The last time there was a wide-open Democratic Party primary, Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama clashed on everything from the Iraq War to health care to race. Everything, that is, except for Israel.

Criticism of Israel during the 2007-2008 race was limited to fringe candidates. In a 2007 NPR debate, Mike Gravel, the gadfly former Senator from Alaska who never polled higher than 3 percent, asked why it was a problem that Iran funded Hamas and Hezbollah, while the U.S. funds Israel.

That was one of the only deviations from the standard pro-Israel line aired during the primary season — and the candidate making it wasn’t exactly a star. Gravel didn’t win a single delegate. While Clinton and Obama dutifully voiced support for Israel throughout the campaign, the U.S.-Israel relationship didn’t occupy a central place in the Democratic primary race.

A decade later, the debate over Israel has radically changed. It’s now playing out on the most prominent stage of American politics — the presidential race — and in the halls of Congress.

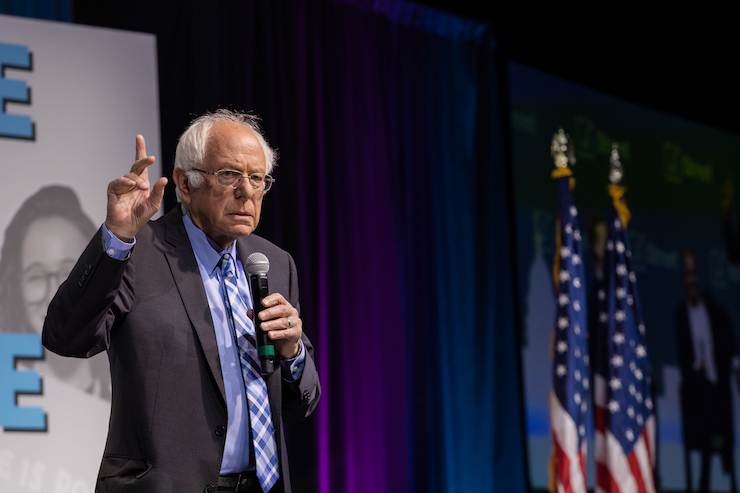

Senator Bernie Sanders (D-Vt.), who is polling third in the race to be the next Democratic presidential candidate, has repeatedly said he wants the U.S. to leverage its military aid to Israel to end Israel’s unjust treatment of Palestinians. Pete Buttigieg, the Indiana mayor polling in fourth place, said U.S. taxpayers should not foot the bill for an Israeli annexation of the West Bank. Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), now battling for front-runner status with Joe Biden, has been less clear about her plan for Israel-Palestine. But she has spoken about the need for an end to Israel’s occupation, and in October, said she was open to conditioning U.S. military aid to Israel. As for Biden, he’s alone in saying that conditioning U.S. military aid to Israel would be “absolutely outrageous.”

Meanwhile, a new crop of progressives, led by Reps. Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.) and Rashida Tlaib (D-Mich.), are widening the debate on the U.S.-Israel alliance in Congress, calling for limits to U.S. military aid and hailing the tactics of boycott, divestment and sanctions as tools to change the status quo on the ground.

“There’s an increasing openness and willingness to talk in much more depth, and much more even-handedly, about the realities of the Israel-Palestine conflict,” said Logan Bayroff, spokesperson for J Street, the liberal, pro-Israel Jewish-American lobbying group. “A lot more space has opened up over the past 10 years, and especially over the past four years, during the Trump administration.”

This evolution is not incidental. The dramatic change in the U.S. debate over Israel-Palestine is the result of long-brewing shifts in party ideology, a series of striking events in Israel and the U.S and dogged organizing led by Palestinian-Americans that has capitalized on these trends. The result of all this? A lively debate over the future of the U.S.-Israel relationship that shows no sign of dying down.

The Jewish state is no stranger to Washington politics. Even before President Harry Truman recognized Israel in 1948, American Jews were in the capitol, lobbying Truman to support turning then-majority-Arab Palestine into a Jewish state.

For much of the seven decades since, U.S. discussion over Israel in Washington has centered on how best to protect the Jewish state from its hostile neighbors.

