The story of Jacob Israël de Haan, a Dutch author who was killed by Jews in Mandate Palestine for his anti-Zionist views, could teach Israelis an important lesson about tolerance, one that is not lost on those who remember him in Amsterdam.

By Ido Liven

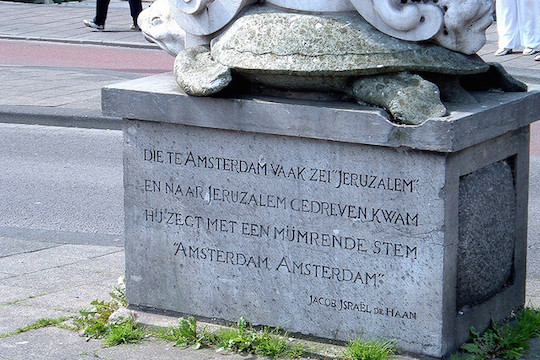

One stone pillar standing in central Amsterdam is anything but a tourist attraction, certainly nothing like the Rembrandt House Museum just across the street. Rather, it is a memorial dedicated to Jacob Israël de Haan, who was murdered 90 years ago today.

I used to go past it almost daily when I was living in the city but it was a story I wrote about a neighborhood in a different part of Amsterdam that introduced me to de Haan.

I couldn’t help trying to situate this truly outstanding character from the early 20th century in today’s Israel. Things have changed dramatically in the nine decades since his death, but de Haan’s story offers a vivid illustration of how far modern day Israeli society still is from the inclusive character it so desperately needs.

Here’s a brief overview: De Haan was born to a Jewish family in the north of the Netherlands and worked as a journalist in Amsterdam. As an author he is probably best known for his book, Lines from De Pijp (“Pijpelijntjes”), which takes place in an Amsterdam neighborhood of the same name. Considered the first Dutch homo-erotic novel, the book managed to stir quite a controversy at the time, leading some to believe the protagonists mirror De Haan and his friend, Arnold Aletrino, to whom the books was originally dedicated.

A secular homosexual author who received a PhD in law at the age of 28, de Haan married a Christian woman who was a few years older than him. Later, however, he became ultra-Orthodox and immigrated to Palestine as a devout Zionist.

Several years after that de Haan had a change of heart, and he engaged in the opposition to the Zionist enterprise. On June 30, 1924, he became the victim of what Wikipedia now refers to as, “the first political murder in the Jewish community in Palestine.”

To some, De Haan’s persona might fit in the eclectic image of the Dutch capital – a city that’s also commonly nicknamed ‘Mokum’, from Yiddish for ‘place.’

To be sure, despite its uber-liberal reputation, xenophobia is disturbingly prevalent among contemporary Dutch society. And yet, in 2001 it was The Netherlands that became the world’s first nation to legalize same-sex marriage. In fact, in January 2012, Amsterdam’s Jewish community suspended its chief rabbi after he had written that homosexuality is an incurable disease.

Also, mixed couples – married or not – are also a non-issue in The Netherlands.

In Israel none of that is possible. Sadly, in a society that sees itself as open and liberal, both same-sex and inter-religious (or simply civil) marriage are considered a red rag. In fact, had he lived today, De Haan would probably have been as much of an outcast today as he was before being assassinated in 1924. At best he would be cast by the producers of “Big Brother” (a TV format ironically – or not – created by the Dutch production company Endemol.)

Comfortably ignoring these aspects in his story, the anti-Zionist Haredi sect of Neturei Karta have since embraced De Haan as ‘Professor Saint.’

And it seems that the lesson has not been learned. One does not need to endorse De Haan’s political agenda to recognize the possible ramifications of intolerance toward another’s political convictions.

Consequently, while viewed as a respected author in The Netherlands – whose government today is one of Israel’s most ardent European supporters – De Haan’s story largely remains a blind spot in the Israeli narrative.

The modest monument dedicated to him, located at what used to be Amsterdam’s Jewish quarter, bears a quote from one of his poems that was published the same year he was assassinated:

Who in Amsterdam often said ‘Jerusalem’

And finds himself driven to Jerusalem

Whispers in a wistful voice

‘Amsterdam, Amsterdam’

Ido Liven is an independent journalist covering mainly environmental issues and foreign affairs for Israeli and international publications. A version of this post first appeared on his blog.