At the end of the first play in Mona Mansour’s “The Vagrant Trilogy,” which opened in New York last month after a two-year pandemic-induced delay, Adham, a Palestinian academic, is arguing with his wife, Abir, over whether to remain in London or return to Palestine at the outbreak of the 1967 war. Adham, a scholar of the English poet William Wordsworth, wants to stay, rooted to the spot by the dream of academic success now flashing before his eyes; Abir, who has followed him to England, insists they return home and reunite with their respective families, whom they have been unable to contact since the war started.

As the two wrestle over what staying or leaving would spell for each of them, Abir, reacting to Adham’s insistence on throwing his lot in with England, and his incredulity that she might not want to do the same, finally snaps — “This feels like nowhere to me!” — before walking out, determined to return to Palestine, and leaving Adham on his own in London.

It’s a striking line in a play that grapples so unflinchingly with place, displacement, and belonging. And indeed, over the course of “The Vagrant Trilogy” — a trio of interlocking one-act plays performed together — the question of whether Adham stays or leaves is not exactly resolved one way or the other: the narrative’s “conditional” structure sees the second play, “The Vagrant,” set in London in 1982, explore what would have happened had Adham remained in England; the third and final play, “Urge for Going,” set in a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon in the early 2000s, looks at Adham’s life as it would have been had he returned home. (The first play in the trilogy is titled “The Hour of Feeling.”)

Along with Adham and Abir, we meet Adham’s family — his mother, brother, and children — and an array of professors and students at the prestigious London university where Adham ends up teaching during the period covered by the second play. Among the academic characters are numerous well-meaning white liberals and radicals who, at various junctures in which historical events collide disastrously with Adham’s (and his family’s) own life, are seemingly oblivious to how their self-satisfied political banter is painting crude brushstrokes about the displaced Palestinian man before them.

I saw the play about halfway through its six-week run, which ended on May 15, along with a sold-out crowd in New York that gave a standing ovation at the curtain call. The performance began with a show of levity — in a brief prologue, the cast introduced Adham and the play almost in the form of a Greek chorus, with a wry reference to the movie “Sliding Doors” letting the audience know what to expect — but rapidly added layers of complexity, examining how to navigate the unimaginable loss that accompanies displacement; the many and sometimes disparate selves that form in response to that rupture; and what counts as staying and what counts as leaving for a character like Adham, who is struggling to find his place in the world.

“I think he’s an exile from himself,” Mansour tells +972 Magazine, describing Adham, and his relationship to Palestine. “He tells himself he doesn’t need to be in Palestine… This is a man who’s not conscious of what it is he’s missed and is missing.

“He is not reconciled with his own trauma, he has not reconciled his leaving with the choice he made in 1967.”

Mansour, who was born and raised in southern California after her father left Lebanon for the United States on the brink of the 1958 civil war, was in part driven to write these plays as a way of exploring the emotional and psychological impact of displacement and the refugee experience. In the course of researching and writing them, she says, she reckoned with both the long-term limbo in which displaced Palestinians find themselves — of being “temporarily” in a refugee camp for over 70 years — and with “the idea that you’re not of the place you left or were forced out of, and you won’t be of the place you’ve gone to either,” and how that plays out in successive generations.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

You’ve been working on The Vagrant Trilogy on and off for over 10 years. What was the catalyst for you to start developing this play? And was there a particular character or narrative thread that came to you first?

I’ve tried to hunt down my first scratchings on this play. The first play I wrote in the trilogy was the third one, set in the refugee camp. I had this inchoate desire to explore my father’s country: he’s from a village in southern Lebanon which, as I began to understand it as a kid, was next to a Palestinian refugee camp — Mieh-Mieh, which literally translates as “A Hundred by a Hundred.” It’s a short drive from Sidon, otherwise known as Sayda, where you have the camp ‘Ayn al-Hilweh [the largest Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon].

The question of Palestine, and the narrative of Palestine and Lebanon’s politics, was part of the bread and butter conversation in my home growing up. We were surrounded by cousins and uncles who were basically fleeing the civil war from 1975-1990. So I’d always just known about [Palestinian refugees in Lebanon] — that there was this population there. My family was not necessarily “pro-Palestine,” but there was a strong reverberation in my house when certain things happened.

So when I started working on “Urge for Going,” and when I started to do all this research on Palestinians in Lebanese camps, I couldn’t get past the simple fact of being in this camp since ’48, yet it’s “temporary.” What is it like to be waiting, to be unable to build — you can’t build out, you can only build up — and be blocked from obtaining dozens of jobs? So as well as being stateless, Palestinians in Lebanon have this remarkable lack of any social mobility.

