Israeli leaders and advocacy groups love to complain about Palestinian incitement, but militaristic and nationalistic indoctrination is all too common in Israel itself. Some personal reflection, following a mail from an outraged parent

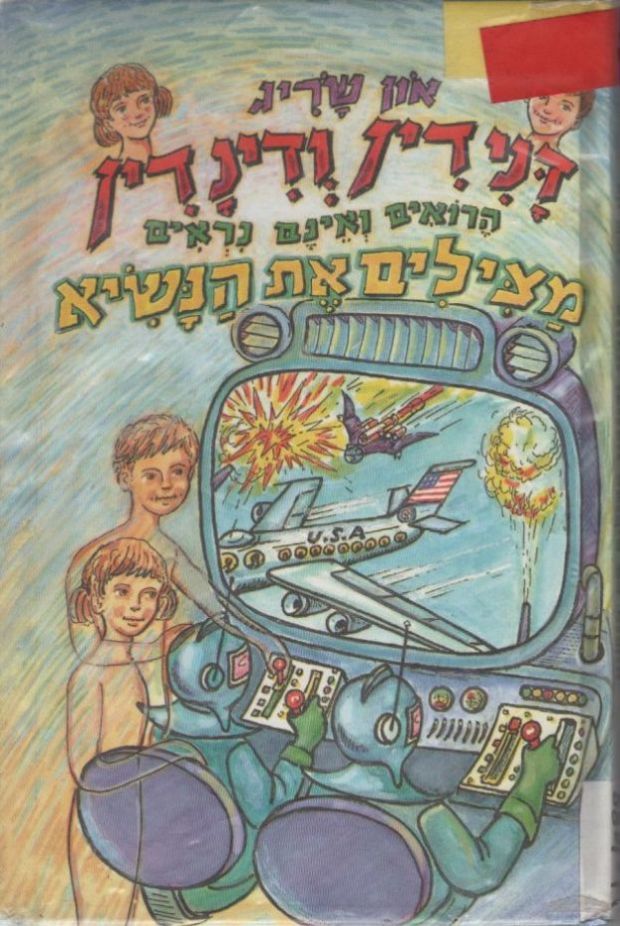

When I was a kid, I loved Danni Din stories. Their hero was wonder-kid Danni Din, which became the worlds’ only invisible person after mistakenly drinking a strange liquid left on the window by the reckless Prof. Katros. As befits superheroes of his kind, Danni didn’t take advantage of his unique condition by rushing into the girl’s dorms, but instead dedicated his childhood to helping Israel’s security forces. Danni Din fought in the Six days war, caught terrorists and rescued IDF prisoners, and though even at a very young age I sensed there was something tragic in his condition (he was to remain invisible forever, not to mention the fact that he never seemed to grow up), I dreamed of getting the opportunity to perform such heroic acts for our country myself.

Last week, in the wake of another round of the endless debates over the “Palestinian incitement”, I got an e-mail with pictures of the front and back cover of one of the latest Danni Din stories, published in 1997. The author of the mail, an Israeli parent, was shocked to see the militaristic tone in the book his son, a second grader and an avid reader, brought home from the public library one day.

“Saving the president”, the 1997 Danni Din story, featured a new heroine: Dina Din, the invisible girl. The book has a somewhat bizarre plot: the invisible kids are abducted by extraterrestrials (the late 90’s were the days of the X-Files mania), only to escape after a fierce battle, in which they take control over the aliens’ spaceship. Headed back to earth, they intercept a plot by Hamas to send a flying suicide bomber that would crash into president Bill Clinton’s Air Force One – on his way to Israel, naturally – with the intention of blowing up the plane and killing all its passengers.

“Will our invisible heroes succeed in saving the beloved president and the planes passengers from death?” asks the back cover.

Danni Din’s war on Arab terrorists is not unique. Almost every adventure book I remember from my childhood featured at least a handful of evil Arabs (never mention the P word), if not full Egyptian military divisions. Some of the Arabs in those books were thieves and kidnappers, but most of them were terrorists.

The best known of these books were the “Hassamba” series, featuring a group or kids operating like a secret army unit in the service of Israel’s defense, getting their orders directly from the most senior generals. These books weren’t about politics: While Shraga Gafni, the author of Danni Din series (as well as many other Israeli classics), was a rightwing ideologue , Hassamba’s Yigal Mossinson was a Tel Aviv bohemian. His books were a bit more sophisticated, but the militaristic-nationalist tone was largely the same.

Whenever I hear Israeli advocacy groups speaking of incitement, I think of Danni Din and Hassamba. I also remember the maps of Israel we use to draw in school: none of them featured the green line, just one big happy Jewish state, from the sea to the Jordan; and we never marked the Palestinian towns on them, only Jewish cities. Does this qualify as incitement?

Naturally, there are many examples of hardcore anti-Arab incitement in Israel: from streets named after the racist Rabbi Meir Kahane and Minister Rahavam Zeevi, who promoted the idea of transfer, to graffiti and even rabbinical orders calling for killing and expulsion of Palestinians. But these are the obvious cases, to which people pay attention. There is something about the “innocent” examples, like kids’ novels and pre-school work pages that show the depth of militaristic and nationalistic indoctrination in Israel. It’s almost impossible to grow up here without being told to fear and hate the Arabs, or to idolize the army.

Naturally, none of this prevents Israelis from seeing themselves as a peace-loving nation. In fact, I think that the real message of these books is that we fight the Palestinians because they prevent peace. We are forced to conquer and sometimes kill in the sake of a greater good (like saving Air Force one from a suicide attack). Isn’t that what you hear from advocacy groups like Stand With Us and The Israel Project – that fighting the Arabs alongside Israel is not just Israel’s interest, but the US’, or even the world’s?

——————

I remember watching the military parade for Israel’s 40’th anniversary. The main event took place in the National Stadium in Ramat Gan, not far away from where I grew up. I was 14, and extremely exited that my parents got us tickets for the event, even though it was the cheaper of two shows, the one in which air force didn’t take part.

Behind us in the stands was another family, with younger kids. I have a very vivid memory of a certain point in the show in which the announcer describing the army unites and armed vehicles on the field in front of us said something like “The IDF’s real battle is for peace,” and the young kid sitting behind me burst into a spontaneous laughter. It sounded very stupid to him, “fighting for peace,” and he said so to his dad. In the next few minutes, this father explained to him why this phrase actually made perfect sense. I remember being embarrassed for the kid, which clearly didn’t understand what the army was all about. Much later, I thought he was right: It was a stupid sentence.

This Israeli dialectic of militarism and peace couldn’t have been better demonstrated than in these kindergarten Independence Day assignments from 2009, sent to me together with the Danni Din cover. They made me think of the infamous “suicide baby” picture, and how it became for many the symbol of the “inhumane” Palestinian culture.

.

One final word on this: It wasn’t my intention here to deny Palestinian incitement or hate-talk, or to say that our side is worse. Political indoctrination exists on both sides. Perhaps this is the reason Netanyahu refused to renew the work of the joint Israeli-Palestinian committee against incitement – he knew that it would have its hands full with evidence from both societies.

More than anything, I think that the complaints over Palestinian incitement are excuses to avoid real political action on behalf of Israel. I actually find it hard to believe that as long as the occupation continues – and the resistance to the occupation, which is natural and justified – we will be able to rid ourselves completely from the problem of “incitement”. Only after we deal with the political issues at the heart of the conflict, we could succeed in changing our children’s books.