“The story of the occupation is here for everyone to see,” Dror Etkes mutters, half smiling, as we stand on a hilltop in the West Bank settlement of Haresha. “The problem is very few people are willing to see it.”

The view from Haresha, one of several settlements that comprise the “Talmonim bloc,” approximately 10 kilometers northwest of Ramallah, is spellbinding in both its beauty and scope. Looking west, the foreground is littered with rows of Jewish settlements dotting the arid hills. Beyond them is a row of Palestinian villages — Ras Karkar, Ein Ayub, and Deir Ammar — lined north to south. Even further yet another cluster of settlements hugs the Green Line, effectively cutting off any chance for Palestinian territorial contiguity here.

Talmonim is the logical conclusion of 50 years of military occupation. “This is the backyard Israeli society prefers not to talk about,” Etkes says sheepishly, as he gazes out over the sprawling settlement bloc from the vista point. “If you think Talmonim will stop expanding, you’re a fool.”

Etkes, 48, is one of Israel’s foremost experts on Israel’s land management and settlement policies in the West Bank. For the better part of the last 15 years, he has tracked how the Israeli army seizes and expropriates land, how it declares private plots “state land,” and makes illicit back room land deals.

I spent a day traversing the West Bank with Etkes in order to see, and not just hear or read, the story of how the Israeli settlement enterprise, and the occupation, became what they are today.

The story he tells is not a new one. It’s not difficult, driving through the West Bank, to notice the stark difference between Jewish settlements and the neighboring Palestinian towns and villages. And yet there is something about seeing Israel’s territorial expansion through Etkes’ eyes that puts the entire situation in a far clearer and starker light.

As he drives north on a winding road, Etkes explains that the goal of the Talmonim settlement bloc is two-fold: to increase Jewish presence in the area, breaking up territorial contiguity in what the international community considers a future Palestinian state, and to make it impossible for Palestinians to do just about anything in the West Bank without encountering the Israeli army.

‘In Israel it is very easy to become a settler’

Etkes navigates the roads of the West Bank like the back of his hand, ticking off the names of the Palestinian villages or Jewish settlements we drive by. He speaks in a gruff, sardonic tone, often providing tidbits of information on the reality on the ground before making sure, with incredulity, that I understand the absurdities of what we are seeing.

Yet despite his often brutally sarcastic tone, one thing is clear as you travel with Etkes — he believes in showing basic human solidarity with those who are afforded far fewer privileges. At one point, as he is speaking in fluent Arabic to two middle-aged Palestinian men near the Jordanian border, a police car pulls up alongside us. An officer no older than 40 is in the driver seat, next to him a young Israeli soldier. “They with you?” the officer barks. Without so much as thinking, Etkes responds: “I’m with them.”

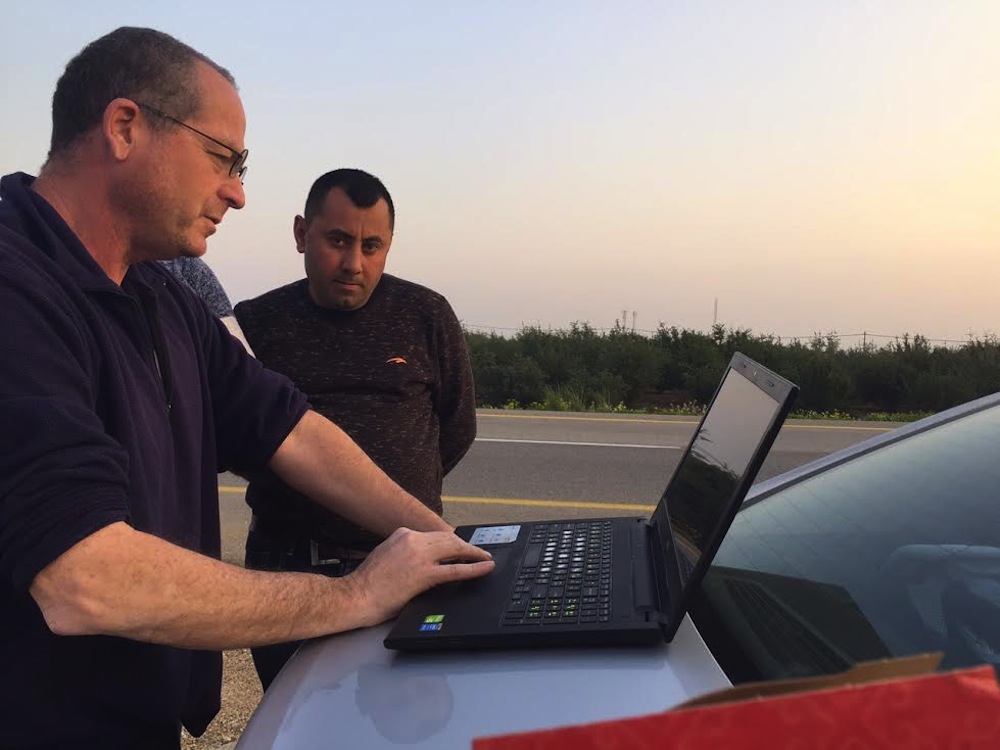

Etkes demonstrates the same kind of commitment to his monitoring of the settlements. Equipped with hundreds of aerial photographs that track changes on the ground in the West Bank, Etkes has taken it upon himself to memorize every nook and cranny of the settlement enterprise. But it is impossible to keep up with its unwavering force. The changes are countless and constant.