I got into the Emerging Writers’ Group at New York’s Public Theater [in 2009] based on that play. I suppose, looking back, I shouldn’t understate how important it is that that’s the play I sent in; there is censorship in theater, there are plays that don’t get done. So the fact that I got into the Emerging Writers’ Group based on that play told me they were ready for this kind of material.

At that point, I wanted to explore what Adham was like before this [displacement] happened to him. I was then tapping again into aspects of my own father who, while not Palestinian, did leave Lebanon in the late ’50s, came here, and did not contextualize himself as an Arab man. So I started doing research for that, including reading Mourid Barghouti’s memoir, “I Saw Ramallah,” which I think everyone should read. And then I wrote [“The Hour of Feeling,” the first act of The Vagrant Trilogy].

You just mentioned how your father did — or didn’t — contextualize himself after arriving in the United States, and that made me think about how Adham walked the same line in England as a Palestinian, because it’s clear Adham doesn’t quite know where to position himself on that axis of being in exile versus in the diaspora. Did you ever get a sense of where your father landed on that point?

He did not contextualize himself in the sense of having pride in his Arabness. He was rather pro-West and very interested in and invested in the American project — we’ve had arguments about [Gamal Abdel] Nasser, for example — and at the same time he had this very villager-y life: people popping over with no notice, his garden with the za’atar plant from his village…

Adham, I think, is rather complicated. He is sent out into the world by a woman [his mother, Beder] who has been traumatized by war and displacement. She’s left her husband and other son in a refugee camp and taken her younger son away, back to a different part of Palestine — they’re from the Galilee, and end up going back to the West Bank. When Adham is pushed [by Abir] at the end of the first play [to prove he loves her], he isn’t wrong about [Beder] when he says, “she taught me how to love this way,” because there wasn’t anything in her life that wasn’t taken away from her.

If I had to encapsulate my own feelings about the whole notion of displacement, it would probably be in that line. The psychic effects of displacement have always been compelling to me, along with the idea that you’re not of the place you left or were forced out of, and you won’t be of the place you’ve gone to either — and the generational trauma that occurs.

The play seems to really grapple with the idea that once you emigrate, or you’ve had to flee or have been forced out, you can never really go home again, even if you physically return to the place you came from: as you’ve said, you’re not the person you were when you left, and the place you left has changed in the meantime as well. With Adham, we see that playing out literally and metaphorically across the three plays. Why was it so important for you to put this aspect of displacement front and center?

It was a way for me to approach the heartbreak of Palestinian existence, around the notion of displacement. I was able to connect with it through drama. I had a very clear idea of what Adham’s apartment [in London] should look like in the middle play: when my cousins came over [to the United States from Lebanon] and got apartments, there was nothing on the walls, and they’d have just a few things they’d brought. There was something about the objects that spoke to me.

And so the only thing on the wall of Adham’s apartment was a tatreez, Palestinian embroidery, and that tells a story of his conflicting impulses. He is not reconciled with his own trauma; he has not reconciled his leaving with the choice he made in 1967.

His wife [who has returned to London in the second play], on the other hand, has. She knows she will never be “of London,” but she allows herself to face, on a psychic level, the damage. But they’re both reckoning with the fact that there’s no going back.

I grew up around quite a few people who left a place, and then saw in the rearview mirror that the explosions continued. And with that there’s an issue of survivor’s guilt.

The play opened a month or so after Russia invaded Ukraine, amid a full-throated public conversation about refugees — and who people see as a “desirable” or “legitimate” refugee. Did that change how you thought about the ways in which audiences might receive or react to the play? Or about how the play’s message might resonate more broadly in this moment?

It didn’t. People have said [the play] is so timely because of Ukraine, which is fair, but sadly for those of us who watch the Middle East it’s almost never not timely. What shaped the play more was the two-year [pandemic-induced] delay, and the horror show of living with this uncertainty, ambiguous loss, separation, and isolation.

But the play does have a prologue now that it didn’t have before, and that came from wanting to say, “here’s everybody, here are the people that are going to be [acting] in this,” and all of them are people who’ve either left their homeland, or whose parents were forced out or left. [Every cast member is of Middle Eastern descent — NRR.] And you’re seeing them all [as they are] in the beginning, because half of them are about to play white people.

