Since 1967, the Israeli media has hid the ugly, everyday reality in the occupied territories. But even if they really knew, would Israelis still choose to end 50 years of military rule over the Palestinians?

By Yizhar Be’er

According to the democratic-liberal-utopian model, let us assume for a moment that every citizens has access to all the information about the reality that surrounds us. In this world, Israelis would know everything about what is being done in their names in the territories occupied in 1967. And what would happen then?

Over the past few months I have been producing a radiophonic project on the first years in the Gaza Strip after 1967, as part of a series of podcasts I host on Israeli myths. I interviewed, among others, two of the military governors who oversaw Gaza in the first years of the 1970s. At that time the IDF took harsh action against Gaza, and had soldiers been caught on camera by the likes of B’Tselem (which did not exist back then), the world would have come down hard on us.

Lieutenant Col. Ini Abadi, who was then the military governor of the Gaza district, castigated me when I asked him about the army’s “policing activities” vis-a-vis the Palestinian population in the Strip. “These were not policing activities… this was terror! Israeli terror against civilians!” he nearly yelled at me, “and I was in charge of it!” How many Israeli journalists would ever dare speak this way, then and now, not to mention politicians?

Champagne in exchange for dead terrorists

There should be no doubt: Israelis should have known what kind of trouble “holding on to the territories” would bring in the first two to three years after the 1967 War. If only journalists and the local media would have delivered the proper information.

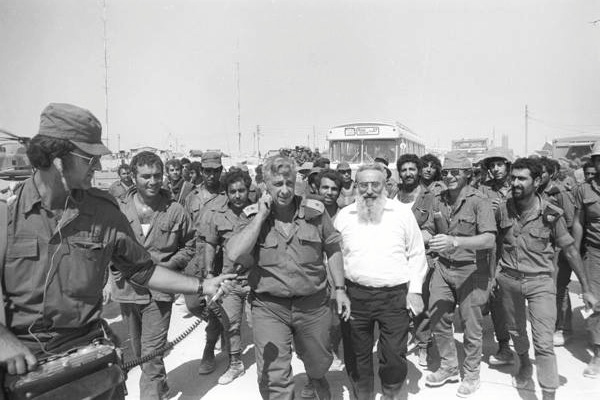

As I gathered more information for my project, I discovered terrible things — some of them yet unknown — that the IDF did in Gaza under the Ariel Sharon, who headed the Southern Command at the time. In an interview with former Major General Yitzhak Pudak, who served as the military governor of Gaza and northern Sinai at the time, he told me about a bound prisoner who was taken from his cell in Gaza so he could point out the exact spot where he had hid weapons in an orchard. After revealing the hiding spot to his interrogators, they shot and killed him. When I asked the two governors whether this was an isolated incident, they said no. There were many such cases, they responded.

In one of the intelligence reports submitted to Pundak in his capacity as military government, he read: “Our unit chased a wanted terrorist in Al-Shati refugee camp. He ran into one of the buildings. The unit captured him, disarmed him, and killed him inside the home.” Pundak described how he heard Sharon promised those under his command a bottle of champagne for every dead terrorist. Those who take a terrorist hostage only get a soft drink. Pundak, who often prevented Sharon from doing whatever he wanted, was nicknamed “the terrorist” by the latter.

In addition to extrajudicial killings, the IDF demolished thousands of homes without any reason, expelled entire populations, and collectively punished civilians. Or put otherwise: it committed war crimes that were covered up and kept secret by the defense establishment and military censor. The first silence breakers came from the Nahal Brigade, who saw others abuse men, women, and children with whips and batons, who saw soldiers loot money and property and sow destruction in Palestinians’ homes. Four Nahal soldiers, astounded from what they saw, wrote to Prime Minister Golda Meir, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan, and Haim Bar-Lev, the IDF’s chief of general staff.

On the same day the letter reached the top brass, the four soldiers were summoned for a meeting with Bar-Lev, after which it was decided to appoint an investigative officer who will look into their claims.

“This is not the hour to pat ourselves on the back,” wrote journalist and historian Amos Elon in Haaretz, all while patting himself on the back. “It seems to me that there are not many armies in the world that would respond to a similar letter of complaint so promptly and at such a high rank… The fact that it was an internal army mechanism that brought about the General Staff’s conscientiousness is noteworthy.”

When the media is silent

During IDF’s operations to “eradicate terrorism” under Ariel Sharon, Gaza was closed off to both Israeli and foreign journalists. When the Strip was re-opened, Elon visited alongside several other journalists, writing about the “grenades, atrocities, mass arrests, violent demonstrations, and beatings, rocks and curses… and whips.” He confirmed what the four Nahal soldiers had seen. “Some homes look as if they had just undergone an earthquake,” he wrote.

