The period of Israel’s history that by far saw the largest economic growth, more than any other, was the six years following the Six Day War. And what agricultural, industrial, or hi-tech breakthroughs took place around 1967-1973? None worthy of mention. More than any other single factor, it was the establishment of the Occupation-Settlement Enterprise.

By Dr. Assaf Oron

This week, Dr. Karnit Flug became the first woman in Israeli history to be appointed Governor of the Israel Central Bank – a position analogous to the U.S. Federal Reserve chair. The process leading up to her appointment played out as a satirical mirror-image to what had transpired in America a short while earlier.

In both cases, the outgoing chair/governor had strongly recommended his second-in-command, a woman, as successor. In both cases, the government had originally skipped over the female candidate, instead courting has-been male candidates with skeletons in their closets. And in both cases, common sense eventually prevailed.

There were, however, the familiar differences between the American process and its Israeli doppleganger, in the depth of the farce. Whereas the Obama administration had only considered Larry Summers over Janet Yellen, but never formally extended the invitation – the Netanyahu government managed to formally appoint not one, but two would-be male governors, only to see both candidacies evaporate into thin air. Then, Bibi and his finance minister, Lapid, bickered and vacillated over various other candidates for an additional three to four months before finally reverting to Flug – who was meanwhile the acting governor – as the option of last resort. This was preceded by Lapid – a few months ago Israel’s rising political star and nowadays its favorite laughingstock – going on national TV a mere four days before the final appointment and stating in his signature dismissive overconfidence that, “Flug will never be Bank of Israel governor.”

But without a doubt, the cherry on top is the reports from multiple sources that at the very last moment, Netanyahu extended a desperate invitation to none other than Larry Summers himself. That’s how I learned that Summers is Jewish. In Netanyahu’s world, any male neoliberal economist of Jewish descent, anywhere on the globe, is a more appropriate Bank of Israel governor than an Israeli-born woman who rose through the Bank’s ranks (Flug’s predecessor was American Stanley Fischer).

But I digress… sorry, Israeli politics are often so funny that no satire can do them justice.

Why this virulent “Anti-Flugism” on Netayahu’s part? What is, metaphorically, the “dark secret” that made Bibi try to throw everyone and the kitchen sink into the Governor position, just to avoid the natural successor?

Flug’s lack of a Y chromosome does not explain the depth of Bibi’s hostility. Instead, most economic journalists point towards a working paper published in 2007, when Dr. Flug was head of the Bank’s research division.

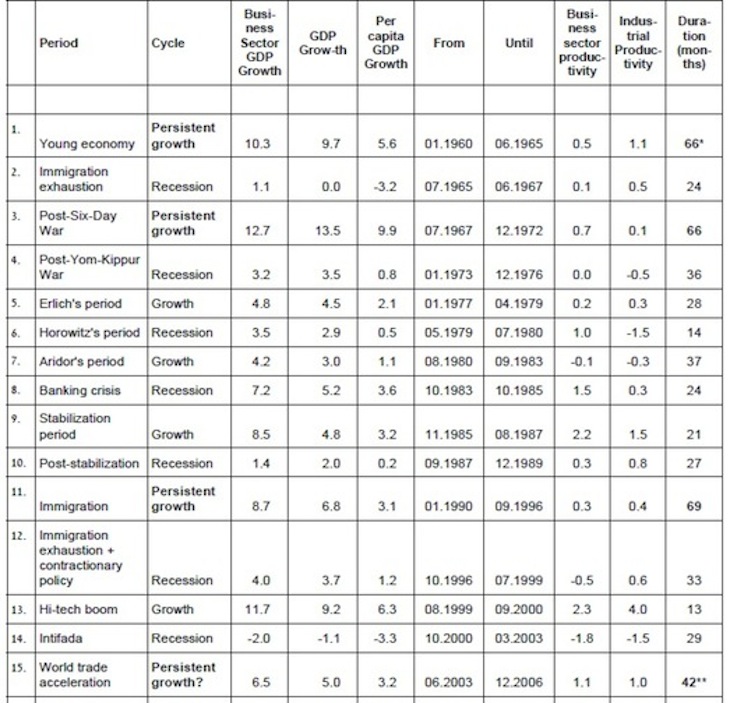

That paper, co-authored by Flug and Dr. Michel Strawczynski, divided Israeli history from 1960 through 2006 into periods delineated by historical and economic turning points, and calculated the growth in each period as well as a host of variables representing economic policy and the political situation, in an attempt to answer the question: what are the main drivers of growth periods? More specifically, do these tend to be geopolitical factors (wars, immigration waves, the global economy, etc.) – or the Israeli Treasury’s macro-economic policy (deficit, liberalization, public investment, etc.)? Here is the raw data from the article:

