It is a generally assumed that the Shah’s downfall led to the severing of ties between Israel and Iran, which up until that point resembled a love story. However, both Iran’s intellectual elite and the rest of the nation drastically changed their views of the Jewish State after 1967.

By Lior Sternfeld

The relationship between Israel and Iran dates back to the early years of the Jewish state, and constituted the basis of both countries’ geopolitical policies. This political relationship was not, however, merely a matter of the ruling elites. Insofar as Pahlavi’s Iran is concerned, even oppositional circles in the 1960s and 1970s had a complex and sometimes favorable approach to the State of Israel. Moreover, many of these viewed Israel and Iran as essentially exceptional in nature in the contemporary Middle East, a perception that would change definitively for the worse after the 1967 war.

Shortly after the establishment of Israel in 1948, a new love story began in the Middle East. In 1950, Iran granted Israel de facto recognition and opened an embassy in Jerusalem. At that time Iran was (and still is) a homeland to the largest Jewish community in the Middle East, and a safe haven for many Iraqi Jews who had fled persecution in Iraq throughout the 1940s.

Unlike the majority of Jewish communities in Arab countries, many Iranian Jews decided to stay in Iran after the establishment of Israel. While most other Jewish communities in the Muslim world vanished between 1948-1956 and migrated en masse to Israel, the vast majority of Iranian Jews stayed in their homeland and had a complex relationship with the Zionist movement and Israel. This is not to say Iranian Jews were anti-Zionist. However, due to their decision to stay in Iran, Iranian Jewish communities were generally not identified with Zionism. This was, of course, a sharp contrast to most Arab-Jewish communities from Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, Morocco, and Libya. Many Arab-Jews emigrated to the newly founded State of Israel before 1956, due of increasing tensions (and at times outright persecution) with the local populations on the background of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

In the years following Israel’s establishment, non-Jewish intellectual and political elites in Iran generally saw Israel in a positive light. Many were intrigued by early articulations of Labor Zionism, which emphasized the proletarianization of society through dominant trade unions and communal agricultural-based collectives such as the kibbutzim. Left-leaning movements, like the Socialist Union and the communist Tudeh party, were dominant domestic opposition forces in Iranian politics. Once their attitudes towards Israel are examined through a geopolitical lens, their perspectives become significant and understandable. The Soviet Union, which supported the Tudeh Party, also supported the UN Partition Plan of Palestine in 1947 (which divided the land between a future Israeli and Palestinian state) and went on to recognize Israel in May 1948.

Given the prevalence of the “Aryan Hypothesis” in Iran and the general yearning Westward during the Pahlavi dynasty, an ideological pact with Israel made a great deal of sense. This was especially true after the inception of the White Revolution in 1963, a move that was advertised as an attempt to rapidly modernize Iran along Western lines. The notion that these countries shared a more “Western” attitude even though they were situated in the “East” became an integral part in the foundation of a regional coalition among the non-Arab countries of the Greater Middle East (Turkey, Ethiopia, Iran, and Israel). This coalition came to be known as the “Alliance of the Periphery.”

The Shah, however, was a deeply unpopular and autocratic ruler among the majority of Iranians. Despite Israel’s role in consolidating the Shah’s autocratic rule, the Iranian elite’s fascination with Israel helped to create a surprisingly favorable opinion of Israel in Iran. Due to the close ties between the two governments, Iranians tended to associate Israel with projects like the rebuilding of Qazvin after the earthquake in 1962 rather than with the notoriously brutal Iranian secret police SAVAK, which the Israeli Mossad helped establish and train.

Although many of the political leaders of the Iranian Jewish communities were sympathetic to the Zionist cause, most Iranian Jews remained indifferent to it. In fact, many joined leftist movements in Iran and eventually assumed leadership positions in them, demonstrating that their political allegiances belonged first and foremost to Iran. Naturally, this situation caused major frustration in Israel, a state whose existence was and still is premised on the notion that the destinies of world Jewries and the State of Israel were inexorably intertwined.

The predominant Iranian Jewish interpretation of Zionism was different from the political Zionism espoused by the Israeli establishment at that time. The former did not necessitate the existence of a Jewish state, but rather reflected a religious sentiment and an emotional-cum-spiritual attachment to Zion, the biblical name of Jerusalem. This was not unique to the Iranian Jewry, but rather common among Jews across the Middle East. It, however, remained relevant only to Iranians, as the other communities for the most part ceased to exist post 1948-1956.

While many Iranian Jews had relatives in Israel and had visited Israel before, Israel was not part of their Jewish identity, and they did not see themselves leaving their beloved homeland for any other country — including Israel. Overwhelmingly, they did not share the political interpretation of of Zionism with the Zionist movement and Israel and tied any meaning of the term to the existence of the State of Israel.

To understand the unique place Israel occupied in the Iranian worldview, one should consider that Iranians who wrote about it. Jalal Pahlavi Al-e Ahmad, a foremost Iranian thinker, may have best conveyed the transformation of Israel’s representations in the Iranian public sphere. Al-e Ahmad, a one-time member of the Tudeh leadership, gained leftist-internationalist credentials with the publication of Gharbzadegi (1962), in which he criticized the tendency of broad segments of Iranian society to blindly mimic the West. Gharbzadegi (“Westoxification”) lamented the inevitable loss of Iranian culture and identity to Western models and paradigms. His publication influenced a later generation of Iranian revolutionaries such as Ali Shariati and the current supreme leader, Sayyed Ali Khamenei.

Given his remarkable place in both the evolution of the Iranian Left and the development of contemporary political ideologies, one would not expect that he should name Israel as a model society. Yet, Al-e Ahmad conjured ideas that were common among intellectual circles in Iran before 1967 — ideas which brought home the message that Israel in its essence was a cultural and political ally.

