Ten years after covering Israel’s Gaza Disengagement from both the Israeli and Palestinian sides, Lisa Goldman recalls four scenes that tell four very different stories and perspectives of those final weeks in Gaza.

Exactly 10 years ago, Israel withdrew its troops and settlements from Gaza in an event that was officially called the disengagement. It was a hugely controversial decision on the part of then prime minister Ariel Sharon, who rammed the proposal through the Knesset. The godfather of the settlement movement had betrayed the settlers, and they were outraged.

The local media led with the disengagement story for months, heading into saturation coverage as the August deadline approached. Television news magazine programs hosted pro and anti disengagement people in panel discussions, journalists interviewed angry settler youth who spoke about their disillusionment with the state, and overwrought analysts predicted that we were heading toward civil war.

The government had given the 7,500 settlers who lived in the cluster of Gaza communities, known collectively as Gush Katif, two options: leave voluntarily and receive a compensation package; or be forcibly evicted by the army. A few chose to leave, but the majority refused. Opposition to the disengagement became a political movement. Its adherents chose orange as their signature color, wearing orange T-shirts and orange head coverings (yarmulkes for the men and crocheted caps for the women). Orange ribbons were everywhere — outside of Tel Aviv, that is — and especially in Jerusalem and the settlements. Drivers tied them to their side view mirrors. At traffic intersections, national religious teens with orange ribbons wrapped around their wrists distributed bumper stickers with slogans like “Jews don’t evict Jews!” Supporters of the disengagement tied blue ribbons to their side view mirrors, but were otherwise quiet.

As the anti-disengagement movement became ever more vocal and organized, some of those overwrought analysts predicted that soldiers from settlements would desert rather than carry out orders to evict their fellow settlers; or that the Gush Katif settlers would attack the soldiers when they came to escort them from their homes; and that this would lead to a civil war. Hundreds of reporters flew in from all over the world to cover the overhyped event, which turned out to be pretty anti climactic. In the end the settlers were removed without violence, and in only five days.

Talking to Palestinians and Jews in Gaza

I spent quite a bit of time in Gaza leading up to the disengagement, talking to settlers and to Palestinians, and then I went back, along with a massive scrum of reporters from all over the world, to cover the event itself. The story was incredibly interesting and complex. And it left lasting impressions.

On the Palestinian side, security officials in Gaza City, wearing military berets and uniforms decorated with pins and ribbons, complained bitterly that the Israelis had refused to share information and coordinate the disengagement with them. Mere weeks before the date the withdrawal was supposed to begin, the IDF had not told them the order in which the settlements would be evacuated. “How am I supposed to ensure security if I don’t know where to deploy my men?” asked one security officer. Trust between the two sides was clearly non-existent. Israeli officials treated their Palestinian counterparts dismissively and the Palestinians tried to pretend they were not deeply insulted. Making an effort to put a good face on things, they took us to watch security forces on training exercises, preparing to replace the Israeli army in enforcing law and order. In the end there was some coordination between the IDF and the Palestinian forces, but only at the very last minute.

For an interview at the Beach Hotel Jibril Rajoub, the ousted head of the Palestinian Preventative Security Force, entered the dining room accompanied by gun toting body guards wearing sunglasses propped on their heads. He seemed to enjoy affecting a Tony Soprano persona, glaring at his interlocutor and casually using Hebrew expressions like “don’t fuck with my brain” in response to questions that he deemed “stupid.” Asked about his vision for the future of Gaza he answered in his gravelly voiced, perfectly idiomatic Hebrew, that Gaza would be the “Singapore of the Middle East” within 10 years.

Among ordinary Palestinians in Gaza, I had some touching encounters. Two men in their forties who had worked most of their lives as casual laborers in Israel, before the wall and the checkpoints went up and permits to enter became almost impossible to obtain, sat with me and answered my questions in fluent Hebrew. One asked me if I knew “Avi, who owns the event hall in Petah Tikvah.” No? “Years, I worked for him.” They were glad the army and the settlers were leaving, they said, but afraid, too. They didn’t trust Mohammed Dahlan, Fatah’s strong man in Gaza, to administer the place. And they didn’t like Hamas either. Nor did they trust the Israelis. “Israel could just lock us in here and throw away the key,” observed the one who had worked for Avi in Petah Tikvah. His friend nodded. “And Gaza would become a big prison.”

As I got up to leave I asked if I could take their photos and they assented, smiling tenatively into the camera lens. But as I walked away they must have had second thoughts because they chased me down the road, calling me. “Don’t use our names,” they said. “It could be dangerous.”

As for the settlers, they seemed to have many reasons for not wanting to leave. Many of of them lived in communities that resembled a suburb in southern California. Their homes were spacious and well appointed, surrounded by lush lawns and shaded palm trees. Theirs was a lifestyle that very few people living inside Israel proper could afford.

For some, the objection to resettlement was primarily financial. Prosperous farmers said the government was not offering them sufficient compensation for the businesses they had built from scratch, growing fruits and vegetables for export. But a significant factor underpinning their wealth was cheap, non-unionized Palestinian labor to harvest, sort and pack their crops. Even if the money they received from the government were enough to rebuild their farms inside Israel, they would have to pay much more for labor.