Flug and Strawczynski concluded unequivocally that during the period they studied, geopolitics had trumped economic policy in their impact upon Israel’s economic fortunes by a 2:1 ratio. Frankly, no elaborate econometric models are needed to draw that conclusion: the table shows it directly, and anyone with a living memory of a substantial chunk of that period can attest to that. If anything, the models might have granted economic policy more than its fair share, at the very least due to the fallacy that macro-economic steps have an immediate effect rather than a delayed one.

Anyway, the Flug-Strawczynski report was a thorn in Netanyahu’s side. In 2003-2006 he had clawed his way back from the political wilderness and as finance minister, implemented a radical neoliberal agenda of brutal social safety-net cuts and rampant privatization. That period coincided with Israel’s emergence from its deepest economic crisis since the 1970s – the Al-Aqsa Intifada crisis of 2001-2003, exacerbated by the 9/11 recession.

Bibi has presented Israel’s recovery from the 2001-2003 crisis as evidence of his economic genius, and as his claim to gravitas in the eyes of Israel’s socio-economic elites, who had up until then seen him as a superficial hack. Yet, here comes the head of the central bank’s research department, who states in a formal report that in reality, Israel’s economy mostly rode on George W. Bush’s coattails to exit the crisis.

Fair enough. That probably explains Flug’s “Dark Secret” vis-a-vis Netanyahu. It is a bit ironic, because the report authors actually go out of their way to praise Bibi’s economic policies, to an almost embarrassing degree considering this is was a research report and not an op-ed. Yet they could not undo their results, and could not allay Bib’s wrath.

But this tempest in an economic teapot is not the Dark Secret I care about.

I was very glad to discover the Flug-Strawczynski report. Not because of the analysis – I am not a fan of neoliberal models; they seem to be “flexible” enough to give neoliberals exactly what they want, reality be damned. Thomas Herndon brilliantly showed this about the influential Reinhart-Rogoff article; I had my own, eerily similar personal experience with this type of (mal)practice by another celebrity neoliberal, Dartmouth’s Jonathan Zinman. In the Flug-Strawczynski case, the signal coming from reality was probably way too strong to be obliterated via neoliberal hocus-pocus modeling.

No, it was not the analysis I was glad to see. It was the raw data in their Table 1 shown above. The data exposes a dark secret that is not Flug’s – but rather, shared across the entire Israeli elite. In fact, it is a secret hiding in plain sight.

How Did Israel Become a Wealthy Country?

In the last 30-40 years or so, Israel has been a Westernized country, wealthy relative to most of the world – both in terms of lifestyle and in terms of self-image. That is, most Israeli citizens nowadays both live a Westernized, consumerist, relatively wealthy lifestyle, and expect to deserve this kind of life. Most current international economic indices of wealth show Israel in the top 10-15 percent of countries worldwide.

In 1960, the beginning of the period examined by the Flug-Strawczynski report, this was not the case, not at all. So what triggered Israel’s “economic miracle,” its transition into a solid First World status?

If one compares Israel to other countries that hop-skipped from the “Second” or “Third World” to the “First World” over a similar time frame, the question’s difficulty becomes more apparent. In the Israeli press there have been attempts to cast Israel as an “Asian Tiger” like Japan, South Korea, or Taiwan. But all these Tigers took a pretty clear path to prosperity: they became global industrial export powers. Israel, too, takes pride in its exports; but our exports have never reached “Tiger” levels and have never exceeded our imports (under certain calculation choices, in 2010 Israel’s exports briefly and narrowly exceeded its imports – but not when all imports and exports are considered; and even this hasn’t happened in any other year).

So Israel is not an “Asian Tiger.”

Some European nations, too, have emerged from relative poverty to relative wealth over a similar period: Italy and Spain come to mind. During their period of rapid growth, these countries enjoyed stable peace, maintained very small militaries, became global tourism magnets – and, to boot, had positive foreign-trade balances for most of the time. Israel certainly did not follow this path either.

