Trump’s administration needs to come to terms with the unacceptability of states snatching territory from other states through armed force and keeping it — no matter what rationale the historical context might provide.

By Paul R. Pillar

The main takeaway from the recent G-7 summit obviously is the striking damage to U.S.-allied relations from Donald Trump’s posturing and accusations about trade. Also worth assessing, however, is a different and milder disagreement between the U.S. president and the other summit participants.

With support only from the Italian prime minister, the front man for a newly installed populist coalition in Rome, Trump urged that Russia be readmitted to the group. The Group of Seven was established in the 1970s and did not expand to include Russia until the 1990s, after the collapse of the USSR. The other seven members suspended Russia’s participation in response to its annexation of Crimea in 2014.

Forceful seizures of territory that have been allowed to stand despite international condemnation have been extremely rare since World War II. Seizures through armed aggression that were not allowed to stand but were instead reversed with military force have included North Korea’s invasion of South Korea in 1950 and Iraq’s swallowing of Kuwait in 1990. But although unreversed seizures are rare, Crimea is not the only one.

In June 1967, Israel initiated a war with a surprise attack on Egypt. After Egypt prevailed on Jordan and Syria to enter the war, victorious Israeli forces seized territory from all three. A later settlement negotiated with Egypt included the return of the captured Sinai. Jordan disavowed any claim to the Palestinian Arab-inhabited West Bank, which Israel continues to occupy. And in the Golan Heights, Israel continues to occupy, 51 years after its capture through armed force, a chunk of Syria.

For many years, and even after Menachem Begin imposed Israeli law on the Golan Heights in 1981, Israel in effect acknowledged that the Golan is Syrian by negotiating with Damascus over its possible return. Negotiations came closest to an agreement in 2000, with the main remaining sticking point involving ownership of a few meters of shoreline on the Sea of Galilee and whether Syria would have direct access to its water.

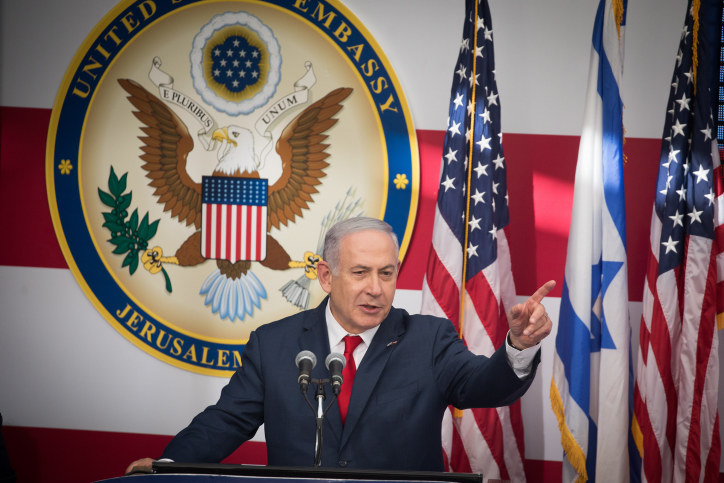

In more recent years, however, the entrenchment of the extreme right in Israeli politics and the overall hardening of Israeli policies have extended to policy toward the Golan Heights. In February of this year, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared to the United Nations secretary general that Israel will keep the Golan forever. The international community universally refuses to recognize Israeli ownership of the territory.

Any Israeli claim to the Golan Heights is weaker than the Russian claim to Crimea. The latter at least has a history of being part of the Russian Republic before Nikita Khrushchev gifted Crimea to Ukraine in the 1950s — back when Russia and Ukraine were both part of the USSR and few people elsewhere noticed or cared. Most Crimean residents are ethnic Russians, and the takeover by Russia was generally popular with them. By contrast, the story of the Israeli seizure of the Golan Heights is a simple one of brute force. The territory was never part of Israel or of Palestine. The residents (before Israel started colonizing the territory) are Syrian Druze, most of whom have refused an Israeli offer of citizenship.

Trump’s proposal to readmit Russia to the G-7, making the group once again a G-8, may have been as little thought out as many of his other moves. Reportedly officials of the National Security Council were taken by surprise. But the proposal has validity for the same reason it made sense to admit Russia in the 1990s. Russia is a major player that must be included in order for the body effectively to handle many important issues of international politics and, to a lesser extent, economics.

The other members of the G-7 need to come to terms with that consideration, given the near-zero chance that Crimea will ever again be part of Ukraine. Perhaps some formula can be devised that yields the benefits of diplomatic engagement without yielding on principle regarding military land grabs. Restoring the G-8 need not be a recognition of ownership of Crimea or the taking of a position regarding any other territorial dispute.

For its part, Trump’s administration needs to come to terms with the unacceptability of states snatching territory from other states through armed force and keeping it, no matter what rationale the historical context might provide. The case of the Golan Heights may provide a clearer test than Crimea does of the administration’s inclinations in that regard, given that it poses a simple question of recognition or nonrecognition, without any diplomatic engagement at stake.

Netanyahu’s government — feeling especially confident, after Trump’s move of the U.S. embassy to Jerusalem, about its ability to steer U.S. policy — is pressing the administration to recognize Israel’s annexation of the Golan. A Republican congressman from Florida recently introduced a proposal to that effect, but it was not brought to a vote. It is unclear whether the administration weighed in on the matter with the Republican leadership in the House of Representatives. But given the recent history with the embassy issue, it would not be surprising if Trump eventually were to bow to the Israeli government’s wishes on this issue too.

Trump doesn’t like the concept of a “rules-based international order.” The U.S. delegation at the G-7 summit reportedly objected to use of that term in the summit communiqué. Trump probably does not understand the extent to which that order, which the United States had a huge part in shaping after World War II, works to the advantage of the United States. To the extent that Trump is dwelling in the realm of slogans, which he probably is, then “rules-based international order” always will lose out to “America first” or “make America great again.” But focusing on one specific rule gets out of the realm of slogans and into well-defined norms of international behavior.

Will Trump accept that a rule against states using military force to seize pieces of another state’s territory is in U.S. interests as well as the interests of international peace and stability? If he doesn’t, why not?

Paul R. Pillar is non-resident Senior Fellow at the Center for Security Studies of Georgetown University and an Associate Fellow of the Geneva Center for Security Policy. He retired in 2005 from a 28-year career in the U.S. intelligence community. His latest book, published in 2016, is ‘Why America Misunderstands the World.’ This article was first published on Lobelog.com.