There have been occasional interruptions to the status quo. In the early 1980s, President Ronald Reagan suspended fighter jet deliveries to Israel after the bombing of an Iraqi nuclear reactor, and prohibited exports of cluster bombs after Israel dropped them on Lebanon during Israel’s first war there. In 1992, President George H.W. Bush refused to approve loan guarantees for Israel unless it stopped building settlements on Palestinian land in the West Bank and Gaza.

These occasional shifts in the American political debate on Israel did not, however, undermine the ironclad U.S.-Israel alliance. And eventually, these breaks in the status quo debate withered away.

The polarization of Washington politics in recent years, however, paved the way for today’s partisan divide on Israel. The Republican Party grew whiter, older, and wealthier. Right-wing Christian evangelical influence over the GOP grew considerably, pushing the Republican Party’s policies on Israel far to the right. The Democratic Party became more reliant on people of color, young people, secular people and religious minorities. Both parties’ rank-and-file coalesced around two fundamentally different visions of how America should conduct itself in the world. The September 11, 2001 attacks temporarily united the Democratic establishment and the GOP to wage the Iraq War, but in progressive spaces, anti-war sentiment was high. And with it, more attention was paid to the issue of Palestine, although Palestine was a divisive issue at times. Some liberals did not want to connect Palestine to Iraq, while those more firmly on the left saw them as interconnected issues.

“They started making connections between what was happening domestically and what was happening in Israel, because Israel was making that connection in terms of its hasbara campaign,” said Zaha Hassan, a visiting fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “They said Palestinian resistance in the occupied territories was no different than Islamic extremist movements in the Middle East. Liberals and progressives in the U.S. started to consider whether the values their movement espouses can consistently continue to support Israel without considering Palestinian human rights.”

It was common at the height of Iraq War protests to see the Palestinian flag flying, to hear the chant “From Iraq to Palestine, occupation is a crime!” The linkage of the struggle against U.S. empire to Palestine echoed the late 1960s, when Black Power activists advanced an internationalist lens that connected the struggle of Black people in the U.S. to anti-colonial struggles the world over, Palestine included. In the post-9/11 era, then, as in the late 1960s, divisions on the streets over Israel-Palestine did not translate into a break in the Washington consensus on Israel. Instead, it would take until the Obama years for skepticism of Israel to enter into the heart of debate in DC.

Barack Obama’s election as president came as a shock to a country used to white men occupying the White House. He also promised to break from the wars of the Bush era and to mend relations with the Arab and Muslim world post-9/11, a promise he tried to honor by making the Middle East his first visit overseas. There, he pledged a new era in U.S. policy.

One of those new policy areas was Israel-Palestine. After taking office in January 2009, he called Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas before he rang Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert, who would soon leave office in disgrace, to be succeeded by Benjamin Netanyahu. In his trip to the Middle East, Obama didn’t touch down in Israel — instead, he went to Cairo, where he criticized Palestinian violence but called on Israel to stop building settlements and to address the humanitarian crisis in Gaza.

Rebuffed by Netanyahu, whose government continued to build Israeli settlements, Obama never followed up his demands with consequences. But Obama’s calls for a settlement freeze, coupled with Netanyahu’s cold response, laid the groundwork for how toxic the Obama-Netanyahu relationship would become.

These tensions reached a high in 2013 with the debate over the Iran nuclear deal. Obama’s decision to strike a deal with Iran made Netanyahu and his Republican allies go apoplectic. In their eyes, the deal would give Iran access to the global economy while doing nothing to constrain its funding of militant groups opposed to U.S. policy in the region. For Netanyahu, it also undermined Iran’s role as a distraction from the Palestinian issue.

The GOP invited Netanyahu to deliver a speech before Congress in order to try and thwart the deal. This set up a startling political clash between Obama, the historic president beloved by his party’s base, on one side, and the GOP and Israel on the other, heightening the partisan divide on the Jewish state.

“Republicans thought Netanyahu was the single most important world leader at that time — even above Reagan. He became a star, as if he was the guru of the Republican party,” said Shibley Telhami, a professor at the University of Maryland and a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. “For Democrats, it was exactly the opposite. That had a huge impact.”

