From accepting a state on 22 percent of Mandate Palestine to Israel’s facts-on-the-ground in the West bank and the loss of rights for refugees, Palestinians have already made significant, historic compromises.

By Willem Aldershoff and Jaap Hamburger

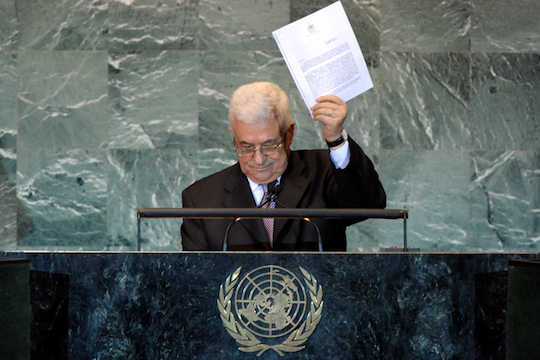

Despite the U.S.’s optimism, recent comments and statements coming from Israel and Palestine indicate that the U.S.-led Israeli-Palestinian negotiations are not progressing well. This is not only due to the relative complexity of the subject matter at hand, but first and foremost, due to the fact that the Palestinians and Israel differ greatly in power and position: one being the occupied, the other the occupier that maintains an “unbreakable bond” with the world’s only military superpower. Americans and Europeans do not tire of insisting that only “painful concessions” by both sides can make a just and lasting agreement possible. The central question is; what additional concessions can, or should the Palestinians still make without undermining the very idea of a two-state solution?

The territory of Israel already covers 78 percent of the former Palestine Mandate: this is almost 50 percent more than what the 1947 UN partition resolution recommended, which allocated 55 percent of the land to the Jews. Even under the most optimistic scenarios nowadays, a Palestinian state will never comprise more than 22 percent of Mandate Palestine. Accepting this unequal distribution is by far the greatest Palestinian concession, made by late PLO-leader Yasser Arafat when he formally agreed to a two-state solution in 1988.

Read +972’s full coverage of the peace process

As a condition for admission to the UN in 1949, Israel accepted UN Resolution 194, which stipulates that Palestinians who fled or were expelled during the Jewish-Arab hostilities of 1947-49, have the right of return. Israel has not respected this obligation. On the contrary, after its unilateral declaration of independence in 1948 Israel began destroying hundreds of deserted Palestinian villages in order to prevent the refugees from returning and confiscated the land they left behind, without compensation. The chance that large numbers of Palestinians will be allowed to return under a future two-state deal is nil. That is the second – forced – “concession” from the Palestinian side.

A third “concession” imposed on the Palestinians concerns their land on which Israel has been building settlements since 1967, in clear violation of international law. More than 500,000 Israeli settlers currently live in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem. Israel appears to take it for granted that the international community and the Palestinians should just accept that these facts-on-the-ground will, “unfortunately,” not be undone. Palestinians should be grateful that they will even be compensated with “comparable” areas of Israeli territory, according to Israel.

A fourth forced “concession” concerns Jerusalem, which according to the UN, should have been placed under international administration. During the 1967 war Israel annexed the Eastern part of the city. The UN Security Council, the International Court of Justice and the entire international community, including the U.S. and EU, have repeatedly stressed that this annexation violates international law, refusing to recognize its legitimacy or legality. Nonetheless, Israel encourages its nationals to move to East Jerusalem and pushes out Palestinian residents, all the while destroying their homes and community buildings and refusing to grant them building permits. Thus it is a virtual fait accompli that a future Palestinian state will not have the whole of East Jerusalem as its capital.

Next, it is self-evident that a fundamental condition for the viability of a Palestinian state requires that it be geographically contiguous. This is only possible through a physical connection (corridor) between the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, currently separated by Israeli territory. Oslo II already provided for safe passage arrangements between the two territories. Therefore, this should not be a subject for endless negotiations. Also here, however, Israel will undoubtedly demand a price for this corridor, consisting of compensation in land.

A final point concerns the security of Israel and for the Palestinian state. Israel understandably demands guarantees for its security. Yet the question remains: what is reasonably required to achieve this? Israel insists that Palestine must become fully demilitarized, that its air force be allowed unrestricted use of Palestinian airspace and that its army maintain a presence in the Jordan Valley. Such conditions would be unacceptable for any independent state. Furthermore, the Palestinian state is no less entitled to security, such as guarantees that a heavily armed neighbor does not barge in whenever it pleases.

All this illustrates the impossible situation in which Palestinian negotiators find themselves. They must defend the interests of a small people, occupied for almost 50 years by a state with one of the strongest armies in the world and that enjoys the unconditional support of the only remaining military superpower. How can Palestinians under such conditions ensure that a final peace agreement leaves them with the very minimum to which they are entitled? Such an outcome can only be possible if a truly “honest broker,” for whom international law means something, mediates between the parties.

Despite its ambitions, the United States cannot play this role. Past experience shows that its “unbreakable bond” with Israel, of which it prides itself, causes the U.S. to give preference to Israeli interests at decisive moments. One need only listen to this week’s speeches at the annual AIPAC conference to hear the depth of the relationship in Israeli and American policymakers’ own words.

It is clear that the European Union urgently needs to actively commit itself to a solution that is acceptable to the Palestinians and not only for Israel. That means an agreement that gives them the bare minimum to which they are entitled: not one square meter less than 22 percent of the original Palestine, the entirety of East Jerusalem as their capital, a corridor between Gaza and the West Bank and a just solution to the refugee problem.

Israel must not be allowed to spin respect for international law and its existing commitments as a “concession”; that is the minimum it is obliged to do.

Willem Aldershoff is an adviser of EU-policy on Israel/Palestine in Brussels and Jaap Hamburger is the chairman of “A Different Jewish Voice” in Amsterdam.

Related:

Why the two-state solution needn’t stay that way

Good news: Obama gives the Palestinians an insurance policy