So what is Israel’s secret?

The common Israeli answer to the riddle is a mix of self-congratulatory theories. The most popular is a story of generational brilliance: it begins from our amazing agriculture built from the 1930s to the 1960s (only to be dismantled later by neoliberalism), followed by amazing “traditional” industry from the 1950s onwards (which, again, produced far less exports than our imports at any given point in time, and has been largely dismantled since the 1980s) – and nowadays, the fabled “Silicon Wadi”, the golden calf of Israeli hi-tech.

Another explanation comes from Israeli fans of neoliberalism. After long years of quasi-socialist or inconsistent policies, sometime in the mid-1980s Israel’s macro-economic policy started following neoliberal dogma. Since then, its neoliberal marks only keep improving. This – according to neoliberals – is the source of economic manna raining on Israeli heads. This latter theory is the one examined by the report. The authors’ models managed to rule a respectable defeat: neoliberal orthodoxy was not a decisive factor in Israel’s economic growth, but it was “statistically significant” (as a statistician I question the “significance” premise here, for various reasons).

But the raw data alone suffices to show that the “neoliberalism brought us prosperity” theory is pure hogwash. If it were true, we’d expect the numbers in Table 1 to show weak or inconsistent growth before the late 1980s, and ever-accelerating growth since then. What we see instead is perennial inconsistency, start to finish – but with the longest periods of strongest growth happening predominantly in the 1960s and 1970s, well before the advent of Israeli neoliberalism. Don’t believe me? Here’s what the authors themselves write: “After 1973, growth periods were scarce and short…” (p. 5).

So neoliberalism is not it.

What about the agriculture-industry-hi-tech explanation? The real data is not kind to them either. What was the most massive persistent-growth period, far ahead of any other period in 1960-2006? The six years immediately after the 1967 war. Per-capita annual growth during these six years was an astronomical 9.9 percent, with the short Intel-led “hi-tech” burst of 1999-2000 coming in a distant second at 6.3 percent, and 1960-1965 third with 5.6 percent (Table 1, third column of numbers). Not only was the 1967-1973 growth rate phenomenal; this period is also one of the longest in the hectic history depicted in the table (and for unknown reasons, the authors wrongly snip it somewhat too short at December 1972, instead of September 1973 on the eve of the 1973 war). Cumulatively, over the 76 months from the 1967 war to the 1973 war, Israel’s per-capita GDP had almost doubled.

What agricultural, industrial, or hi-tech breakthroughs took place around 1967-1973? None worthy of mention. Rather, the project bringing about this growth spurt, the project most responsible for shifting Israel from “Second World” to “First World” economic status – not exclusively, but more than any other single factor – is the establishment of the occupation-settlement enterprise.