Telhami, a pollster, saw that impact in a December 2015 survey he conducted: Netanyahu’s unfavorable ratings among Democrats shot up from 22 percent to 34 percent. Thirteen percent of Republicans viewed the Israeli leader badly, and 51 percent viewed him favorably.

When Netanyahu arrived in Washington in March 2015 to rail against the Iran deal, 58 Democrats and independents who caucus with Democrats boycotted the speech.

Criticism of Israel in the Obama era was not limited to Congress. It was even more salient in progressive social movements, which in turn gave Democrats confidence that their anti-Netanyahu stance was backed up by the grassroots that vote for them.

By the time the Obama-Netanyahu clash over Iran took place, more and more Palestinian rights groups were devoting resources to Washington. In 2015, Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP), the left-wing Palestine solidarity group, hired their first employee focused on Congress.

“[The] 2014 [assault in Gaza] happened, then all of a sudden we were much, much bigger,” said Rebecca Vilkomerson, who has just stepped down as head of JVP after 10 years at the helm. “We decided we had enough members with enough chapters that it wasn’t just going to be pointless to go do these kinds of meetings [in Congress].”

Also in late 2014, Defense for Children International-Palestine and the American Friends Service Committee started the “No Way To Treat a Child” campaign, a Washington-centered effort to get U.S. lawmakers to speak out against Israel’s mistreatment of Palestinian children. That effort has found success, particularly in the figure of Rep. Betty McCollum (D-Minn.): with her bills and letters calling attention to Israel’s arrest of Palestinian children, she has become the leading champion for Palestinian rights on Capitol Hill.

All of the liberal-left groups did not work in concert, however. J Street, for instance, a group that started in 2007, has carved out a distinct space on Capitol Hill: pushing for a Palestinian state and an end to Israel’s occupation to allow Israel to remain “Jewish and democratic,” in J Street’s words. That runs counter to groups like JVP and the US Campaign for Palestinian Rights (USCPR), both of whom support the full planks of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) call — including Palestinian refugees’ right of return — and cutting off U.S. military aid. Still, taken together, groups from J Street to the US Campaign have introduced a new side to a debate that used to be dominated by Israeli security concerns alone.

“Even though the other side has far, far more resources and deeper relationships, Palestinian rights groups have done hard, diligent work in making their presence felt on the Hill, making clear that there is another perspective that members of Congress need to acknowledge, even if they don’t yet feel the need to vote that way,” a senior Democratic Congressional aide told +972. “That is how you shift the debate. You start to complicate the issue for people, and for too many members of Congress the issue has been uncomplicated. That’s changing.”

But if the debate in Washington focused on Netanyahu, left-wing social movements were not primarily focused on the Israeli leader. Instead, they were focused on Israel itself, and they criticized the entire regime that ruled over Palestinians as akin to an apartheid state, and one that needed to be boycotted — a message spread through BDS campaigns. Palestinian rights groups allied with immigrant and civil rights groups for campaigns that took aim at private prison profiteers, using the message that the oppression of people of color in prison is linked to the oppression of Palestinians — especially because companies like G4S profited from the imprisonment of all of those communities. Students for Justice in Palestine chapters formed coalitions with communities of color on campus to push for their student governments to endorse divestment from corporations that profit from Israel’s occupation.

Much of this student work was led by Palestinians themselves, an echo of the work groups like the General Union of Palestinian Students did on U.S. campuses starting after the 1967 War. After the Oslo Accords, Palestinian-led activism in the U.S. faltered, as more attention was paid to state-building back home rather than forming a global anti-colonial movement. But Palestinian organizers reasserted themselves in the broader solidarity movement once the Oslo Accords failed. That resurgence reached a peak following Israel’s 2008-2009 invasion of Gaza.

“Palestinians started to be centered more, which also meant that Palestinian organizers rose,” said Andrew Kadi, a long-time Palestinian-American organizer and steering committee member of the USCPR.

One of the most important moments for the Palestinian rights movement came in August 2016, when A Vision for Black Lives, a policy platform published by groups affiliated with the decentralized Black Lives Matter movement, endorsed divestment from Israel’s “military-industrial complex” and accused Israel of apartheid and genocide. For Palestinian rights groups, the policy platform was a prime example of how the Black freedom struggle and the Palestinian struggle should be connected. It was a ringing affirmation of their “intersectional” strategy, which made sure Palestinians advocated for the rights of Black people in the U.S., and vice versa, as part of a larger push to connect the Palestinian and Black struggles for justice.

