The J14 movement’s most significant achievements lie not in the political realm, but in the ways in which it has challenged and blurred commonsensical categories and distinctions involving space, time, language, and class. At the same time, one critical category remains as stable as ever

By Thom

1. This struggle is between order and disorder. This struggle is between the attempt to organize the world coherently and the challenge to this attempt, which reveals its inherent support of the social status quo. This struggle is about the power to destabilize that which is taken for granted, along with its constitutive binary oppositions. This is why this struggle is so totalizing, so exciting, so frightening. The predominant look on people’s faces during Saturday’s public demonstration was not one of defiance, nor of joy; it was awe. What was this thing? Where did it come from? What does it say about us? For, if there had been any comfort in the sense of helplessness to which we had become so accustomed in recent years, it was to be found in the fact that it was so familiar, so predictable. Good versus bad, the few against the many, omniscient “us” versus “them” who have been brainwashed. But where do we stand when, based upon all recognizable measures, it is “us” who appear to be a primitive, primal crowd?

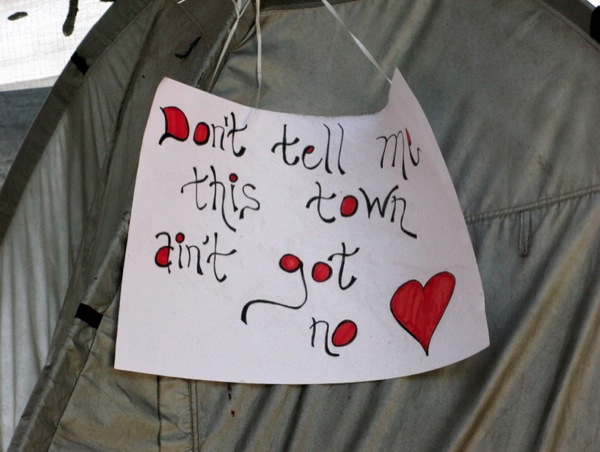

2. This struggle is about the blurring of categories. Its fundamental tactics are disruption and dissonance, accompanied by a playfulness that makes its messages easier to stomach, on the one hand, and simultaneously blurs the widely accepted distinction between “serious matters” and “fun” on the other. The struggle started out using a playful linguistic disruption based on a popular song intended to teach children the Hebrew alphabet. In the song, which follows the general pattern “A is for…, B is for…,” the first letter, aleph, stands for ohel (tent), and the second, bet, stands for bayit (house/home). These lexical markers were then switched in the protest slogan to form the discordant, playful bet ze ohel, or “B is for tent” – which it is obviously not. This was followed by the blurring of virtually every distinction and organizing principle we know. Spatially, the struggle challenged distinctions between private and public, home and the street, the personal and the political. This is the struggle where home and the semi-naked human body stepped outside and appropriated public space. It is certainly not coincidental that local opposition to the tent protest on Rothschild Boulevard focused on those instances in which the human body made its presence felt in its crudest, most corporeal form – by using local backyards as toilets, or by invading the seemingly isolated territory of local restaurants and cafés for the same purpose. Likewise, it is certainly not coincidental that one of the most common critiques targeted at the tent protesters is that their space is not political enough. The fact that they partake in everyday conversation, guitar playing, or simple game playing is perceived as an indication of the protest’s inauthenticity. It reveals our routine expectation that a public space used for political protest be exclusively devoted to politics and not “contaminate” itself with everyday matters. After all, a political protest is serious business; it is full of anger and pain. So what are all these witty slogans doing here? Why the carnival atmosphere? Is this protest disguised as a new age festival or a new age festival disguised as protest? “It’s fun protesting here” (kan mohim bekef) is a slogan (roughly translated) found on many tents, playfully parodying the prototypical sign found on many apartment doors in Israel and signaling young urban domesticity, “It’s fun living here” (kan garim bekef). Indeed, how can one take seriously those whose protest seems so pleasurable?