[The prologue] was a stand-in for what I had originally wanted, which was [passing around] food. I wanted to be disarming at the top of a play about the Middle East, about Palestine, where even someone who’s supportive of Palestinian rights might think, “OK, I’d better hunker down here, I’d better stay sharp and serious.” Even pre-COVID we couldn’t do food, so we did this welcome instead.

Because I never stop thinking about this stuff, I don’t take into account that other people do. I knew refugees from the age of 8, 9, 10, because my cousins were fleeing a war. That can look many different ways, and we tend to think that once you’ve left it’s a straight line, but it’s not. I had an uncle who would go back and forth during the peak of the war. What compels you to do that? That’s the stuff that’s interesting to me as a dramatist. And if people are getting this more because of [Ukraine], great. But I don’t think that I or anyone else in the play has ever needed an access point to these Palestinian characters.

You mentioned disarming people ahead of presenting them with this heavy history, and something that really stood out is the progression in how the Nakba is addressed throughout. In the first play, it’s mostly referenced in the form of witty asides, which by the end of the final play make way for a very direct and agonizing confrontation with the ongoing reality of Palestinian displacement and exile. Can you unpack that arc?

It was partly by accident — we could have done the plays in a different order — but the way it functions is that by the third play, there’s nowhere left for Adham to go. The third play is a living room drama, and it’s the only room. There are no decorative light cubes or videos like you have in the first two plays. And it’s in the third play that Adham’s daughter, who functions as he did in the first play [in wanting to leave], forces him to reckon with what has been lost: this dream of ownership of land, which is encapsulated in Wordsworth who, as a romantic poet, walks and walks.

The Palestine that Adham is part of in 1967 is regulated, and there are places that are off-limits to him. I love the fact that he doesn’t know himself fully — he doesn’t know why [Wordsworth] speaks to his existence, that there’s almost this wish fulfillment [in terms of being able to walk the land]. And there are other places in the world where that kind of walking is not possible, but there’s no place I can think of where so much is off-limits as Israel-Palestine.

Also, by the time you get to the third play, all these Middle Eastern actors are playing Middle Eastern characters. There are three folks of Palestinian heritage in the ensemble, and I don’t want to speak for them, but I think that while it resonates deeply for all of us, it’s extra [resonant] for people who are playing things out that are happening to their families right now, or that happened in ’48.