After the establishment of an investigative commission, Bar-Lev admitted that there were “unusual deeds,” and decided to administratively censure two officers and hold disciplinary hearings for a number of soldiers. The vast majority of Israelis believed the military governor that these were just a few rotten apples and that the occupation was nothing more than a minor distress.

Despite the fact that the Nahal soldiers’ testimonies were confirmed — and even after Elon described what he saw and heard — Haaretz’s editorial praised the IDF’s quick response, expressing hope for better days: “We must take into account that the army may, in the future, be forced to fulfill non-combat roles, but border more on policing roles… the chief of staff’s steps cleared the atmosphere. Reaching the aforementioned practical conclusions may prevent future failures.”

And what would count as a failure? Amos Elon eventually left Israel, which he termed “quasi-fascist,” after growing disappointed and despondent from the possibility that Israel would ever free itself of the curse of occupation. He died in Tuscany in 2009.

After the drums of victory of 1967 abated (although they have never truly subsided), we sat and waited for 50 years for the end of the occupation, which never arrived. In the meantime we read, heard, and watched the simple, censored story about ourselves, which we were told by the media — a story so simple. And since it is so simple, let’s summarize it in one sentence: in the ongoing, unsympathetic fight in the Middle East between the Good Guys and the Bad Guys, we will always belong to the first group. The rotten apples must be taken care of in order to prevent “future failures.”

The new silence breakers

The failure of the media to portray the full picture of the occupation and its ramifications led the creation of civil society organizations, which provided information that could not be found in the mainstream media.

B’Tselem, which was founded in 1989 during the First Intifada, would not have come into existence had the press told real story on what was happening in the occupied territories in those years. For many years, Channel 1, the only television station in Israel at the time, did not have a reporter in the West Bank or Gaza, and the main source of information on the goings on there — which did not come directly from the IDF Spokesperson — was B’Tselem.

According to the rules of the game back when I served as the executive director of B’Tselem, and to save face, the army would once or twice a year send someone on behalf of the IDF Spokesperson to check B’Tselem’s statistics. The IDF trusted the information we published over that which was published by the press — even more than the problematic statistics it itself had gathered. After the army had updated its statistics in accordance with the information it received from B’Tselem, the IDF Spokesperson would free up time to publicly attack the organization for its lack of integrity.

Breaking the Silence, which was founded in 2004, would not have come into existence had the Israeli media done its job and told the real story of what was happening in the occupied territories after the elimination of the Oslo process. Several other organizations were also founded in response to the media’s failures. But Breaking the Silence, B’Tselem, and other human rights organizations — as well as those dedicated journalists who went out to the field and sent back factual reports — were unable to change the big picture.

The information that the media and civil society organizations bring could light the way, if only the public were determined to use it for such purposes. But the Israeli public wants to read articles that align with its prejudices and fears. Thus, the thought of what could have happened to us had the media provided the public all the information on what was taking place in the new post-1967 Israeli empire — presetting it with the true economic, political, and moral costs of maintaining the burden of occupation — leaves me feeling doubtful.

“Peace comes to those who developed the ability to catch it,” says Lewis Orne, the main character of Frank Herbert’s science fiction novel, The Godmakers. Thus, one must unfortunately assume that the Middle East would not have fundamentally changed even if the media would have covered the occupied territories differently.

Surveys show that even today the majority of Israeli Jews place more trust in the IDF than any other public institution (82 percent, according to a study by the Central Bureau of Statistics). The legal system came in fourth place, while only 28.4 percent of Israeli Jews trust the media — lower than any other institution. That’s what happens when, according the Central Bureau of Statistics — 80 percent of Jews in Israel believe in God, and 67 percent think we are the chosen people. That’s what happens when approximately half of Israeli Jews want to expel Israel’s Arab citizens.

Israeli society, like other societies in violent conflict zones, is an enlisted one — so don’t bother it with complex messages. Militarism, siege mentality, viewing criticism as treason, hatred for minorities, a cult of traditionalism, exploiting social distress, and anti-intellectualism are all signs of a society that is growing more fascistic, as Elon sensed before he left for Tuscany. This kind of society develops systems of beliefs, positions, and feelings that suit the conditions of the conflict. It creates goals for the existence of the conflict and formulates justifications for them, while completely glorifying itself and presenting itself as the victim. It strips the other side of humanity and develops a motivation to fight against it. The last thing that this kind of society is interested in is more bad news that may besmirch public trust. Or as Karl Popper once described it: our knowledge can only be finite, while our ignorance must necessarily be infinite.

Yizhar Be’er was a journalist in the occupied territories, served as the executive director of B’Tselem, and is the executive director of Keshev – The Center for the Protection of Democracy in Israel. This post was originally published in Hebrew on Local Call.