The spread of the novel coronavirus continues to claim thousands of lives worldwide, putting even the most advanced healthcare systems to the test. But while the pandemic may be an equal threat to all, it is far from affecting all communities equally.

We know that vulnerable groups — families sharing tight living quarters without clean water or sanitation, laborers who have been laid off and cannot afford enough food or health insurance, communities that have been crippled by years of state violence and neglect, among many others — have been hit much worse.

With that reality in mind, we wanted to hear from people across Israel-Palestine, and those in the diaspora, on how they are personally being affected by the pandemic. This is the first installment of those stories. If you would like to submit a diary entry, contact us at oped@972mag.com.

Dejen Mengesha

April 6, 2020

TEL AVIV — I fled Eritrea and came to Israel in 2012. Today, I live in south Tel Aviv, where the pandemic has made life even more difficult for asylum seekers. The Israeli government does nothing to provide us a normal life with unemployment benefits, which Israeli citizens are entitled to. Of course, the pandemic is difficult for everyone across the world, but right now, it is especially difficult for refugees.

Some in our community are single mothers who have to take care of three or four children. It’s very difficult. People with pre-existing conditions can’t get their medication because everything is closed. We’re seeing now just how bad it’s getting, and it will certainly get worse if the government doesn’t intervene.

I live by myself and I thank God that I’m young. But all around me are older asylum seekers in their 70s and 80s who are having a very difficult time. They aren’t able to pay their rent. If they don’t find a solution after Passover, we’re going to see people being thrown out into the street by their landlords. They will have a hard time making it past the end of this week. God help me, it’s so hard to watch.

The younger asylum seekers are trying to speak to landlords to convince them to allow people to remain in their homes for a month or two. Most of the landlords refuse to listen to us. Of course, this situation is hard on the landlord as well — I understand that. But there is a solution: they should ask the government to support them. Don’t place this burden on us.

I wake up every morning worried sick. I work and volunteer as a translator at a health clinic in south Tel Aviv, near the old central bus station. Everyone who comes in is in hysteria, and our clinic doesn’t test for COVID-19. Every day I see people in the most difficult situations coming by the dozen to get checked. All I see is people under stress, who are facing serious economic challenges. But beyond the financial troubles, I’m worried that all of this will leave a psychological scar for many.

Dejen Mengesha’s entry was delivered over the phone.

Mohammed Moussa

April 3, 2020

GAZA — As a Gazan, my life under quarantine isn’t all too dissimilar from my daily routine before the pandemic. This is what life under siege looks like. This is how Gazans have spent the last 13 years.

I keep going back to my memories of the 2014 war, when I used to spend most of my time at home, doing nothing but listen to the radio to keep up with what was happening. The streets were empty and Gaza looked like a ghost town.

During that war, I spent 52 days at home in self-isolation — not from the coronavirus, but from war. As a Gazan, the feeling is not new to me. But this is a global pandemic, something completely different. Something I have never experienced, and which has taken the lives of tens of thousands of people across the world.

There are currently 12 cases of COVID-19 in Gaza. Like everyone else in the strip, I was afraid the coronavirus would enter through our border crossings with Egypt or Israel. Egypt currently has 1,170 declared cases and 78 deaths, while Israel has more than 8,600 cases and 51 deaths.

As I write, I can hear children playing soccer barefoot in the alleyways, the sounds of bicycles and cars on the street. A group of men walk by with no masks or gloves. A man rides a horse.

Sometimes I feel like people in Gaza are underestimating the coronavirus. Or perhaps they’re not. Maybe they’re not sure if they can do anything at this moment or whether they can even survive it. They keep saying, “If the U.S. or U.K. didn’t survive this, Gaza cannot.”

Opinions differ on COVID-19 in Gaza. But panic is growing, and what may come soon is frightening everyone. This ugly virus can spread here so quickly, that even one infection in a dense place like Jabaliya Refugee Camp could lead to a catastrophe on the scale of what we’re witnessing in Italy, Spain, and the U.S. This is why the authorities closed the crossings and the mosques, and suspended schools and universities.

I didn’t wear gloves or a mask when I went to the supermarket earlier today. I only had hand sanitizer in my pocket, which I used constantly.

I was relieved when I found the cashier wearing black gloves. But in the street, people are still hugging each other, walking close to one another, and sharing food. There is no social distancing here; perhaps people don’t know what it means.