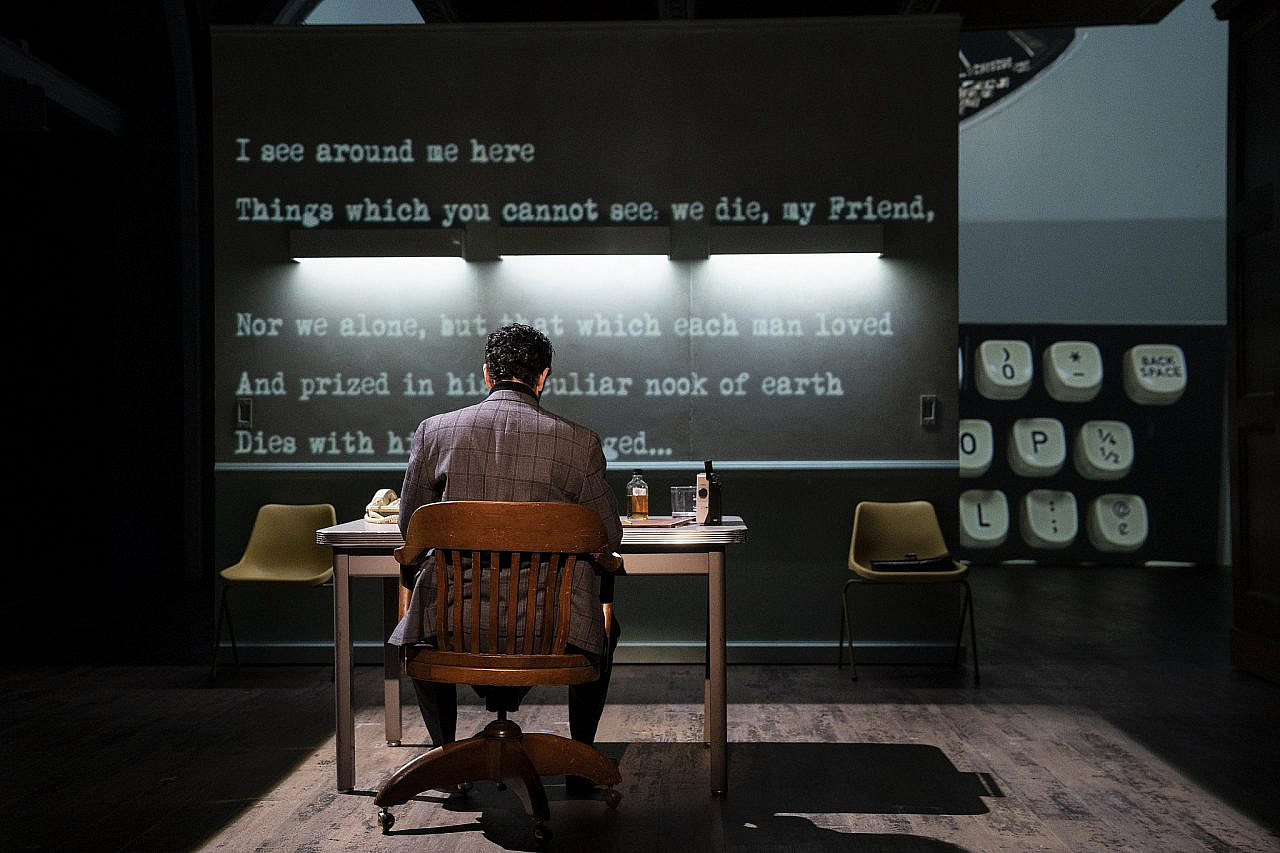

written by Mona Mansour and directed by Mark Wing-Davey, at The Public Theater, March 8, 2022. (Joan Marcus)

Your point about walking and ownership of the land — and how that was off-limits to Adham in Palestine — makes me think of how in the early years of the Israeli state, that was a key way Israelis rooted themselves in their new country. They would walk across the land as a way of familiarizing themselves with it, and, in so doing, claim ownership of it. So what you’re saying about Adham is a powerful juxtaposition.

Right, and it’s just like Raja Shehadeh’s gorgeous book “Palestinian Walks”: who doesn’t want to walk around their land? In that sense, my father was a man of his part of the world as well. We grew up in southern California and he would walk, grab something off a tree, put it in his mouth, and that was his childhood. There are still olive trees in his village — his family were farmers, so I feel a tie to that.

There’s a line from one of Wordsworth’s poems, “The picture of the mind revives again,” that is spoken by different characters in each act [the line is from the poem “A Few Lines Written Above Tintern Abbey,” in which Wordsworth reflects on returning to a place he’d visited a few years earlier, and how his memories of it had shaped him in the interim, even as he’d been separated from that landscape]. What is the significance of that line to you, in reading it for the first time and in the context of the story you’re telling with this play?

It’s that whole notion of an imprint. There was a double-edged sword to the idea of an imprint for Wordsworth: because he returns, it solidifies this imprint, which means he can go anywhere and this place will stay with him. But the sad side of it is that he might have less of a need to be [physically] in that place himself.

It’s a convenient philosophy for Adham to subscribe to, because I think he’s an exile from himself. He tells himself he doesn’t need to be in Palestine, he doesn’t need to be with his mother — his mother is a stand-in for Palestine — because she’s here [points to head] and here [points to heart]. This is a man who’s not conscious of what it is he’s missed and is missing.

I just had a conversation with my dad about this. My sister was reading him part of the New Yorker article that was just published about the show which talks about him leaving [Lebanon], and my dad interrupted: “I couldn’t wait [to leave]!” Then my sister reached the line where I say I don’t believe him when he says he doesn’t miss it, and she asked him, “Do you miss it?” And he said, “Well, you know, my parents, sometimes,” who’ve both long been dead. And that duality is what speaks to me — when people, to move forward, somehow turn their back on a place. It does break you in some way.

I met my own grandparents only once, because of war. I met them as a very little girl and then never again. It’s heartbreaking when I stop and think about it. So the only way I know to try and be human is to write into that, and I named the character Beder after my own grandmother as a way of honoring her.

After extending its run, The Vagrant Trilogy had its final performance at The Public Theater on May 15. What’s next for the play, and for you?

We are all dreaming of this production transferring to the U.K., or Dublin. I’m working on a TV show called New Amsterdam, a medical show set in New York with a very kind writers’ room. I have a play running in Oregon right now called Unseen, which goes into production next year at Mosaic [in Washington, D.C.]. And my theater company has a play this summer in New York called The Beginning Days of True Jubilation, about a start-up, which is fun and sprawling and silly. That’ll be a nice change of pace.