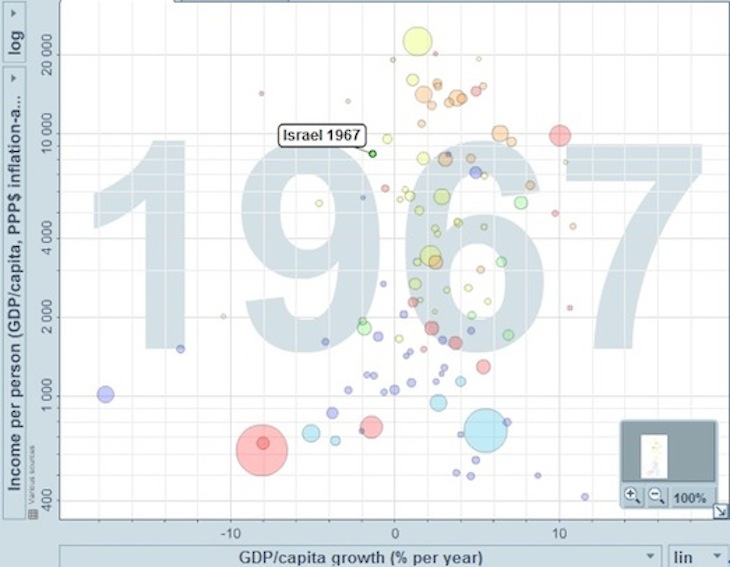

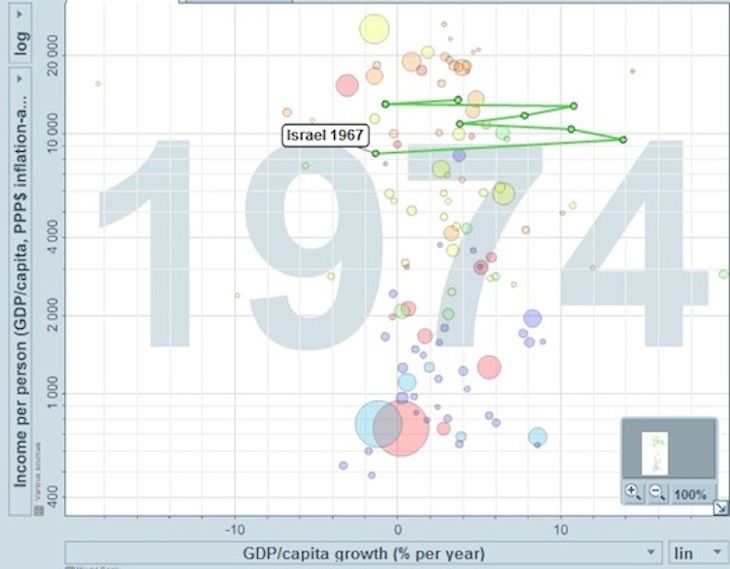

As I said, this is a secret hiding in plain sight. The data are public, but no one seems to be interested in them, and certainly no one in Israel cares to emphasize them. I first encountered them a few years ago, on the amazing global-health visualization website gapminder.org. Playing with the interactive graphs there, I was naturally curious about my home country.

Below are some Gapminder plots highlighting Israel. The x-axis shows the current year’s per-capita growth rate, while the y-axis shows the (log-transformed) per-capita GDP. In the 1967 snapshot, Israel is near the top of the “Second World” cluster, not far from countries like Hungary and Yugoslavia. By the 1974 snapshot, it had already hop-skipped to the bottom of the “First World” cluster. The dots connected by a green line show Israel’s remarkable annual per-capita growth numbers during the intervening seven years. Making a similar leap concurrently with Israel are Japan (large red circle), Italy and Spain (somewhat smaller, orange circles).

So I’ve known about this data for a while. But Gapminder is “just a website,” and a European-based one to boot. Israelis have retreated since 2000 into a reflexive denial of any embarrassing information coming from abroad (even if the source is a likeable Swedish public-health professor dealing with 200 countries’ data and not obsessed with Israel in particular). Therefore I was really glad to see an official report from none other than the Israel Central Bank, admitting the same reality, black on white.

So what do Flug and Strawczynski have to say about the remarkable growth spurt of 1967-1973? Par for the Israeli establishment’s course, they say next to nothing about it. Yes, a 37-page report named ”Persistent Growth Episodes and Macroeconomic Policy Performance in Israel” devotes almost no attention to the single most massive growth period in its study. The only half-hearted reference to this period is in parentheses, saying that the 1967 war “(…enhanced growth since it was short and created prospects for improving Israel’s geopolitical situation)” while the 1973 war did roughly the opposite – and this too, was not invoked to explain growth, but only to explain why the authors didn’t include wars directly as a covariate in their model (p. 12; they did include the number of terror victims, though).

Just for completeness, I will address this half-hearted, not-quite-an-explanation explanation as well. Yes, 1967 established Israel as a regional power. But this geopolitical upgrade came at a direct geopolitical price: the Soviet bloc immediately cut off all ties with Israel, turning it into an explicit Cold War pawn for better or worse. The Arab economic boycott, in place since 1948 but rather toothless during its first two decades, began to intensify, reaching its peak after 1973. And from a strict security perspective, as recent analysts point out, 1967 actually harmed Israel’s deterrence potential: on the Egyptian front the war never really ended, devolving into a bloody four-year war of attrition. It is after 1967 that Palestinians make their appearance as an autonomous player, launching guerrilla and terror attacks, first from Jordan and Gaza, then from Lebanon and worldwide. By contrast, the years immediately before 1967 were among the calmest in Israeli history. So neither geopolitics per se nor the objective security situation were the economic ATM making Israel rapidly wealthier between the summer of 1967 and the fall 1973.