3. Spatial practices tell only part of the story. These are accompanied by a wide range of other “blurrings,” challenging even the attempt to document them comprehensively. Much has been written about some of these blurred distinctions. Is the protest “political” or “apolitical”? Is it “authentic” or “inauthentic”? Does it represent “the haves” or “the have-nots”? Is it “Zionist” or “anti-Zionist”? Does it have a “leadership” or not? Does it have specific “demands” or is it representative of general, amorphous discontent? Can it “succeed” or not? Less has been written about some other blurred distinctions, although they are no less important. One of the most interesting of these is the blurring of the distinction between the “historical” and the “everyday.” The protesters constantly talk about their place in “history,” yet this place is constructed out of the most commonplace everyday practices. Thus, for example, the site where Israel’s Declaration of Independence was originally read and signed, on 12 Rothschild Boulevard, was expropriated from the historic “leader,” David Ben-Gurion, and transferred to the hands of “the people” – with several hundred of them re-reading the Declaration in unison and intentionally emphasizing those sentences we too often forget in the original Declaration.

4. Attempts at blurring gender distinctions have also remained largely unaddressed, apart from the common reference to the fact that many of the struggle’s “leaders” are women. The blurring of gender distinctions finds its expression, for example, in linguistic constructions straddling the line between the serious and the ridiculous. The website Shakoof Baohel (“Transparency in the tent”), which coordinates much of the struggle on the internet, defines itself as “a dream and initiative of anashot,” a Hebrew neologism that is then explained: “anashot = anashim (men) + nashim (women).” This is of course similar to the variant feminist spellings of words such as “women” (womyn, wimmin, etc.) in gender-neutral attempts in English. The site explicitly states that this alternative spelling is “an upgrading of the Hebrew language, a liberation from the chains of gender.” Official memos sent to the media likewise employ newly created suffixes to Hebrew nouns and verbs melding masculine and feminine formations and designed to simultaneously reveal language’s gender bias and reconstruct it in progressive form [e.g., meviimot is a blend of meviim (“bringing,” masculine) and meviot (“bringing,” feminine)]. Interestingly, there is relatively little linguistic consistency in these reconstructions; sometimes the masculine suffix precedes the feminine suffix, and sometimes the opposite is true. It is as though the protesters are challenging not only language’s gender bias, but its demand for systematic regularity as well.

5. Yet another distinction challenged is that between talk and action. For years we have widely accepted the distinction between those who “do” and those who “talk,” those who are active in politics and change “reality” and those who only “criticize” and “write.” Here, suddenly, we have an act that is, on the one hand, completely physical; one that involves the anachronistic placing of the human body in real physical space – not imagined space, not virtual space (one of the most picturesque placards on Rothschild Boulevard reads “The revolution will not be facebooked!”). Yet, on the other hand, as soon as all these bodies are congregated, what do they do? They talk and listen to one another! In fact, not only do they talk and listen, but they spend a significant amount of their time meta-talking, utterly fascinated by the fact that people are talking and listening to one another. “A friend of mine dragged me here despite of all the sweat,” said one attendee of a tent camp meeting. “What happened was that I sat in a conversation circle, and I realized that something different was going on here. I hadn’t seen Israeli people listening to one another like this in my entire life. This thing is crazy. What’s important is not the content, but that people are talking. Wow! It’s the first time in my life that I’ve seen people talking.” Similar statements can be heard around the tents all the time. In a space founded upon physical presence, the most important act is talk – and not simply talk, but deliberative, argumentative-yet-open-minded talk. Its final goal might be action (and it might not be that), but its primary importance is simply its existence.

6. It is these blurred distinctions that have made the struggle resonate so loudly: because it does not follow the rules we are familiar with from the field of political struggles; because it operates within a liminal space found in the cracks and fissures between categories and not within the categories themselves. The British anthropologist Victor Turner wrote about the power that such liminal spaces possess, the dangers they pose for the dominant social structure, as well as the opportunities they open up for anti-structural social change. Social dramas such as that taking place in the streets today may lead to the formation of what Turner referred to as communitas – a strong sense of community spirit in which people experience solidarity and equality, which they may then channel toward the achievement of large scale social changes. As these changes obviously pose a threat to the prevailing order, the prime goal of those who represent this order and believe in it is to terminate the blurring of distinctions, to once more force upon discourse the categories that have been blurred and lost some of their organizing power.