In the five decades since the occupation began, Israel has placed its Palestinian residents under a harsh military regime, while encouraging hundreds of thousands of Israeli citizens to move beyond the Green Line — in violation of international law — into the territory Palestinians hope will one day form an independent state. Successive Israeli governments — from both the left and the right — have established over a hundred settlements in the West Bank. Today, over 600,000 Israeli Jews live beyond the Green Line, constituting approximately 10 percent of the country’s Jewish population.

“See these caravans over here? See that guard?” Etkes exclaims as he points through the windshield. The Mazda careens to a halt at the northwestern edge of Alei Zahav, the fastest-growing settlement in the West Bank, built just a few kilometers east of the Green Line, where rows of white caravans have recently been erected. “These are all new. None of this existed just a few months ago,” he says, as the guard, a religious man armed with a rifle, makes eye contact. Alei Zahav looks like just about any Israeli suburb, built for the middle class of the religious-Zionist movement, the ideological heartbeat of the settlement movement.

In a sense, these enclaves are familiar territory for Etkes, and it shows in his daily interactions with settlers. His parents moved to Givat Hamivtar, a neighborhood in East Jerusalem, just a few years after Israel conquered the territory in 1967’s Six-Day War. “My parents viewed themselves as liberals, yet decided to build their home in East Jerusalem,” he says. “They were moderate — what some would call ‘enlightened.’ But their decision to move to occupied territory exposes the contradictions and the complexities of their identity.

“That’s why when I meet with people who trash settlers, I tell them, ‘Look at me — I’m a settler. In Israel it is very easy to become a settler.’”

The story of Etkes’ parents is not unlike that of many middle-class Israelis — many of them secular — who, following the 1967 war, flocked to residential neighborhoods over the Green Line, where property could be bought for next to nothing.

“I grew up in East Jerusalem, 1,000 feet from Palestinian homes. My childhood is a perfect example of the inability to look reality in the eye. One thousand feet from what we called ‘Arab homes.’ There was nothing in my childhood, including my parents or education, that pushed me to ask who or what existed there before.”

His connection to the West Bank, however, would only come decades later, in 1996, after he returned to Israel following an eight-year stint in the United States. Etkes began taking trips through the West Bank by bus, magnetized by a force that he couldn’t describe. This was half a decade before the checkpoints and settler-only roads that would be erected during the Second Intifada. “During the heyday of the Oslo Accords, everything was open,” he says, whizzing past Ni’ilin checkpoint, north of the Modi’in Illit settlement bloc. “Much of the infrastructure that both settlers and Palestinians use today simply didn’t exist. Today things are different.”

Etkes’ knowledge of the changing contours of the West Bank landed him in stints with Israeli human rights organizations Peace Now and Yesh Din, where for over a decade he focused on Israeli violations of private Palestinian land, further building his expertise and familiarity with the settlement movement and its modus operandi.

In 2010, Etkes left Yesh Din to found Kerem Navot, an NGO dedicated to tracking Israel’s land practices in the West Bank. The organization primarily publishes reports on various topics concerning land in the occupied territories. The aim of these reports, and the tours Etkes leads across the West Bank for Israelis and internationals, is to translate military policy into something the average person can wrap their head around.

His greatest success to date has been Amona, the crown jewel of the West Bank settlement outposts, which was built on private Palestinian land in the mid-‘90s. In 2005, Etkes was able to locate the landowners who, with the help of Yesh Din, took their case to the High Court of Justice. The court ordered nine homes demolished; years later, it would order the entire settlement dismantled. Yet the government came to a deal with the settlers, promising to reimburse them handsomely (approximately NIS 1 million per family) in exchange for moving to an adjacent plot of land.

When the settler movement realized Amona was a done deal, its representatives in the government rushed to pass the “Formalization Law,” which retroactively legalizes illegal outposts and allows the state (read: settlers) to merely use private Palestinian land rather than take ownership of it.

Amona’s blatant land grab can be blamed on a few dozen families, backed by the most zealous corners of the settlement enterprise. But the state actually has a far more efficient — and nefarious — way of expanding its territory in the West Bank, developed in response to early setbacks in the settlers’ attempts to take Palestinian land.