What was this ATM then? It was the establishment of the Occupation regime, which paid immediate dividends in multiple ways. Here are some of them:

Arab Labor, Part A – Practically overnight, Israel’s labor market was flooded by a huge number of low-cost, high-quality indigenous laborers. The product of Palestinian labor for Israeli businesses directly contributed to our national wealth. It took a while for the authorities to actually document and partially “rein in” this labor (in the sense of it being formally reported). But its extent was truly torrential: within a few years there were scarcely any Jewish-Israeli manual laborers anymore. In addition, the documented minority among Palestinian workers, numbering tens of thousands from the middle of the period onwards, paid Israeli income tax and the Israeli equivalent of Social Security, without receiving anything in return, thus giving a boost to Israel’s government budget, too (since 1994 this money was supposed to go to the Palestinian Authority; withholding it has become a national sport among Israeli politicians).

Arab Labor, Part B – Palestinian labor made it far easier for many in Israel’s working class to hop-skip overnight into the middle class as independent business owners. The Israeli construction worker became an independent contractor, with Palestinians doing the work. The auto mechanic became an auto-shop owner, and so forth. Anyone living in Israel during the 1970s and 1980s recalls the crocodile-teared public refrain about, “All workers are Arab” and “Jews don’t want to do the work anymore…” But in reality, most Israelis were busy laughing all the way to the bank.

Arab Labor, Part C – The lower cost and higher yield of Palestinian labor allowed Israeli consumers to enjoy cheaper products and services, especially if they went to the Territories to purchase them – which in 1967-1973 was considered a perfectly safe, almost daily activity. Inside Israel itself there was a construction boom, with large modern apartments becoming affordable. Many Israeli business owners kept prices the same or even raised them as demand increased, becoming wealthier faster due to the dramatically higher margins.

The Settlement Enterprise – Conventional wisdom attributes the massive expansion of Israeli settlements to the right-wing Likud governments starting in 1977. In reality, even before that the settlement project had transformed some regions beyond recognition, first and foremost “East Jerusalem” – the vast regions in the city’s north, northwest, east and south annexed in 1967 that are far larger than both pre-1967 parts put together. A conglomerate of Jewish mega-neighborhoods sprouted on those hilltops within a few years. The new land was “free,” i.e., forcibly confiscated from its Palestinian owners, and labor was cheap (see above…). By 1973, Jerusalem had already turned from a sleepy border town to a vibrant sprawling city, greatly invigorating the capital’s economy.

Captive Market – Overnight, the “domestic” market for Israeli products increased in the size of its population by some 50 percent. After taking over the Occupied Territories, Israel imposed a customs union on them and either completely blocked or placed strong barriers on imports into the Territories from abroad. Local Palestinian industry was also repressed by suffocating military bureaucracy, as well as by the situation itself. Gapminder.org pegs the per-capita Jordanian buying power in 1967 at roughly one-third of Israel’s; so depending upon product, the actual market expansion was probably smaller. But would any business complain about an immediate 10-20 percent market expansion? For Israeli monopolies the captive market was especially lucrative. For example, Israel’s three oil companies united to create “Pedesco,” a gas-station monopoly operating only in the Territories. But the jewel in the crown remains the currency monopoly. The Israeli lira (the shekel’s predecessor) became the Territories’ only de-facto currency, and Israeli banks charged Palestinian banks confiscatory fees for the privilege of using it.

An Arab Boycott bypass road – As written above, post-1967 Arab nations became gung-ho about boycotting Israel. However, the so-called “Open Bridges” policy announced by Israeli Defense Minister Moshe Dayan allowed West Bank businesses to export to the Arab world via Jordan, and the West Bank label was not boycotted. Israeli businesses quickly took advantage of this opportunity, and ever since 1967 a lot of Israeli products have been sold to unsuspecting Arab-world consumers under a false label, thus accessing previously unreachable markets. This was especially easy with agricultural produce. The Israeli press was openly bragging about the practice in the 1970s.

Exploitation of natural resources – Easiest to exploit was, of course, the land itself. But other resources have been intensively, and quickly exploited as well. Only years later, it was revealed that starting in summer 1967, Israel pumped massive amounts of oil from the Abu Rudeis field in Sinai; by 1973 this field supplied half of Israel’s oil consumption. In addition, water from the Golan Heights taken from Syria in 1967, doubtlessly helped Israeli agriculture in the North, the country’s most productive region (pre-1967, the incessant “water war” with Syria was the single greatest flashpoint along Israel’s borders).