People who worked in underpaid professions like teaching, architecture and nursing objected to giving up their quality of life as well. They could afford three-bedroom bungalows with tattered little back yards in Gush Katif, which functioned as a bedroom community for jobs in nearby Ashkelon. Inside Israel their salaries would afford them only a small apartment in a down-at-the-heels inner city neighborhood . But the same architect who complained bitterly about being forced to give up his modest bungalow with the attached covered carport also pointed at a dent in his calf and said it had been caused by shrapnel from a Palestinian rocket shot at his settlement. “We have sacrificed for Israel’s security,” he said. Then he added that if I really wanted to feel how wonderful it was to live in Gush Katif, I should come spend a Shabbat with his family. “The sense of spirituality and community are irreplaceable,” he said, adding that children wandered freely in the community and everyone left their doors unlocked. From the material to the nationalist to the spiritual, there were many reasons to resist being displaced from one’s home. Not all the settlers were religious — a handful of them seemed to be totally apolitical beach bums who spent their days surfing — but even those who were did not offer the Hebrew bible as a reason for maintaining control of the territory. Unlike the West Bank, where so much of the action in the Old Testament takes place, Gaza is infrequently mentioned and was not the site of any significant events.

A Woodstock moment for ‘national religious’ youth

But for the religious settlers, giving up territory was a sin. An old friend, who was not a settler but was politically aligned with the national religious movement, told me that the rabbis at her teenage sons’ schools were inciting their pupils against the government and encouraging them to break the law by sneaking into Gaza, after the army closed it to non-residents, in order to stage political protests. She used the terms “whipping them up” to describe the rabbis and youth group leaders’ lectures to the young people, and said the teenagers had been “brainwashed.” My friend was upset about this, but felt she had lost her ability to influence her children on this matter. Everyone at her synagogue and in her tight-knit community was vociferously opposed to the disengagement and open dissent would have come at the price of social ostracism.

Later, I met some of those ideological teens in Gaza. They were very volatile.

The deadline for the disengagement arrived and the vast majority of the settlers were still in Gaza, giving no indication of any intention to leave. The journalists who had not embedded in the settlements gathered at the media center near Ashkelon, and during the pre-dawn hours were driven in to the territory on chartered buses, accompanied by soldiers. And then we spent a lot of time standing around in the killingly oppressive August heat, with its high humidity and relentless sun, waiting as soldiers gently cajoled families to leave their homes. It took hours and hours. We had to drink water constantly, because of the heat and the lack of shade. But there were no public toilets and no shrubbery to hide behind, which for the female reporters was an ongoing problem.

Some of the national religious teens who had snuck into Gaza seemed to be having a Woodstock moment. When we arrived at dawn on the first day a group of boys was standing outside barefoot, wearing short pants and oversized orange T-shirts, praying the morning service with audible passion. Some were sitting on low bungalow roofs, shouting insults at the reporters and smoking what smelled very much like hashish. “Egyptian hashish,” snorted an Israeli colleague. Groups of teenage girls wearing long, peasant-style skirts and oversized orange T-shirts swayed back and forth, one arm wrapped protectively around their abdomen and the other clutching a prayer book, their eyes closed and lips moving silently as tears ran down their faces.

Days of evacuation

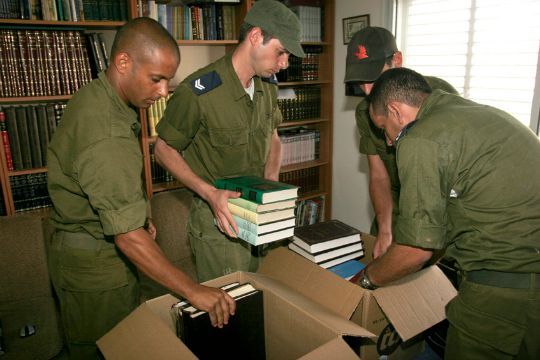

Since the settlers had said they would not leave, they also had not packed up their belongings. So the sequence of events, which became well established within a day, went like this: first the soldiers entered the settlement in formation, wearing their specially designed uniform vests and matching baseball caps emblazoned with telegenic Stars of David.

As they entered each settlement, they were met by choruses of abuse from the residents. In a settlement called Kfar Darom, adolescent anti-disengagement activists barricaded themselves on the roof of the synagogue, from which they pelted the soldiers with buckets of paint, rotten fruit, eggs and who knows what else. Remarkably well trained for this mission, the soldiers never lost control of their emotions and never objected to being cursed, yelled at or spat upon. Given the explosions of rage I’d seen soldiers direct at Palestinians in the West Bank, this restraint was not only admirable but also remarkable.