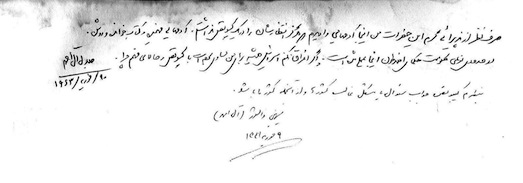

Two years after the publication of Gharbzadegi, Al-e Ahmad and his wife, Simin Daneshvar, visited Israel. Al-e Ahmad’s travelogue, Safar Beh Vilayet-e Ezrael (Journey to the State of Israel) attests to the profound impression the country left on him. The critical thinker wrote about Israel in nothing less than admiring terms. He described in details a visit to Yad Va’Shem, the Holocaust memorial museum in Jerusalem, and expressed his fascination with the resurrection of the Jewish people after the horrors of the Holocaust. Later, he broadly discussed the Kibbutz in Israel and the state’s socialist ideology in positive terms.

During their visit, Al-e Ahmad and Daneshvar stayed in Kibbutz Ayelet Ha’Shahar in northern Israel. He described the Kibbutz for the Iranian reader as follows: “[…] these people in Israel had already laid the foundation for the socialization of the means of agricultural production in a part of the world which had been inspired by the Russian Social-Democratic movement and not by Stalin.” Thus, Al-e Ahmad associated Israel with the “correct” side of communist ideology, as the contemporary rift in the Tudeh party also created another communist opposition to Stalin’s legacy.

There is perhaps another reason for Al-e Ahmad’s great sympathy for Israel. In his travelogue, Al-e Ahmad depicts the Arabs in derogatory terms as ideological and cultural enemies, to say the least. Cultural tensions between Arabs and Iranians surface clearly in the text. As he wrote: “I am a non-Arab citizen of the East who has suffered much at the hands of the Arabs and still does. In spite of all the services that ‘I’ [I as “Iran,” not the person of Jalal Al-e Ahmad] rendered to Islam through the ages and still does, they still refer to me as Ajam,” which, in this context, likely means a “foreigner” and “illiterate” as well. Similar statements can be found throughout the text. Given Al-e Ahmad’s public status, this travelogue certainly had an impact on Iranian perceptions of Israel.

Interestingly, Safar beh Vilayet-e Ezrael was published in a series of newspaper articles which was read and discussed among secular and religious intellectuals. For example, Iran’s current supreme leader, Seyyed Ali Khamenei, later recalled that this travelogue not only puzzled him but also stirred major controversy among the young clerics in Qom, specifically because of the inherent contradiction they saw between this book and Al-e Ahmad’s previous popular writings, first and foremost Gharbzadegi.

The year 1967 was a watershed moment in the relationship between Pahlavi Iran and the State of Israel. The Six Day War, during which Israel invaded its neighboring countries and occupied the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, the Sinai Peninsula and the Golan Heights, transformed Israel into a colonial power in the eyes of Iranian intellectual elites. After the war, many of the Soviet Bloc countries severed their relations with Israel, as did their satellite parties, including the Iranian Tudeh.

Jalal Al-e Ahmad wrote the last chapter of this travelogue in 1968, faithfully reflecting the transformation of Iranian attitudes towards Israel. In this chapter, he describes Israel as a part of a Western capitalist scheme in the region, explaining that the reactionary Arab regimes played into the hands of Israel and the colonial powers. He also criticizes French intellectual elites for their betrayal of the Arabs and supporting, yet again, a new colonial venture. His criticism was aimed directly at Jean-Paul Sartre and Claude Lanzmann for condemning the French colonialism in Algeria and being very critical towards Britain’s ventures, yet miraculously finding a way to ignore the exact same problems when it came to Israel.

Along with the elite’s opinion, Iranian popular perceptions of Israel also changed dramatically after 1967. A clear popular expression of this came about in 1968. That year, the Israeli and Iranian national football teams played against each other in Tehran as part of Asia Cup finals. Habib Elghanayan, a wealthy Jew and a community leader, purchased a large number of tickets for this game for Iranian Jews to attend and cheer for the Israeli team. This game, however, became a site where Iranian fans vehemently showed their discontent with Israel’s policy. The Israeli team and their supporters fell victims to brutal incitement and had to be escorted out of the stadium by the police. This incident reflected a sea change in the Iranians’ attitudes toward Israel. A one-time favorable partner now became an unwanted foreigner, protected only by the grace of the Shah’s iron fist.

Beginning in the 1970s, the Shah attempted to find new alliances in the Middle East and beyond. Iran’s relations with the Soviet Union and some of the Arab countries were revisited. A peace agreement with Iraq and the American election of President Jimmy Carter in 1976, and the subsequent harsh criticisms that Carter voiced against the human rights conditions in Iran, led the Shah to develop a more negative view of the State of Israel. By the late 1970s, the revolution toppled the Shah, and the new regime reflected the Iranian public’s feelings towards the State of Israel with vocal anti-Zionism, kicking the Israeli diplomatic mission out and developing strong ties to the Palestinian resistance. And while the majority of Iranians would come to forget the mixed feelings they initially harbored towards Israel prior to 1967, Jalal Al-e Ahmad’s writings still stand as an almost lonely testament to that time.

Lior Sternfeld is a PhD Candidate in the History Department in the University of Texas at Austin. His research focuses on Iranian social history and the religious minorities in Iran during the Pahlavi era. This post was first published on the Ajam Media Collective, an online space devoted to documenting and analyzing cultural, social, and political trends across diverse Iranian, Afghan, Central Asian, and their Diaspora communities, and was translated to Hebrew in Haokets.