As President Trump seeks to maintain white Christian hegemony, the Jewish state can serve as a case study of nationalism run amuck — and what that means for the ‘others’ who live there.

Israel’s founding premise that it would be a “Jewish and democratic” state has always meant that if the state wants to remain democratic it must maintain a Jewish majority. Artificially maintaining a certain ethno-religious majority has led Israel to take some decidedly undemocratic measures against various minority populations.

In the United States these days, President Donald Trump is also seeking to maintain a particular ethno-religious hegemony — that of white Christians. What does that mean for the future of the United States and its democratic institutions? Israel, where questions of national identity take on existential proportions, can provide important lessons. The Jewish state can serve as a case study of nationalism run amuck and what that means for the “others”—in this case, non-Jews—who live there.

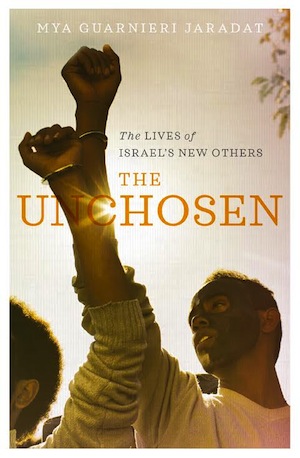

My new book, “The Unchosen: The Lives of Israel’s New Others,” focuses on two groups of “others” in Israel: migrant workers from Southeast Asia and African asylum seekers. Significantly, a large number of the asylum seekers in Israel are from Sudan, one of the countries on Trump’s “travel ban” list, which has also been referred to as the “Muslim ban.” Who are these people that are targeted by both Trump and Israel? Why did they leave Sudan? What were they escaping? What are their hopes and dreams for the future?

“The Unchosen” offers an intimate look at the lives of Sudanese asylum seekers. Almost all African asylum seekers in Israel are denied legal status — and while Israel claims that they’re actually illegal work migrants, the state can’t deport them because to do so would violate the international law against repatriating asylum seekers to a country where they could face persecution or death. So Israel keeps them in legal limbo, hoping that they will “self-deport” if you will.

To maintain its Jewish majority, Israel uses a variety of policies that, taken together, also constitute a Muslim ban. Palestinian refugees cannot return to the lands they lost during the 1948 war. For nearly 15 years, a law banning family unification means that if a Palestinian from the West Bank or Gaza marries a Palestinian who lives in Israel, they cannot come to Israel to reside with their spouse. The same is true of non-Jewish citizens of Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon who might marry a citizen of Israel – there is no legal avenue for them to actually live with their spouse in Israel.

Another, more commonly cited parallel, is the separation barrier Israel built along its southern border with Egypt to stop Sudanese and Eritrean asylum seekers from entering the country. A key component of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign was his promise to build a wall along the the United States’ southern border with Mexico. While many observers liken Trump’s proposed wall to the one that stands between Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories, the barrier between Israel and Egypt is more analogous.

Why? First of all, the African asylum seekers who used to enter through Israel’s southern border have been falsely portrayed by both the Israeli government and Israeli media as “work migrants” or “work infiltrators” or just “infiltrators.” They’ve been depicted as people who rob Israelis of jobs, who rape, who sell drugs, who pose a threat to the very character of the country.

Sound familiar? It’s almost identical to the way Trump depicts Latino immigrants.

In the U.S. right now, authorities are putting increasing pressure on undocumented immigrants, many of whom are migrant workers. In addition to its in-depth discussion of the lives of African asylum seekers in Israel, “The Unchosen” details the struggles of Christian Filipino migrant workers and their Israel-born children — offering a look at the lives of those who don’t fit the Jewish’s state’s preferred ethno-religious background, and the impact of the policies designed to prevent them and other non-Jews from settling in Israel.

And what might all this mean for the United States’ democratic institutions?

Activists in the U.S. hailed the Trump administration’s backtracking from the original travel ban — as a result of a temporary court ruling as a victory. But a certain case in Israel suggests that, if there is a protracted battle over the ban — like with the White House issuing a slightly modified version of the same order — it could end up eroding the country’s democracy and its democratic institutions.

In Israel, too, every time the country’s High Court struck down a law designed to deter and make miserable African asylum seekers, the Israeli parliament crafted a new, slightly modified version, in an attempt to circumvent the High Court’s ruling. That continual ping-ponging between the Knesset and High Court has called into question the health of Israel’s democratic framework, evidencing the way the state often finds ways to sidestep — if not outright disregard — the rulings of the highest court of the land. In Israel, the lack of a formal system of checks and balances makes such games dangerous yet leaves enough flexibility to avert a full-on constitutional crisis: the stakes of a direct confrontation between the Executive and the Judiciary in Washington are far higher.