7. This is how the actions of social actors in fields related to the protest should be interpreted. Much has been said about the fact that the media and many members of the upper classes have been sympathetic to the protesters despite the fact that their demands are seemingly not aligned with upper class and corporate media interests. This misses the point, however. Indeed, most media outlets have been supportive of the protest, and even among the higher echelons of government there has been some support. But this support has been expressed in an ongoing, vigorous attempt to discipline the struggle, to force order upon it, to confine it to commonplace discursive categories. This is not the result of a conspiracy or bad intentions; it is mostly an expression of the institutional need to organize reality in familiar ways. This is what leads to the recurrent questions directed at the protest “leaders,” as well as to the obsessive need to identify such “leaders” (I have unsystematically counted some thirty different people who have been labeled as such by the media): “What do you want?” “What are your demands?” “What solutions do you have?” The confusion and bewilderment with which these questions are asked – and responded to – are an expression of the gap between the longing for blurred distinctions and the longing for order.

8. It is important to recognize that these two different longings do not correspond perfectly with any two sides in the struggle. The longing for blurring is more dominant among those who take part in the struggle, and the longing for order is more dominant among those who are members of the central political and media institutions. But both longings co-inhabit the mindsets of both “sides.” The lack of stable categories is thus also characteristic of the seemingly different “sides” themselves. This is true both in the sense that among protesters, some prefer clear organizing narratives to more amorphous protest, and in the sense that both types of discourses – the “orderly” and the “blurry” – simultaneously occupy the consciousness of individuals, who navigate between them constantly, not only as a result of external pressure but due to their own internal dilemmatic thinking. Viewed this way, the struggle is no less internal than it is external. Illustrating this tension is the following interview with Daphne Leef in the financial newspaper The Marker, in which she is shown reading Michel Foucault’s The Order of Things. At first glance, this would seem to be banal, shallow symbolism indicating Leef’s cool, subversive up-to-dateness. Upon second glance, however, the symbolism reveals much more. The Order of Things addresses the ways in which knowledge is categorized in discourse. It challenges the view of these categorizations as being inherently and permanently truthful. At the same time, can one subvert the hegemonic construction of knowledge in a more orderly, taken for granted, predictable way than by reading Foucault’s take on it?

9. Due to this internal and external duality, the current struggle is no less terrifying for those taking part in it than for those who oppose it. The lessons of history are also relevant here: too many good intentions have ended up disastrously for any responsible person not to be fearful of this possibility. Anyone who saw the protest “leaders” during Saturday’s demonstration saw in their eyes not only joy, astonishment, and sensory overload, but also some level of fear when confronted directly with the monster they had created. This is simultaneously the fear of their dreams being shattered and the fear of these same dreams being fulfilled in unpredictable ways. This is the fear of the moment all this will come to an end. And then, what will we have left?

10. Space, language, time: all of these partially dissolve; but they do not disappear. They remain in flux, neither completely stable nor completely fluid. Along with these, other markers of status and class are blurred in ways that simultaneously erase and preserve them: “I am equal to you” – proclaim signs in the tent camp, alongside the names of various tycoons, thus revealing how much the speaker is in fact unequal to those referenced (no tycoon, one presumes, would feel the need to publicly declare equality with anyone else). Such fluid, unstable hierarchical structures are a central characteristic of the protest. It is unclear who leads and who is led, and all attempts made by the media to identify permanent leaders and hierarchies fail time and again. It is seemingly every day that the media expose the frictions ripping apart the protest “leadership,” as well as the ongoing battles of ego and prestige at the “top”; yet virtually nothing changes in practice.

