In a recent article, seasoned veteran of the Zionist Left Uri Avnery claimed that the influx of Russian-speaking immigrants to Israel, living in self-imposed ghettos, is what pushed the country to the right politically. Lia Tarachansky counters that the Russian-speaking community never ‘mingled’ with other Israelis because it was never invited to do so, and that Avnery is ignoring the many contributions the immigrants made to the country.

By Lia Tarachansky

I was born in Kiev into a shifting, uncertain reality. While I was only learning to read, my parents split, the Chernobyl nuclear reactor blew up and the Soviet Union collapsed. I was too young to understand what was happening when we evacuated the city and prepared for what would turn into years of economic devastation.

One night my mother woke my sister and I and told us to pack only what we absolutely couldn’t live without because we were moving to Israel. She told us Tel Aviv was lined with promenades where banana-eating monkeys sit in palm trees and that there we will no longer be “The Jews” because in Israel, everyone is Jewish.

In typical Soviet paranoia we weren’t allowed to tell anyone we were leaving. When we finally made it to the Romanian border after days on the train, we were stripped of our citizenship and promised we will never set foot again in the land where my parents and grandparents were born. My mother didn’t care. To this day she remains a dedicated Zionist even after learning that monkeys don’t sit in palm trees, that not only Jews live in Israel, and that indeed we are not all free.

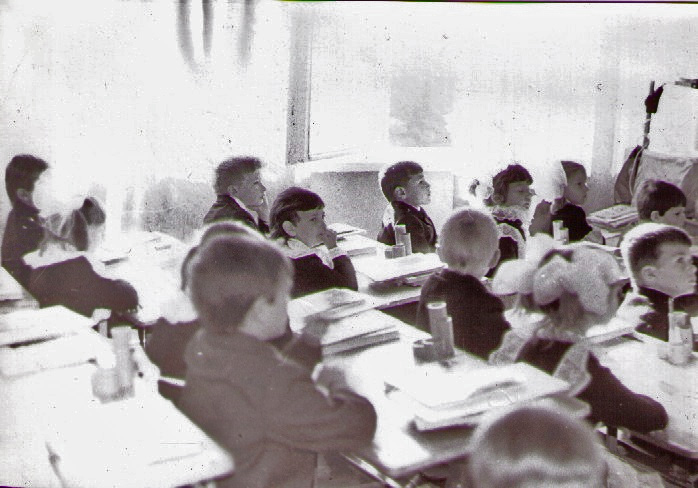

I went from being the only Jew in my Soviet kindergarten to being the only Russian in my Israeli elementary school. My mother went from being a computer engineer to changing diapers in a retirement home. In the Soviet Union we were hated because of our “piatii punkt” or “fifth clause” after the first and last name, date and place of birth; our nationality clause would read “Jew” on our identity documents. This is why the cynicism that dominates our community in Israel is so strong. We went from the façade of “equality for all comrades” to the façade of “equality for all Jews.”

Months later the rest of the Soviet immigration came, changing the demography of Israel just as it was coming out of the First Intifada. Once again, we were in the middle of uncertainty, discovering the Palestinians through the stories of our Israeli colleagues, bus drivers, and school teachers.

In his latest column, entitled “The Russians Came”, former Israeli Knesset member, renowned activist, and globally syndicated writer Uri Avnery wrote about our immigration. Despite often disagreeing with him, I read his columns regularly because he writes about interesting historical anecdotes picked up from being involved in the Israeli Left for 65 years. My criticism is the same as Tikva Honig-Parnass’s – that while he calls himself “post-Zionist,” Avnery represents the Israeli Left, which for the most part refuses to reject Jewish supremacy, Israeli colonialism, and draws the red line only at 1967, ignoring the entire ethnocratic ideology on which Israel was built in 1948. I’ve kept my criticisms to myself because Left sectarian politics and identity issues don’t interest me, but then I read Avnery’s latest column and my jaw dropped.

He complains that unlike previous waves of Jewish immigration to Israel, the Soviet immigrants “have not mingled at all.” That we remain “a separate community, living in a self-made ghetto.”

I don’t need to tell this publication’s readers that Israel is not kind to “the Other.” Like all our non-Ashkenazi predecessors, the Soviet immigrants couldn’t find professional work, faced discrimination on the street and were constantly harassed for not speaking the language well enough. We were stereotyped into gangsters, fascists, prostitutes, and street-cleaning PhDs. We were pressured to leave our culture and language behind to fit into the dominant “Israeliness” as many in my generation chose to do.

There was nothing self-made about our isolation. Most of the Russian-speaking community hasn’t mingled with other Israelis because it was never invited to do so. It was dumped with no government programs and no investment, to fend for itself in what in 1991 was a struggling economy emerging out of conflict. Even during the so-called “Israeli Summer” in 2011, when hundreds of thousands took to the streets, the handful of us who came out to demonstrate week after week were received with either tokenism or suspicion.

Avnery complains that we “continue to speak Russian,” and read our own Russian newspapers, “all of them rabidly nationalist and racist,” which is why, he claims, we all vote for Israel Beiteinu. Watching Channel 9, the Russian-language Israeli TV station, I agree that it is indeed abhorrent, but it is so because it emerged from a state with no history of independent media into a state with a complacent, nationalistic, and war-mongering media.

What enraged me was not only that Avnery doesn’t talk about the contribution the Soviet immigration made to the boom in the high-tech industry on which Israel now depends, about how we revolutionized theater and cinema, or how we, like my family, were encouraged to move to the settlements in the West Bank while the ink on the Oslo agreements hadn’t even dried.

What enraged me was his accusation that it was the Soviet immigration which turned Israel to the right. He comes to this insane conclusion that “the Arabs and many of the Ashkenazim [Western European Jews] belong to the peace camp, all the others are solidly right-wing.”

We had come out of Soviet anti-Semitism into a country in conflict, where we were told that the violence we were seeing was driven by rabid Jew-hatred. It is no wonder that we transferred much of our fear and distrust of Soviet anti-Semitism to the Palestinians. Now, more than 20 years later, Israelis are witnessing the result.

We didn’t make Israel a colonial state. Like every wave of immigration before us, we did our best to fit into it. Avnery portrays the Ashkenazim as the peace-seekers, but it was the European colonial mentality that started and perpetuates this mess. Some settlers are violent but what they are doing in the West Bank doesn’t come close to what Avnery and the Ashkenazim did to the Palestinians in 1948 when more than 500 villages were demolished and two-thirds of the population was kicked out.

Overbearing dominant nationalism creates overbearing nationalistic citizens. I will therefore conclude with Tikva Honig-Parnass’ words. She, like Avnery, fought in the 1948 war and took part in the mass dispossession of the Palestinians. “There was never an actual schism between Left and Right about the central premises of Zionism. The only difference… was in the sequence of the stages that the project of an exclusivist Jewish state in the entire area of historical Palestine had to take in order to achieve its aims.”

Lia Tarachansky is an Israeli-Canadian filmmaker and journalist. Her work has appeared on The Real News Network, Al Jazeera, USA Today, and The Huffington Post. Tarachansky’s upcoming documentary, Seven Deadly Myths, profiles Israeli denial of the events of 1948 and the roots of the modern conflict. The trailer and details on how to support it are available online at www.sevendeadlymyths.com.