Expansion of Government Spending – Many of the items above necessitated massive public spending. But more than all everything else combined, military expenses had mushroomed beyond belief. Huge new bases were built in the Territories, in Sinai above all – including the ill-fated Bar Lev Line fortifications. The number of employees in Israel’s “security industries” increased by 150 percent from 1967 to 1973 (h/t Shir Hever for the datum). This was yet another stimulus to Israel’s economy, and an increasing chunk of it came from the United States as military assistance (which was essentially nonexistent pre-1967). But some of this spending was unfunded; indeed, Israel’s budget dipped into the red in 1969, and by 1973 the government ran a hefty deficit.

“Start-Up Nation”? The most amazing start-up in Israeli history remains the establishment of the occupation regime. One teeny problem: we forgot to make our strategically timed exit.

Despite the remarkable commitment of most Israeli governments to the occupation and settlements, these twin projects have never again succeeded in delivering a boom remotely similar to 1967-1973. Even worse, the occupation has become the major instigator of Israel’s economic crises. This, of course, started right then in October 1973. The war’s direct cause was an Egyptian realization that Israel intends to make permanent its occupation of the Sinai. The 1973 war hurled Israel into one of its worst economic crises (slightly mitigated in Table 1’s numbers by the misguided addition of three pre-war quarters), a crisis with global implications due to the oil embargo it triggered. Thereafter, both Intifadas – Palestinian rebellions against the occupation – had also triggered recessions, with the 2001-2003 recession’s numbers being the worst in the study period.

Emerging from the mid-1970s crisis and the late-1980s crisis required that Israel pay a political price. On the first occasion, it was returning the Sinai and (falsely) committing to Palestinian autonomy. On the second occasion the price was engaging in direct negotiations with the Palestinians, leading to some limited autonomy. But the exit from the 2001-2003 crisis was granted to us by the George W. Bush administration free of charge, as part of his crusade to reshape the Middle East, and of his generally superb skills in running things.

This unbelievable (and highly irresponsible) politico-economic gift from Bush has caused most Israelis to enter a mental bubble of smugness and disengagement from reality. It is this bubble that explains much of Israel’s ridiculous military adventurism since the mid-2000s. It is this bubble that allows Bibi to boast of “saving Israel’s economy” via some neoliberal magic potion. And it is this bubble, in which economists like Flug and Strawczynski attempt to “investigate,” supposedly, what causes Israel’s growth and recession cycles – all the while completely ignoring the occupation regime that actually underlies most of them.

If you are still confused as to what this little post’s message is:

Post-1967, Israel’s economy became an occupation economy first and foremost. Setting up the occupation regime gave us our biggest economic growth spurt. Since then, the occupation’s woes have given us our worst crises.

Yes, there is also Israeli hi-tech, and there is also macro-economic policy. But studying Israel’s macro-economy without explicitly entering the occupation regime into the picture, is – my apologies if this offends anyone – tantamount to economic malpractice.

On an overall calculation, my guess is that Israel is still somewhat ahead, economically, on the cumulative gains and losses from its occupation gamble. This is mostly at the expense of Palestinians, of course, but also increasingly at the expense of the U.S., the EU and others who have poured increasing amounts of money and effort to keep the situation in Israel-Palestine from falling completely off a cliff. That inflow of outside money has helped us retain many of the occupation’s benefits (for example, at least the Arab labor part was a massive growth and wealth-generation engine until 1987, rather than ending in 1973), while externalizing the humungous military cost, and shirking responsibility for crippling of Palestinian economy. Yet, the occupation’s annual balance is probably negative nowadays, and getting worse, on average, every year.

So why can’t we give it up? Besides the well-known political and social reasons (fear of Palestinians in general and terror in particular, the settler Right’s chokehold on national politics, plain inertia), there is also the memory of the original “high” of 1967-1973. That initial boom still lives in too many Israeli hearts and minds, equating the occupation and “greater Israel” with a sense of prosperity. That explains our collective behavior patterns, such as,

• Pledging to give up the occupation again and again, yet not following up, and very often not even doing anything that can realistically lead to its end;

• Denying or suppressing the occupation’s existence, its nature or the magnitude of its impact upon Israeli life;

• Blaming everyone but ourselves for its side effects.

