The nativist rabble-rousing and promises of expulsion and exclusion that carried Donald Trump to victory are worryingly similar to the resurgence of Meir Kahane’s Kach movement in Israel. Neither can be ignored.

On the eve of the U.S. presidential elections I stood opposite an alcove in Kraków’s High Synagogue, gazing into an empty socket in which a Torah scroll once stood. The synagogue — named for the fact that the prayer hall was installed on the first floor, in order to protect its Jewish congregants from the Christian gathering-places nearby — is no longer active, but evidence of its past remains: the circular window at the top of the building, the case of tattered religious books, the patches of Hebrew murals that look like scraps of parchment rescued from a fire. But it is the Torah ark and its present-absent void that offers the starkest metaphor for what had been and is no longer.

I looked into that empty space believing that the following day, I would watch the U.S. deliver a resounding rebuke to the kind of ideology and rhetoric that can snowball into such crimes. Forty-eight hours later, the extent of my misplaced confidence has been made crystal clear. As a queer Jew, I am deeply disturbed by what has happened in the U.S.; as a woman, I’m furious. And as a British-Israeli, I’m wondering how many more godawful Groundhog Days there will be to come.

Indeed, the scale of the challenge now facing America, and by extension much of the world, will be familiar to many Israelis. Just like Netanyahu, Trump lied, bullied, fear-mongered and incited his way to the nation’s highest office, and there is so far little evidence to suggest that his approach, demeanor and cataloging of personal vendettas will cease once he’s in the Oval Office. The current witch-hunt in Israel against an amorphous, elastically-defined left-wing “elite” — as the populist Right defines it — is also an ominous portent of what could develop in the U.S., including the demonization of and call for restrictions on the free media.

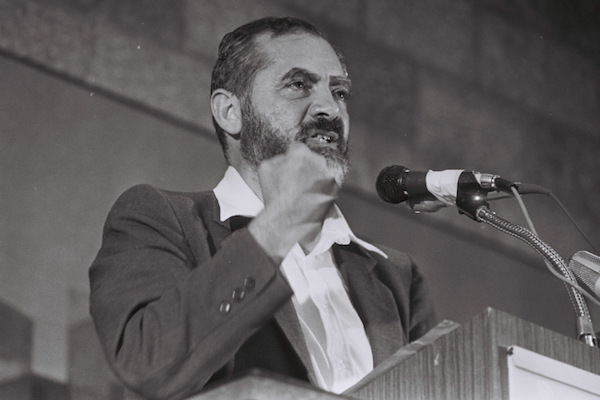

An additional parallel with Israel is more disturbing still. Even if the unthinkable happens and the pivot that Trump proved incapable of as a candidate materializes when he is president, the swirling currents of violent and unabashed misogyny, racism, anti-Semitism and Islamophobia will be extremely difficult to bottle back up. In the mid-1980s, the virulent anti-Arab racist and anti-miscegenist Rabbi Meir Kahane — whose philosophy is the engine behind newer radical right-wing groups such as the Lehava — won a seat on the Knesset after running on a ticket of nativism that name-checked expulsion, exclusion and self-ghettoization.

Sound familiar? The key difference is that Kahane’s party, Kach, was outlawed in Israel for its promotion of violent racism, and Kahane himself was assassinated in New York in 1990. Yet his failure to build a successful and viable political movement did nothing to stop the spread of Kahanism; the racist, street-level thuggery, anti-democratic discourse and ethnic supremacist posturing that blights Israel today is his legacy. Even as analysts predicted that Kach’s banning marked the decline of Israel’s radical right after the pandemonium it sowed in the 1980s, his ideology somehow bloomed in the desert. But Trumpism has suffered no such setback. On the contrary: his election night victory was the ultimate endorsement of the newly savage sociopolitical reality he has fostered.

Yet there is one more parallel, and one I feel it’s important to end on. Even as the Israeli political establishment gradually catches up to Kahanism, activists, civil society workers and human rights advocates continue, every day, to press for the changes they want to see in their country. In the face of grim predictions for Israel’s future, violence both threatened and inflicted, and the ever-increasing glowering scrutiny of the government, they continue to fight — via campaigns, in the courtroom, on the ground and, yes, at the polls.

So it can be in the U.S., as well as in the UK, still reeling from a Brexit vote that claimed victory on the back of the same wave of bigoted right-wing populism that swept Trump into power. There can be time to mourn, to give space to our shock and anger, and to question what we got wrong, and how.

But after that comes the work — the organizing, the encouragement, and the challenge of listening when all we want to do is shout. The groups and individuals around us most threatened by what Trump, and to a lesser extent Brexit, represent — people of color, Muslims, LGBTQs, women, and particularly those who inhabit more than one of those identities — have been among the most vocal and effective advocates for change and social justice over the last tumultuous year. We must all play a part in ensuring that work continues, whether we are members of those communities or not.

I have quoted the poet Dylan Thomas before, but I am repeating these lines here, for never have they felt so necessary:

“Do not go gentle into that good night,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”