal creates a new paradigm in which “there is no nuclear weapon in Iran” is the order of the day.

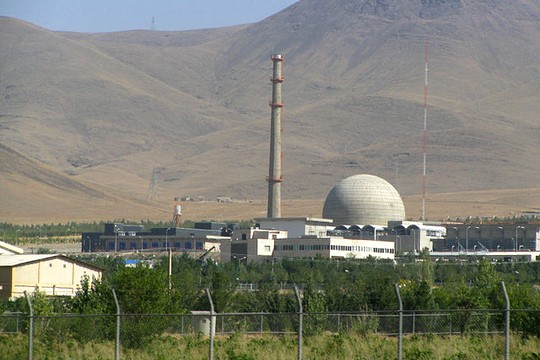

Over the past week, the deal’s opponents in the U.S. and Israel have attempted to take advantage of the public’s ignorance about the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in order to make it seem like the agency’s inspection regime relies on self-supervision by Iran. The story was a final, failing attempt to tear apart the heart of the agreement, which in reality is based on an intrusive monitoring regime. It must be noted that the IAEA is responsible for continuous supervision of every nuclear facility, including the Parchin military complex, through its special equipment.

Furthermore, every IAEA inspector worldwide was professionally trained in the Los Alamos National Laboratory in the United States, which is responsible for producing America’s nuclear arsenal. This means that the U.S. will be present, even if indirectly, in the monitoring delegations in Iran. According to the agreement, only inspectors from countries that have diplomatic relations with Iran will be able to enter, hence the re-opening of the British embassy in Iran and the re-establishment of ties between the two countries will allow British IAEA inspectors to take part. On the nuclear issue, like on issues of intelligence, the U.S. and Britain maintain a “special relationship” unrivaled across the globe. On these issues, the U.S. and Britain are strategic twins.

The discourse about Iran the day after the nuclear agreement touches on a wide range of topics: Iran’s regional position, its relations with “moderate” Sunni states, a possible détente with the U.S., the war against Islamic State, terrorism, Iran’s place in the Syria crisis and possible solutions to the civil war, and implications for the global energy economy. But let’s take a look at the direct consequences the deal will have on Israel.

The peace process. Despite the fact that this phrase has been erased from the lexicon of the Israeli government and the country’s centrist camp, there is such a thing. There are no indications that Obama plans to retreat from his outline for a sovereign Palestinian state on the basis of 1967 lines with mutually agreed upon adjustments, and that borders Jordan and Egypt. The intense negotiations on the Iran nuclear deal, however, have sucked dry the administration’s diplomatic energy for the time being.

We are now seeing precisely what the White House had hoped to avoid: an orchestrated campaign by Netanyahu, AIPAC, and the Republicans in Congress to thwart the deal. Because of the current battle over the Iran deal, Obama hopes that France will freeze its UN Security Council initiative to set a timetable for establishing a Palestinian state. But let’s be clear: he wants Paris to freeze the plan, not rescind it.

Exactly when the peace initiative resurfaces will be determined according to the detailed timetable for the nuclear deal with Iran. It isn’t likely to happen in the near future (Obama must first overcome the congressional hurdle), or at the UN General Assembly meeting at the end of September. According to the nuclear deal, the first stage Iran must pass in order to get approval from the IAEA is in mid-December — when the agency hands over its report on the past suspicions surrounding Parchin (until 2003, when suspicious military activity was halted at the complex). This will be the green light to gradually start removing sanctions in the spring of 2016.

What does that mean for Israel? The spring of next year will likely be the final days of quiet, during which no one asks the Israeli government about peace with the Palestinians. From that point on, President Obama will have 10 months to push forward his peace plan without having to deal with any political pressure, or at the very least revive the “Clinton Parameters.” In all likelihood the most Obama will be able to do is hope to pass on some process or progress on the Palestinian issue to his successor. Eliminating the Quartet’s condition of not speaking to Hamas would also help. If the president wants to base his plan on Saudi Arabia’s Arab Peace Initiative (API) based on ’67 lines (much like Secretary of State Kerry did), he will find that Iran is an indirect supporter. (The Organization of Islamic Cooperation, of which Iran is an important member, has endorsed the Arab Peace Initiative.) The new Iran may find it advantageous to present an outward appearance that is pro-peace, and maybe even support diplomatic efforts to mend ties between Fatah and Hamas. Iran has “something to give” the United States vis-a-vis Israeli-Palestinian peace — and it can get something in return somewhere else.

Nuclear disarmament in the Middle East. It is unlikely that the P5+1 forum (the five permanent members of the UN Security Council plus Germany) will be appropriate for Israeli-Palestinian peacemaking. But that doesn’t mean it can’t be useful for other regional goals. Two weeks after the Vienna agreement, Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif published a surprising op-ed in The Guardian, which spoke directly to the five declared nuclear powers with which Iran negotiated in Vienna. The headline said it all: “Iran has signed an historic nuclear agreement — now it’s Israel’s turn.” According to Zarif, the world must take advantage of the momentum created by the Vienna Agreement, which cements Iran’s status as Non Nuclear Weapon State, in order to create a worldwide initiative to ban nuclear weapons. This initiative will breathe new life into and complete the NPT. Zarif knows well that this will be difficult and complex. Thus, he proposes that the five nuclear powers begin taking a number of small, viable steps. Among the first of them: taking steps toward establishing a Middle East free of nuclear weapons, as well as other weapons of mass destruction.

Zarif’s surprising article flew under Israel’s radar. Adding new parlance that will one day be quoted in strategic literature, the Iranian foreign minister distanced himself from the typical Egyptian call over the past few decades, according to which “Israel must join the NPT,” and instead posed a new challenge to the nuclear powers: establish a Middle East free of nuclear weapons as soon as possible, as part of a global initiative. It appears that the Vienna Agreement might allow the new Iran to return and reclaim its place of leadership from the 1970s in everything having to do with regional nuclear disarmament. Zarif’s initiative is proof.

The paradigm of a “nuclear weapons-free Iran” obligates us to rethink a few things. Initial signs of the Iranian challenge could be found in President Rouhani’s speech at the UN. But the most important indications were on full display at the most recent NPT Review Conference in May of this year. At the NPT, Iran did not join the antagonistic Egyptian position, instead sending pragmatic messages to the American delegation that was attempting — and ultimately failed — to break the impasse between Cairo and Jerusalem. The Iranian delegation indicated to the U.S. that it sees a reciprocal link between its own nuclear deal and regional nuclear disarmament/non-proliferation.

The new Iran can be expected to take Egypt’s top spot in international nuclear forums, and to create new challenges and lay terra incognita for Israeli diplomats. This is likely the end of the duel between Egypt and Israel. Zarif is trying to put the discussion about regional disarmament on the table of the five permanent UNSC members, within the same framework that led to the Vienna agreement. Israel is likely find that its “Long Corridor” doctrine, of avoiding ever reaching the NPT, has exhausted itself. Iran is proposing abandoning the Long Corridor and the endless discussions about procedures and trust-building measures woven by Egypt and Israel — and opening a new door to regional disarmament at an accelerated pace. This is the new Middle East, Iranian style. The major unknown variable is the reaction of the United States, which in the past supported the Helsinki Conference on regional nuclear disarmament. The first test will be at both the IAEA meeting in Vienna and the UN General Assembly in NY this September.

Shemuel Meir is a former IDF analyst and associate researcher at the Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies at Tel Aviv University. Today he is an independent researcher on nuclear and strategic issues and author of the “Strategic Discourse” blog, which appears in Haaretz. A version of this article was first published in Hebrew. Read it here.