The coffee is boiling, the television is blaring in the background. The news talks about a surge of deaths in America, the new epicenter of the virus. Is it going to end this summer? Will it last? Will the world be the same?

I try to disconnect from social media and the news, instead finding myself watching movies online, even ones I used to dislike. These are strange times.

Today after lunch, I FaceTimed with a friend, a poet living in the U.K. “I’m pretty isolated up here,” she said, “but I’m part of a caring community that’s finding ways to keep in touch and support each other. It’s very odd to be under curfew, and the whole process of getting food is very strange.”

I shared with her a poem I wrote yesterday. It has been a while since I wrote something to help her feel better:

“Featherless Bird”

An empty tall wall

Behind me

An empty cup of tea

Next to me

Featherless bird

Inside me

And a picture of her face

In front of me

Doesn’t leave me

Fills me

Revives me

Now, it’s 7 p.m. I’ll go for a walk after I drink my third cup of coffee.

Mohammed Moussa is a freelance journalist based in Gaza, and the founder of Gaza Poets Society, a platform for young and aspiring poets in Gaza.

Saleh Diab (Abu Anas)

April 1, 2020

SHEIKH JARRAH, JERUSALEM — There is nothing harder than the occupation. Coronavirus will pass, but the occupation has been here for more than 100 years. I have been protesting against the Israeli occupation every Friday for the past 10 years. I believe in my cause.

Many Palestinians in Jerusalem are cut off from essential services, including medical care. We have nobody looking out for us. Do you know how many families are in need? Do you know how many workers go to work in Israel? If they lose work for a single day, they will have nothing to feed their families.

I have been living in quarantine in a separate home, away from my wife and children, to protect my family. I work at a supermarket, and I don’t know who I’m dealing with, who the clients are. I buy groceries for my elderly parents and leave the bags outside their door. I’m worried about them, not myself.

The separation reminds me of the years I spent as a political prisoner. I’ve been imprisoned 13 times. Today, I speak to my family only on the phone, and it makes me feel like I’m in prison again. I’m thinking of the prisoners and pray for God to be by their side. I speak to my family daily, every hour. What can we say about the prisoners who have been locked up for more than 25 years?

But I am hopeful. Nothing is impossible. I have faith that we will persevere.

Saleh Diab’s entry was delivered over the phone.

Mary Hazboun

March 30, 2020

CHICAGO, ILLINOIS — This quarantine is not a yoga retreat.

You see, I wish I had the capacity to sit still. But it’s a privilege I do not possess. To allow myself to feel my body, all of it, and to be at home with it.

You see, my body has gone through military occupation, displacement, and sexual violence. These experiences are stacked on top of each other and suppressed in this body. The emotions from these experiences are also buried deep down, together with the actual events that caused them.

People like myself were never taught how to process these experiences, nor did we learn how to safely absorb the feelings they created. We modeled our responses according to people around us, who either dismissed these experiences or told us to move on. As a result, we have gone through life as if these events never occurred. It’s not our fault.

This quarantine is not a yoga retreat. Not for people like me.

My body is a house that holds a lot of damage. Yet its foundation is resilient because it is rooted in Palestine. This is how I keep going.

In this era of COVID-19, I still can’t decide which is worse: the virus itself, or being forced to sit still. You see, throughout my life until two weeks ago, my coping mechanism, like many diasporic Palestinians, has been to stay in an endless “flight response.” I was always on the go. I’m obsessed with staying in motion so as not to be still with my body, because I don’t have the psychological capacity to sit with the weight it carries for long periods of time.