11. The same is true for physical territory: side by side in the tent camp one can find citizens protesting against very different issues, yet at the same time forming a fluid, decentralized coalition of networks with varying relations of inclusion and exclusion. Some protesters are not fond of this; some would prefer a more coherent protest orientation, clearer rules of belonging, clearly defined demarcations of what is important and what is marginal. This occasionally leads to temporary moments of unification, usually accomplished through the marking off of convenient, relatively consensual scapegoats: the ultra-Orthodox, settlers in the Occupied Territories, draft dodgers; sometimes it is based upon stronger ideological grounds. But to this date, these moments vanish as soon as they appear. The imagined “body” of the struggle operates as a rhizome, to use Gilles Deleuze’s and Felix Guattari’s conceptualization. A rhizome has no linear structure or clearly defined entry and exit points, no center and edges, and no obvious internal hierarchy. Instead, it possesses a multitude of entry and exit points as well as flexible discursive categories that enable different participants to grab on to different “handles” and identify with them. This is part of the struggle’s beauty; it is also what is so terrifying about it.

12. Recognizing this unusual structure does not require us to see all agendas as equal or to consider them similarly virtuous. But it does force us to acknowledge the human diversity constitutive of society and to deal, at the very least at the level of deliberative discourse, with the fact that different people consider different things to be important. One does not have to accept the views of those who complain about discrimination of divorced men to recognize that their protest is driven by a real sense of suffering. One may, even must, laugh at the tent protesting local beer prices – that, after all, is the protester’s intent – and at the same time identify ourselves within it, prone as we are to become more annoyed when confronted with the petty inconsequentialities of everyday life than we are angered by larger social wrongs.

13. Recently, part of the attempt to restore order to the struggle has found its expression in the demarcation of certain camp spaces as “more” or “less” authentic. The Rothschild camp – the largest and most central – has been viewed by many as being the least authentic of all, a Disneyfied circus that is inclusive of all and thus blurs the distinction between that which is important and that which is not. But the Rothschild camp, precisely because of its diversity, precisely because of its intensified playfulness, and in light of the spatial and cultural contexts in which it is situated, is in fact the most fascinating of all sites associated with this struggle. It is the site where the most significant blurrings of distinctions are made, and these challenge not only the political field (viewed narrowly), but all of our basic meaning making mechanisms. It is an explicitly carnivalesque site that celebrates, in extreme fashion, the lack of order that other sites have yet to embrace fully. It is a carnival in which “the body remembers that it is not a detached, atomized being, as it allows its erotic impulse to jump from body to body, sound to sound, mask to mask, to swirl across the streets, filling every nook and cranny, every fold of flesh. During carnival the body with its pleasures and desires, can be found everywhere, luxuriating in its freedom and inverting the everyday” – this description is taken from the definitive account of the anti-globalization movement, Notes from Nowehere – a movement that the current struggle largely resembles. It is a site that recognizes the fact that the sublime and the ridiculous have always been close neighbors, and that any attempt to separate them will inevitably miss something. This is not to say, of course, that all other tent camps, all other more specific struggles, are unimportant. Every one of them is important in its own way. But the parallel existence of all of them, and the complex negotiation they carry out with the extreme, parodying space at the center of Tel Aviv, are what invests them with additional power.

14. Within all this blurring frenzy, it must be admitted that one category remains remarkably stable – the category of the nation-state, which contains the struggle and delimits its borders. The struggle is obviously influenced to some degree by discourses emanating from outside these borders – it is rendered meaningful through its intertextual association with the recent revolutions in the Arab world and the protests in Spain, as well as the long history of non-violent struggle around the world – but it appears that it is nevertheless mostly limited to addressing civil, political, and social rights within the borders of the nation-state, as indicated by the widespread use of national symbols such as the flag. This is an unfortunate lacuna, for if there is a category that deserves rethinking and blurring, at the very least rhetorically, it is that of the nation-state. The time has come to say that the right to a life worth living should not be restricted to those who have been lucky enough to be born under the dominion of a specific flag. The time has come to recognize our shared responsibility for the lives of others influenced by our actions. This is true, of course, for those territories that are in our close proximity, and it is also true for wider contexts. The process of cross-sectional solidarity-building that the current struggle has been leading has thus far avoided any significant move toward the transnational context. Solidarity is conceptualized as solidarity of “the people,” even if – importantly – this “people” may be more inclusive than it normally is in Israel. The Occupied Territories are raised in discourse only from extremely narrow perspectives addressing the financial allocation of resources and the influence of funds being diverted to the settlements on the distribution of resources within Israel; as though public debate concerning the settlements were merely a matter of economics and distribution of funds; as though public debate should focus on the question of the settlers’ right to receive security, education, and welfare, rather than on fundamental moral issues concerning the loss of basic rights to others as a result of this right as currently practiced.