“You have a situation now where social movements are deeply interconnected,” said Nadia Ben Youssef, advocacy director at the Center for Constitutional Rights. “We’re creating a coherent politics of social justice, that if you have an opinion on racial justice, if you have an opinion on incarceration, if you have an opinion on inequality more broadly, you have an opinion on Palestine.”

By the time the shock of the 2016 election came, the broad left had come to recognize that Palestinian rights should be an integral part of the progressive agenda. Linda Sarsour, a prominent Palestinian-American activist, was one of the faces of the historic Women’s March against Trump in January 2017. But Palestinian rights’ integration into the progressive movement did not come without controversy. Pro-Israel groups slammed Sarsour and the Movement for Black Lives. They were accused of hijacking the progressive movement with a totally different agenda. It became untenable for progressives to ignore Palestine, though.

That has become even more apparent as progressive officials like Ilhan Omar, elected in 2016, have taken on the fight for everything from Medicare for All to the Green New Deal to an end to Israel’s occupation. Omar’s foreign policy vision centers on demilitarization and human rights, with no exception carved out for Israel’s treatment of Palestinians.

The election of Trump has turbocharged the politics of Palestine in the U.S. His tight alliance with Netanyahu has alienated liberal Democrats from Israel. Trump’s gifts to the Israeli right — the moving of the U.S. embassy to Jerusalem, the administration’s silence on Israeli settlements and recognition of the Golan Heights as Israeli territory — further linked him to Netanyahu, a problem for those who believe in the importance of a bipartisan relationship with the Jewish state.

Trump has also pursued another strategy that has brought Israel-Palestine into the heart of American debate: labeling fervent critics of his like Omar and Tlaib “anti-Semites,” as part of a bid to split the Democratic Party, peel off Jewish voters and excite his right-wing base.

“You’ve seen the GOP try to turn it into a political weapon, a wedge issue. It becomes a red-meat culture war issue, like abortion or immigration,” said Logan Bayroff, the J Street spokesperson. “This riles up their base voters, which aren’t American Jews but are a lot of evangelical voters, which are driving that agenda.”

Netanyahu’s decision last August to ban Omar and Tlaib from traveling to Israel-Palestine on a Congressional delegation was part of Trump’s strategy to paint them as enemies of Israel and America. By helping create a headline-grabbing international controversy, Trump advanced his plans to make Omar and Tlaib the faces of the Democratic Party, a strategy he believes will win over people worried about Democrats racing to the left.

But that decision also had a boomerang effect. Omar and Tlaib held a remarkable press conference after the ban was announced, speaking to a nationally-broadcasted audience about the indignities of the occupation and how Israel harms Palestinians. It was, in a single week, an encapsulation of how Palestine has moved from the margins to the mainstream of American politics. On the right, it’s used as a wedge issue, while on the left, it’s amplified by progressive lawmakers who view Palestine as part of their larger agenda for social justice.

For Democrats who want to maintain the U.S.-Israel alliance as it is, Netanyahu’s decision to ban Tlaib and Omar was worrisome, and only furthered their desire to see Netanyahu leave office and have someone like Benny Gantz, the head of the Blue and White party, take over. In their eyes, that would allow Democrats to get back to their usual place on Israel: supporting negotiations between Israel and the Palestinian Authority without the nuisance of a nakedly partisan Netanyahu straining the U.S.-Israel relationship.

But while a Gantz premiership may give such Democrats a breather from the chaos of the Netanyahu-Trump era, it won’t end progressive questioning of the Washington consensus on Israel.

“There are a lot of Democrats under the illusion that the problem is just Bibi. But we shouldn’t personalize this too much,” the senior Democratic Congressional aide said. “Yes, Bibi is uniquely bad, particularly blatant in his partisan approach, but like Trump, Bibi is the product of a genuine political trend in Israel. He represents an illiberal constituency that Democrats need to confront if they’re serious about their own professed values.”