Stuck in a Zionist paradigm, Israel’s mainstream left-wing parties are unable to put forth a vision of equality and inclusion for all in Israel-Palestine.

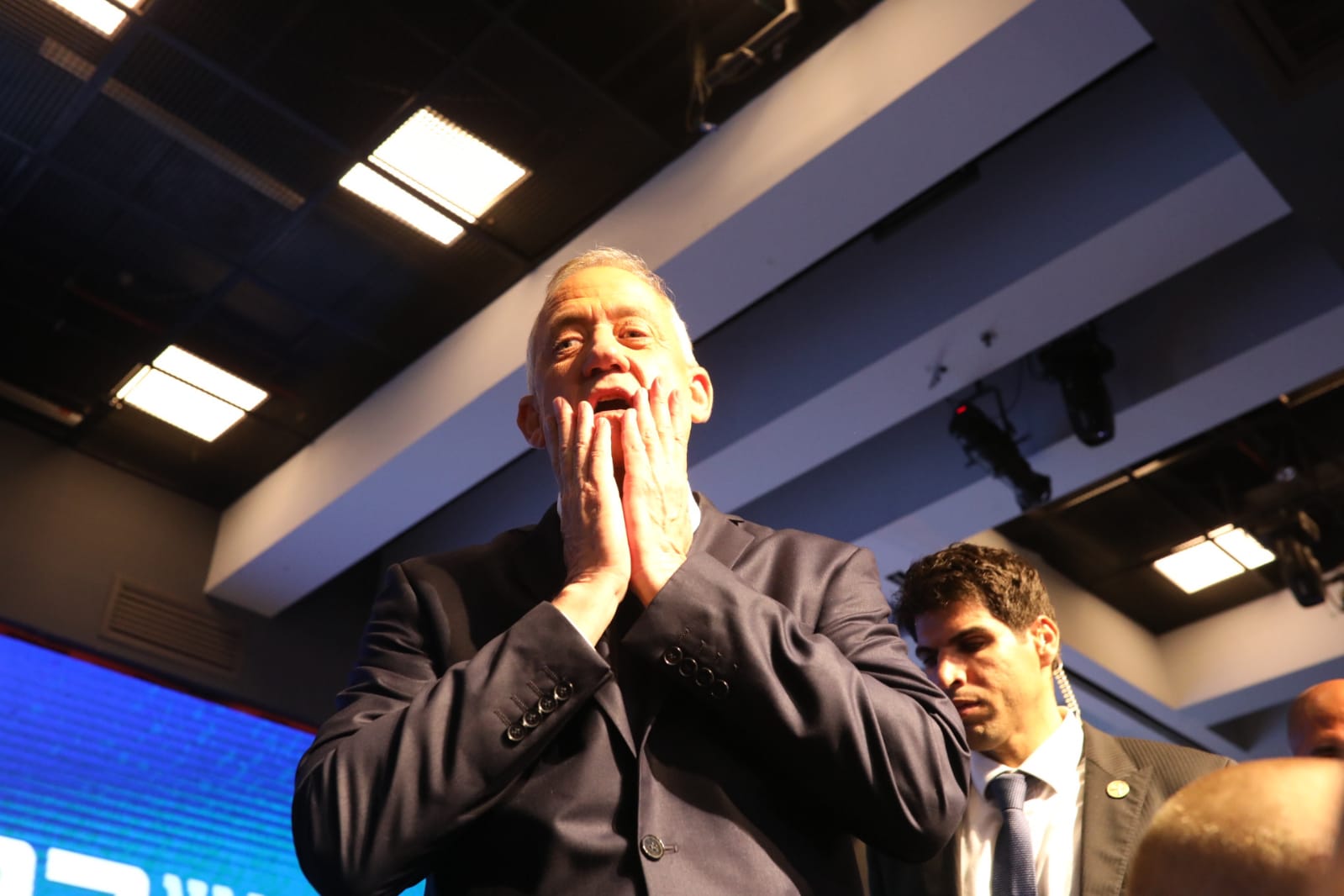

Tuesday’s election results were obvious to anyone paying attention. Although Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s Likud Party and rival Benny Gantz’s Blue and White won the same number of Knesset seats, Gantz has already conceded to Netanyahu, acknowledging that he does not have enough partners to form a governing coalition. Netanyahu will form a government with his “natural allies,” among them the far-right and ultra-Orthodox parties.