In small groups the soldiers approached pre-assigned homes, knocked and politely asked permission to enter. Then they sat down and spoke gently with the family, listening patiently and sympathetically to their recriminations and angry words. Sometimes they joined them in prayer at the synagogue. In at least one case, the officer who sat and listened empathetically to an angry family introduced himself as Sharif. He was a Druze. Usually, the residents of a given home were convinced to leave, escorted to buses and transported to hotels inside Israel, pending a permanent relocation. Sometimes soldiers would physically carry angry teenagers to the buses. Then more soldiers entered the empty homes to pack up the families’ possessions, which would be delivered to their new homes. A great deal of media attention was paid to the emotional state of the soldiers, who were supposed to be terribly upset about having to evict fellow Jews from their homes. But mostly they were just very tired. They were up before dawn every day, outside in the August sun all day long, and it was far, far too hot to expend so much physical and emotional energy.

The settlers had clearly memorized certain talking points. Sometimes they appealed to the soldiers for solidarity, stressing their tribal commonalities and even hugging them or crying with them. But mostly they were enraged and completely unable to control what came out of their mouths. After listening three or four times to sobbing teenagers and to young mothers clutching their babies as they screamed at soldiers that they should be ashamed to evict Jews from their homes, that they were Nazis and traitors and how could they live with themselves, the scenes just blurred together and the sense of authenticity was lost. And after watching a bearded father turn red as he yelled that he had served years in an elite combat unit, had devoted his life to the land of Israel and look how it had betrayed him, and why don’t you immoral leftists just go back to Tel Aviv and dance in your discotheques … Well, compassion fatigue sets in pretty quickly. Especially when these same people who were demanding sympathy for their plight expressed rabidly racist sentiments about Palestinians specifically and Arabs in general — to my face, in response to very anodyne questions about the people who lived in the low-rise apartment blocks just a few minutes’ walk away.

On the very last day of the settler evacuation, at a settlement called Netzarim, I met a soldier who said he’d served his annual reserve duty there. He told me resentfully that 350 soldiers had guarded the 65 families on that settlement, year round, but I never checked the number and have no idea if it was true. He stood in front of the sign leading into the settlement, smiled and asked me to take his photo. He was happy that he would no longer have to spend one month each year guarding a settlement in Gaza.

The leaders of Netzarim had worked out an agreement with the army. They would not fight evacuation, as long as they were allowed to have a farewell morning prayer service at the synagogue. Despite this promise, when we arrived at dawn the residents of the settlement were still behaving as though there was going to be a divine intervention. A woman was hanging out laundry, children were riding their bicycles, and a group of teenagers were pouring cement onto the foundation of a new house. In answer to my question, one boy mumbled something about it being a sin to stop building the land of Israel. Then, in an abrupt and violent gesture, he thrust the dirty metal bucket toward my face, almost hitting my nose, yelled an insult at me and walked away. But unlike in the other settlements, there were no rows of abusive residents screaming at the soldiers who had come to take them away. Children milled about quietly outside the synagogue, watched over by female soldiers acting as babysitters, while the adults prayed inside.

While the morning prayer service continued for what seemed like a very long time in the large, domed synagogue that dominated the tiny settlement, I sat under a tree with some friends, waiting for the next stage. Dying for a toilet and chagrined to see that there was, once again, nowhere to go, I tried to think about something besides my full bladder and my thirst, which I was afraid to quench. Suddenly, from the window of the house right behind us, we heard a group of female voices shrieking so loudly and desperately that we all sat up and looked at one another. The screams turned out to be coming from three teenage girls, all wearing identical orange T-shirts with slogans that read “Netzarim forever.” They were sitting on a couch with their arms wrapped around one another, red faced, sobbing to the point of hyperventilating, and refusing to be moved. Their gut-churning shrieks reminded me of the courtroom scene in “The Crucible.”

Outside, the rabbi of the community was being led slowly from the synagogue to the bus, physically supported on either side by uniformed soldiers. Behind him, a long procession of Netzarim residents walked slowly into their exile. Soon the shrieking girls, now a bit calmer, joined them and climbed onto the bus. And that was it. By lunchtime, the settlement was a ghost town. I sneaked into one of the vacated homes to use the washroom, which smelled as though someone had just finished taking a shower with a popular local brand of soap. There was a half used roll of pink toilet paper on the cylinder next to the sink.

And then it was over

Three weeks later, I stood on the roof of a Palestinian apartment building that overlooked Netzarim. A couple of guys from the north of Israel, Palestinian citizens who worked as reporters and cameramen for Arab satellite channels, were filming the dismantling of the settlement. As per agreement with the Palestinian Authority, Israel had taken responsibility for destroying the buildings before handing the property over to the locals. But instead of using the massive Caterpillar D9s that the army generally employed to bulldoze Palestinian property, they were using a tiny tractor that looked like something a landscaper would use for a large garden. It seemed to be moving slowly in circles, and half the houses in the little settlement were still intact.

We sat under the tarp the guys had erected for shade, chatting and watching and drinking coffee they brewed on a primus stove. I remarked that it was slow going, this settlement dismantling business. One of the guys snorted and gestured to three enormous piles of rubble on the other side of the building we stood on, in the Palestinian area. “See those?” he asked rhetorically. “They were homes for nine families. Took 20 minutes to destroy.”

Later, I heard that most of the residents of Netzarim had moved to Ariel, on the West Bank.