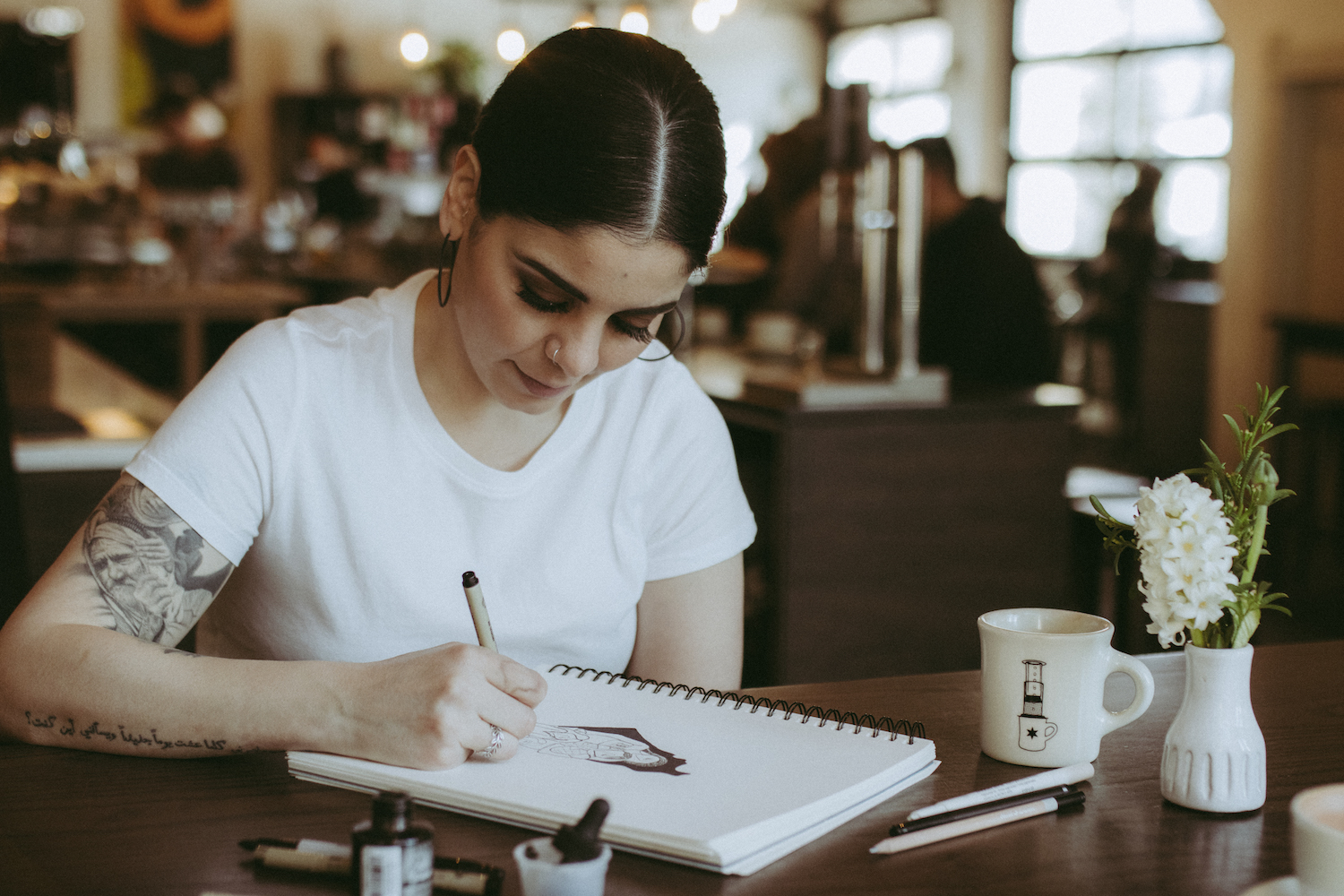

I’m doing healing work, but at my own pace. I used to work 90 percent of the time, and sit still 10 percent of the time. I used to work and workout five days a week, and deep clean the house three days a week. My evenings were the only time I allowed myself to unwind by drawing my longing, my diaspora, and my fears into my sketchbook as I sipped my black tea, smoked my apple-flavored hookah, and listened to Um Kulthoum.

Creating art has been my way to cope, because I’m often unable to use language to tell my stories. When I began drawing, it was my body’s way of creating a space to grieve, and that’s why I named my collection “The Art of Weeping.”

Since I was forced to leave my homeland in 2004, I’ve felt like I’ve gone through a sudden death. Everything I knew of home came to an end: my house, my friends, my cousins, my grandparents, the streets of Bethlehem, the Nativity Church, my school, my dad’s grocery store, and my grandma’s afternoon coffee… As a Palestinian artist in the diaspora, I continue to cultivate radical hope through the memories I carry.

Mary Hazboun is a Palestinian artist and public speaker on Palestine, anti-colonial feminism, trauma, gender justice, and activism. Follow her on Instagram: @maryhazboun48.