15. In the wider arena, the struggle appears to draw much of its inspiration from the transnational anti-globalization movement; yet its own borders are for the most part limited to intra-national space. It is difficult not to feel a pinch of shame every evening when the cleaning staff sent to the Rothschild tent camp – mostly comprised of African economic refugees – remains largely invisible to most of the locals and passersby. There are of course exceptions to this rule. There are those who courageously attempt to radicalize discourse from within, to connect the dots linking all different forms of abuse and wrongdoings that people are protesting against. But nevertheless, it appears that the commonsensical acceptance of the national realm as the lone site of struggle is not merely a strategic choice meant to help achieve intra-community solidarity, but also a blind spot in our collective consciousness.

16. Not recognizing the universal nature of the struggle is unfortunate, as it prevents us from seeing the connection between this local struggle and other larger scale struggles, and does not enable us to learn from others’ experiences. See, for example, the following excerpt from James C. Scott’s Weapons of the Weak, an ethnographic account of a small peasant village in 1970s Malaysia. It is not difficult to notice how similar this description is to the local struggle, at least at its outset:

The proposition that it is becoming harder and harder to find paddy land to rent is universally accepted in Sedaka [the village] and just as universally deplored. Old villagers can still recall when the father of Ghani Lebai Mat [a local villager] and a few others bought land in 20- and 30-relong [an area measurement unit] lots from Tengku Jiwa for a nominal sum. Middle-aged peasants can recall a time, not long ago, when no one in the village was without land to farm, whether as a tenant or an owner. “Then,” Abdul Rahman adds, “rents were figured with compassion, the land was cheap, and there was a lot of it; a rich man couldn’t farm more than 20 relong at most by himself.” This phenomenon of “the good old days” is, of course, socially created for the explicit purpose of comparison with the current situation. “Now,” says Abdul Rahman, completing the contrast, “one man can farm 50 or even 100 relong himself; he keeps all the money and he keeps all the rice.” Tok Mahmud’s comparison is different but complementary: “Now there are more people, rents are high, and landlords are using leasehold tenancy.”

******************

17. So how will all this end? That depends, of course, on the level of resolution used. If the expectation is for the establishment of a fundamentally new social order, here and now, then one is bound to be disappointed. The prevailing order is still strong enough, and still entrenched deeply enough in the consciousness of each and every one of us, to find ways to endure, even if at the cost of making certain symbolic concessions. Our natural tendency is still to conceptualize reality as consisting of “problems” that we need to find “solutions” for – a social construction that suggests, as Norman Fairclough elucidates, that such “solutions” indeed exist and have simply not been implemented yet. Such a view ignores the fact that there are “problems” – social wrongs, to use Fairclough’s terminology – that are not an unfortunate byproduct of the existing social order but its inevitable outcome, and as such cannot be “solved” within the prevailing conceptual system. The significance of the present struggle, beyond certain minor achievements that may be realized, and apart from the boost it has provided to our democratic and civil imagination and sense of creativity, is in the long term implications of the attempt to blur distinctions for our thinking and consciousness. These implications cannot be measured through the logic of neoliberal discourse, in which everything is quantifiable and everything can be classified as a “success” or “failure.” But if we allow ourselves to briefly step outside the borders of this dominant discourse, we will see these implications in all their blazing clarity, even if shortly thereafter we will no longer be certain whether we really saw them or not.

This article was first published in Hebrew. Click here to read the original.