They serve as Netanyahu’s echo chamber, they divert attention from the real issues at hand and they disguise political desperation as internet-activism. Memes shouldn’t be more than inside jokes, but nowadays they seem to lead the conversation.

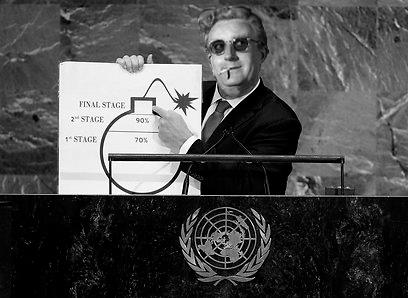

On Thursday night, Ami Kaufman posted on this site a collection of memes dealing with the Looney Toons bomb Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu used during his UN speech. Posted before any other local or international news source, it was one of the most successful items our site ever had (over 3,000 likes and counting). But did these memes aid the public debate, or truly criticize Netanyahu? I am not so sure.

Memes are part of a culture of irony, which has become the dominant approach to politics in certain circles – especially certain liberal circles. In the past, we used to lack irony in politics. People treated their leaders with too much respect, or took them too seriously. Now, it seems that we don’t take our leaders seriously enough.

Netanyahu’s UN speech is a good example: its topic was the prospect of a nuclear arms race in the Middle East, and perhaps even a nuclear war. There probably isn’t a more “serious” problem today. You need not agree with Netanyahu’s politics in order to acknowledge the gravity of the issue at hand; if you believe Iran poses an immediate existential threat to millions of Israelis, you must be anxious and tense as you watch this speech. If you feel – like me – that Netanyahu is creating an unnecessary escalation that could draw the entire region into war, and that his true aim is to divert attention from inner problems and the Palestinian issue, than the prime minister’s rhetoric can make you angry or sad.

Israelis watching this speech could feel either that their fate is in the right hands, or that a madman has taken over the throne. Their reaction to the speech could be hopeful or sad, admiring or upset – each of those reactions make sense. Each reaction, except for the sort of self-satisfied giggles that memes produce – the kind which seem to dominate the responses in the Left following Netanyahu’s speech. The aforementioned feelings could lead to political action. Giggling, like one would over pictures of babies and cats, can only generate “likes.”

In the past few months, I have been troubled by the prospect of war (“terrified” would be a more appropriate term) to the point of actually planning the evacuation of my family from Tel Aviv, in the event something does happen. I remember the missiles falling on Tel Aviv in 1991, and the thought of going through this with a child can literally keep us awake at night. Memes offer relief. They generate a feeling that “things are not that bad.” After all, we are only dealing with Road Runner bombs here.

I guess that this is a reason for the success of the ironic approach. Throughout history, irony has been a tool that has helped people deal with tragedies. But there is an important difference here: the Bibi memes do not deal with a past catastrophe but with a future one. Tragedy is a literary genre in which disaster is inevitable, while politics are about changing the future.

For me, memes represent desperation – a feeling that a catastrophe is around the corner and we cannot do anything about it. This is probably the worst approach to politics; the opposite of the existentialist notion that even when there is truly no hope, we should act as if there is one. And to be sure, I don’t think we are at a hopeless moment in history, not even in Israeli or Palestinian history.

On top of everything, those memes obviously help Netanyahu (not unlike the way Jon Stewart is helping Michele Bachmann). They serve as an echo chamber for the prime minister’s talking points. Take another look at those memes and you will find that some of them actually compliment Netanyahu.

Let’s think about it this way: if Netanyahu had a group of cartoonists sit in a room after his speech and asked them to produce highly viral content, I guess they could have come up with some of the same results as the leftists on my Facebook feed did. We feel those memes are critical because we place them in a critical context to begin with. Yet more often than not, they make everything seem playful and harmless; at other times, they increase the celebrity status of Netanyahu while avoiding a meaningful challenge to his politics.

Watch for example the “28 standing ovations” remix we posted here following Netanyahu’s speech in front of a joint session of Congress. At the time, it looked satirical. Now try to imagine this was a clip produced by the Prime Minister’s Office. Could it still make sense? I certainly think so.

It seems that sophisticated leaders like Netanyahu are by now well aware of the ironic approach to politics and are using it to their benefit.

On Thursday, as Netanyahu was preparing for “the speech of his life” (“his eighth,” noted a commentator on Israeli television), proxies to the prime minister hinted that the speech would contain a certain “surprise.” In the past, this kind of leak was meant to signal a political news item, perhaps a declaration of a new policy. But this surprise turned out to be a cartoon bomb. (Actually, the prime minister office couldn’t have been more literary, given the fact that most cartoon surprise “packages” contain bombs.)

Cartoons instead of policy – Netanyahu didn’t offer one idea or initiative since he agreed to utter the words “Palestinian state” somewhere in 2009. All he gave us were PR surprises, yet for the world media this is more than enough. The Israeli prime minister made the front page picture of all of America’s most serious papers on the day following his UN speech. I believe that the many editors who placed this front page picture found the cartoon bomb to be ridiculous and childish, but nevertheless, played along with the trick. (I remember similar dynamics in the media desks I have worked on.) As it is often the case with “progressives,” the ironic enjoyment of the moment overcame the editors’ political and professional judgment, to a point where playing along with the gimmick becomes the professional thing to do.

Even The New Yorker had its own highbrow version of the Bibi meme industry. Like others, the magazine’s editors preferred the performance to the content of Netanyahu’s speech. If Netanyahu was indeed trying to divert attention from the Palestinian issue, his worst critics were the first to play along. The ironic zeitgeist allowed for this.

At this point, it is clear that the brilliance of Netanyahu’s move was that the bomb was so lame. If he was quoting reports and scientific data on an actual nuclear bomb, or showing a proper diagram, he would not have gotten the same effect. In the end, the joke was on us.

Political powers, it is worth remembering, are never ironic. An amused approach to politics helps drive attention away from the true meaning or consequences of their actions.