One of the most important stories that has been largely overlooked, however, is the spectacular implosion of the Zionist left. Tuesday’s election results, in which Labor plummeted to a record low of six seats, is as close as ever to a coup de grace. The Zionist Left, which includes the liberal Meretz party, is now reduced to just 10 seats in the 120-seat Knesset.

Labor and Meretz lost voters to Gantz’s “anyone but Bibi” campaign. But there is something far more fundamental at play here: neither party has been able to come up with a compelling vision because they are unable to grapple with two issues that haunt Israeli society: the dark legacy of 1948, and five decades of military rule in the occupied territories.

They are afraid because Netanyahu has shifted the discourse so far to the right that discussing the occupation has now become a taboo. Because those who want to talk about human rights violations in the West Bank or Gaza are now labeled traitors. Because talking about the Nakba or the fate of Palestinian refugees is beyond the pale.

There are, of course, other reasons for the downfall of the once-dominant liberal parties. For much of the past two decades, with the demise of the peace process that it once led, Labor has attempted to position itself as a centrist party with a dovish pedigree, abandoning left-wing politics altogether. While Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin reached out to Arab citizens in the early 90s — the Arab parties helped ensure he could push through the Oslo Accords while keeping his government intact — any talk of a real alliance with Israel’s Palestinian community has never been on the table.

Beset by years of accusations that it was too Ashkenazi-dominated, that it was corrupt, and that it did too little to undo the damage caused by institutionalized discrimination against Israel’s Mizrahi population during the early years of the state, Labor brought in Avi Gabbay to head the party. Gabbay is not the first Mizrahi to lead Labor, but many on the inside believed that his rags-to-riches story — born to Moroccan parents in a working-class Jerusalem neighborhood, he rose to become the CEO of Israel’s largest telecommunications company — would speak to voters in the economically depressed towns who for decades turned their back on the party.

But neither an increase in diversity nor a relatively moderate social democratic economic agenda brought Labor the redemption it yearned for. On the contrary, Gabbay’s middle-of-the-road politics, which never truly meshed with the youthful, idealistic image of some of its younger hopefuls, was a turn-off for classic Labor voters. When it came to the issue of Israel’s 52-year-old military occupation, Labor offered little: more building in the settlement blocs, pledges to evacuate outposts, and a referendum for Israeli citizens over Palestinian neighborhoods and refugee camps on the outskirts of Jerusalem. Gabbay also declared that he would not sit in a coalition with the Arab parties.

Given its lack of a clear vision, many veteran Labor and Meretz voters drifted toward Gantz — the retired IDF chief of staff who led a campaign bereft of any real promises apart from taking down Netanyahu.

Labor supporters are now blaming Gantz for his failed campaign, which they say disregarded any possibility of building a sustainable center-left bloc and siphoned off votes that would have otherwise been theirs. Appearing on a Channel 12 panel on the eve of elections, former Labor head Shelly Yechimovich looked disconsolate as the exit polls were announced, calling Labor’s poor showing a “blow to the Zionist left.”

There is indeed plenty of blame to go around for the demise of the Zionist left. But the decline of the liberal and left parties goes far beyond personalities, petty politics, or plans to replace Netanyahu. The Labor Party is still one dedicated to promoting Zionism — an ideology that privileges Jewish Israelis at the expense of all other citizens. Shifting away from Zionism would mean undermining its raison d’être. Maintaining the status quo, on the other hand, would mean compromising its very ability to put forth a real vision for change.

These elections, and the diminishing power of both Labor and Meretz in Israeli politics, show that the Zionist left’s strategy of superficial adjustments over radically overhauling its platform and agenda is backfiring. The inability of the Zionist left parties to address not only their own political shortcomings, but the very ideology that uprooted millions of Palestinians, turned them into refugees, and expropriated their land, means they will never truly transcend their built-in contradictions. As long as the Zionist left remains undecided over whether it is more terrified of forming a real alliance with Palestinians or with those who seek to disenfranchise Palestinians, they will continue to shrink into irrelevance.