In short, the classic behavioral patterns of an addict.

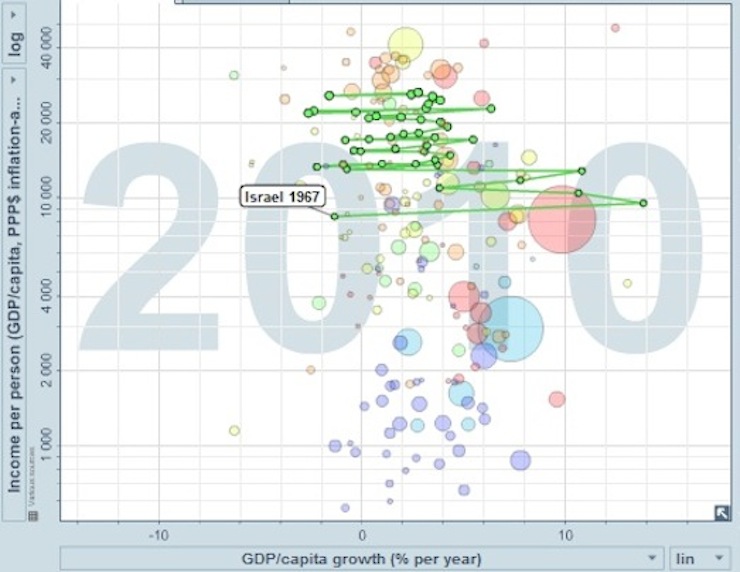

Whoever is still not convinced how unique 1967-1973 were in Israeli economic history, here is a gapminder.org trace of Israel’s annual growth rate from 1967 through 2010. No other period comes close.

A few notes from the discussion that followed the Hebrew version:

The fact that the occupation’s start-up period made Israelis much wealthier, on average, does not automatically mean that it made Palestinians poorer during that same time. Rather, the effect on Palestinians seems to had been mixed: many of the elites suffered (exiled, jailed or lost a lot business-wise); new elites – those who knew how to do business with the occupation – gained; and the common Palestinians often made more money from serving the new masters’ needs. However, medium and long-term the switch from a mixed farming/urban, developing economy towards a predominantly day-labor based one, has not been good. Infrastructure and skill development stagnated, and Palestinian income became almost entirely dependent upon the whims of Israel’s policy toward Palestinian labor.

There is no denying that Israeli hi-tech has been an important growth engine. However, our hi-tech, which started in earnest during the mid-1980s and matured during the 1990s, is taking place against the background of an already wealthy economy. Therefore it cannot explain the critical transition into that situation. Moreover, major occupation crises, when they occur, still trump Israeli hi-tech together with the entire economy. In fact, one can see the last few years in Israeli politics and economics, as a frantic collective attempt to insulate the hi-tech and other ultramodern “First World” features from the occupation – without letting go of the occupation itself. This acrobatic effort is symbolized by one man: Naftali Bennett, a hi-tech millionaire who went on to become chairman of the Settler Council, leader of the settler-affiliated political party, and now serves as Israel’s minister of the economy.

Dr. Assaf Oron is an expatriate Israeli living in Seattle since late 2002. He works as a research statistician at Seattle Children’s Hospital. Prior to arriving in Seattle, he was active in the Israeli anti-Occupation groups Ta’ayush and “Courage To Refuse.” He now supports the activities of the humanitarian organization Villages Group from afar (http://villagesgroup.wordpress.com).

Author’s note: This is an English translation, with some updates and revisions by the author, of a text appearing in Hebrew on Haokets in September. My best wishes to Dr. Flug for her recent historic appointment. At this juncture I wouldn’t wish her new job on my worst enemy, but on a personal level the honor itself is well-earned. Contrary to what my introduction might suggest, as far as I know Dr. Flug’s personal credentials are impeccable. The “Dark Secret” is in fact shared by Israel’s entire economic elite. The title is attributed to Flug since her research work had brushed perilously close to that “Dark Secret” without exposing it. Thanks to Shir Hever for some information and for pre-publication comments. Thanks to post-publication talkback commenters, even the not-so-friendly ones, for helping me improve the English version.