For years I have been escorting Mohammed and Maha to an Israeli hospital and back to Gaza. That is, except for those times when Israel denies him an entry permit. This week, as the illusory stability of daily routine disintegrates around us, something feels different.

By Deb Reich

We had stopped in a giant shopping center near Ashkelon on the way south to find Mohammed a new pair of sunglasses, because some kid in Gaza stole his recently. We hadn’t found any that he liked in Jaffa, where we lunched together as usual after Mohammed’s clinic check-ups at Tel Hashomer Hospital in Tel Aviv. For young Mohammed Mehanna, his aunt Maha Mehanna, and me, this has been a long-established routine every few months for the last several years, except every once in a while when despite Mohammed being due at the hospital he and Maha don’t get permits to leave Gaza.

Since his 2008 bone marrow transplant at the age of 14, Mohammed needs good sunglasses because of a problem with GVHD (graft-versus-host-disease) of the ocular cavities. Meantime at the shopping center, while I parked the car, he and Maha surveyed the ice cream on offer. I shouldn’t have sent them on ahead. What was I thinking? I came hurrying over to find two security guys in reflective vests, standing maybe two meters away, facing in their direction, speaking Hebrew. The thought crossed my mind – Jeez, guys, don’t shoot them before I can explain in Hebrew that they’re not terrorists.

The guards moved on. I’m not even sure they had been looking at Maha and Mohammed, but the very real potential for disaster was creepy. It was October 29, 2015 in Israel. The illusory stability of daily routine was disintegrating all around us.

At this mall near Ashkelon, an area with virtually no Palestinian residents after 1948, the young ice cream barista clearly didn’t know what to make of our mixed little Arab-Jewish group, yet she seemed okay with us and served us politely. I left a tip.

Ice cream cones in hand, and conscious of needing to reach the Erez crossing by 7 p.m. (Erez is the only passenger crossing between Gaza and Israel), we decide to try the supermarket and SuperPharm for shades. Tired, I said I’d sit in the car while they go in. Mohammed said something I didn’t quite catch, and Maha turned to me and explained: “He says he’s afraid we might get attacked without you.” Too right, I thought. How fucking sad.

On to the supermarket, which had no shades for sale. The local shoppers, all Israelis, noticed us and were covertly perturbed, but no one attacked us either. (Whew.)

At the SuperPharm, we got some dark looks. I thought our slurping ice cream while shopping might have been a factor, but the rest of the unwelcoming behavior in the store, if we’re being honest, was about Maha’s hijab and the inference that Mohammed must also be “them” and not “us.” The customers and cashiers were not overtly hostile, they really weren’t – just covertly terrified. Sad sad sad.

I maintained a jolly front on general principle. We got Mohammed a nice pair of shades, on sale, for about $14. The ice cream was great. We made it to Erez by 7:05. Arrive too late and you risk a long wait to cross. In the morning there had been a five-hour delay because all the checkpoint personnel were in a meeting and there had been some kind of screw-up with Mohammed’s permit; fortunately, the Israeli who had volunteered to drive them to the hospital that morning had stayed the course and was there waiting when they finally got out.

Usually, returning with them at night, I drive defiantly past the parking lot, almost to the guarded gate, make a U turn onto the dirt shoulder, and park there. We disembark along with whatever purchases or gifts they are bringing home, and we have our bear hugs, smiling in despair and clutching each other. I hate leaving them there. I hate it.

This time, I said to Maha as we drove past the guard tower toward the gate: I think maybe tonight I won’t drive us that far. Too close. They might get nervous and shoot us.

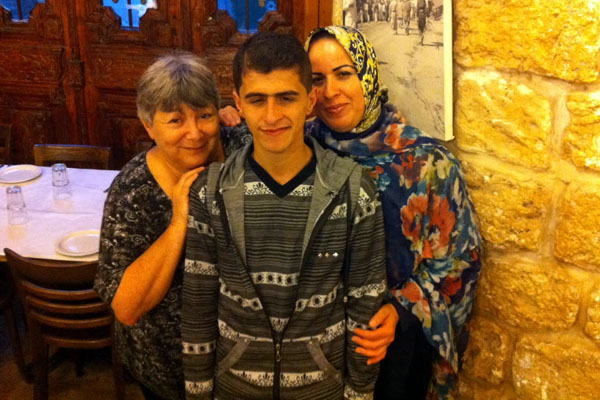

So we stop farther away this time. It was one day after Mohammed’s 21st birthday and we had been happy the whole time, at least until Ashkelon. Three out of the 12 million people between the Jordan River and the sea were winding up a great shared day irrespective of all that is done to divide us. Most of the others were engaged in fear and loathing, military actions, and survival manoeuvres.

Planet of the Damned.

Deb Reich, a writer and translator, is the author of ‘No More Enemies’ (2011), described at www.NoMoreEnemies.net Contact her through the web site or at debmail@alum.barnard.edu