The settlement movement was impeded by the Israeli courts, which shot down method after method the settlers used to try and claim further territory. Another solution, a brand new system, would be necessary, and the answer was found in a distorted interpretation of the Ottoman land law, parts of which are still in force in the West Bank due to the way occupation law is set up.

Under the outdated Ottoman law, Israeli authorities decided that if they deemed land to be “insufficiently cultivated” for at least three years, they could declare it “state land.” Then Israel, or more precisely Israeli settlers, could do with that land whatever they pleased.

As a result, since the 1980s, the Israeli army has declared 187,000 acres of mostly Palestinian agricultural land as state land, on which the vast majority of settlements have been built. Massive reserves of state land are left over for future construction. The settlers’ desire to play by their own rules overcame whatever Israel was willing to give them.

But the settlement movement isn’t just looking to build a few new commuter suburbs, and the loose restraints put on its expansion had to be removed. In a sense, Amona and the formalization law are the Israeli Right’s last-ditch attempt to forgo the occupation’s bureaucracy. But the government is going to have a difficult time defending the blatant theft of private land.

“The Amona settlers did something incredibly stupid,” he continues. “They took a gamble and instead of taking advantage of the expansive reserves that Israel created through state land declarations, they built their outpost in an area even the government recognizes belongs to Palestinians. Bennett’s law is an attempt to undo all that — to make all private Palestinian land kosher for takeover.

“The minute land isn’t tended to by Palestinians on a regular basis — meaning the territory doesn’t have trees or isn’t being constantly farmed — that’s it. Soon enough it will belong to the state,” Etkes says. After that, it’s only a matter of time before settlers move in, often under the protection of the IDF.

Over the years, problems in the process of declaring state land resulted in enclaves of private Palestinian land left in the heart of settlements. One of the most glaring examples is in Modi’in Illit, a settlement populated by mostly ultra-Orthodox Jews, built on land belonging to five Palestinian villages. A short drive into the city is a valley that once belonged to Palestinian fellahin. Aerial photographs show a once green and fertile valley that farmers have been unable to tend to since the construction of the separation wall, which has expanded the settlement’s territory at the expense of Palestinian villages.

In 2006, the Modi’in Illit municipality began building a new five-acre park at the top of the valley, while erecting clusters of ramshackle caravans to house religious elementary schools at the foot of the valley. Etkes, who at the time tracked settlement construction for Peace Now, informed the Israeli military authorities that the park was being constructed without the proper permits, and that the area had been zoned as “public space” despite being privately owned. The army did nothing. Muhammad and Hamad Alhawaja, the owners of the land who live in the nearby village of Ni’ilin, are unlikely to see or work their land any time soon.

Palestinians don’t come here anymore

Israeli and international media often characterize the West Bank as a sort of Wild West. The description is not entirely untrue: lording over millions of Palestinians bereft of even the most basic political rights demands an entire system bogged down by a lack of coordination between its various legal and security bodies.

And into that chaos swept the settlement movement, which over the span of five decades has fashioned a reality that, Etkes believes, is almost entirely irreversible at this point. If chaos does indeed rule, then the 600,000 Israeli settlers living beyond the Green Line are its greatest benefactors.

Unlike the media portrayals, however, the settlement movement is not a monolith that simply swallowed the Israeli state whole. After 50 years, most of its victories have been won piecemeal — a plot of land here, an olive grove there.

Adjacent to Neria, a religious communal settlement of around 300 people located just south of the Talmonim bloc, is a small park full of dilapidated olive trees that once belonged to Palestinians. Picnics were a common sight here, with locals regularly coming to tend to the vegetation, as well as to an old sheikh’s tomb.

Today, the area is entirely abandoned — apart from a single memorial erected by a local settler council, welcoming you to “Gan HaNe’arim” (The Garden of the Teenagers), to commemorate the three Israeli teens who were kidnapped and murdered by Palestinian militants in the summer of 2014. It is also exemplary of how the settlers collude with the IDF to take over private Palestinian land.

“This is how it works,” Etkes says as he peruses the biblical verse etched on the memorial. “The settlers set their sights on a piece of land, and then through various means they make it theirs. In this case, it was a settler regional council that put up the memorial on private Palestinian land, essentially turning it into a park for the settlers of Neria. If a Palestinian comes here, he’ll either have to face the settlers or the army that protects them. Needless to say, Palestinians don’t come near anymore.

“For Israel as well as the settler movement, all Palestinian property is abandoned property,” Etkes remarks, adding that to turn someone’s land into a park or a school is only a matter of political will — and that will exists in spades.

After all, Etkes says, Israel’s policies of dispossession did not begin with a few religious extremists running amok in the hills of Samaria. “The settlements are not the result of a deep, inherent evil, rather of a mosaic of millions of tiny actions that are embedded in Israel’s foundation: the exclusivity of the Zionist project, which confers rights and privileges to one group over another.”